This is Barbara London Calling. Welcome once again to my podcast series about the wild world of media art. I’m calling media artists from around the world, many of whom I’ve worked with as an author and curator. Together we’re exploring what motivates and inspires these artists, and how they see the world as media artists working at the forefront of technology and creativity.

Today, I’m calling Zina Saro-Wiwa, an interdisciplinary artist whose mediums include video, photography, sculpture, sound, and sometimes food. Zina has said as an artist, she wants to free herself from super colonized ideas about her native Nigeria, while expanding what it is to be an activist and environmentalist.

She wants to broaden the meaning of Africanness and ultimately decolonize the idea of self. Born in 1976 in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Zina grew up in the UK and currently lives in Los Angeles, where she brought with her a love for Nollywood movies from Nigeria’s fertile film industry. Zina, thank you for joining me.

ZINA SARO-WIWA. Thank you for having me, Barbara.

Transcript

BL. There’s so much to discuss because you have such a rich career. Let’s start at the beginning. You were born in Nigeria, studied economic and social history at the University of Bristol in the UK. And you spent a gap year on the Atlantic coast in the old Brazilian capital of Salvador. Tell me what was it like in what might be called these formative years of your life?

ZS-W. Well, first of all, growing up in a very white English suburb in England was one thing, then also having a very Nigerian family was another. There was always this real cultural leap that had to be made. I went to a boarding school that I loved and I had a wonderful time there. That was really good in grounding me, I think. I have a twin sister, as well. I feel the experiences at school were wonderful. It grounded us in that space. Then things started to unravel when people started dying in my family. I think that’s when my journey as an artist began, even though I didn’t realize it. My little brother died in ’93, then my father was killed in ’95.

In a way that changed a lot of things in me, and it set my life in courses that I wasn’t imagining. I had this idea that I would go to a different university. Life went very differently. Also, this other seed of Brazil had been planted in me, as well. This is another strand of my being that God implanted. I think it was implanted before I was born, but certainly implanted cognitively at that age. The death stuff made me think about the other side of life, where do these people go when they die? In Brazil in Bahia, Salvador, I was exposed to a spirituality, even though I was very Nigerian, in a sense. We went to Nigeria every holiday and we knew where we were from.

I know the village I’m from. Not many Africans in the diaspora can say that, but as a Nigerian, I have a village that I’m from and know exactly where I’m from. I think what happened was that in Brazil, I found something. There’s some sort of spirituality that claimed me, I didn’t claim it. I didn’t know anything about it. It claimed to me. There’s that strand. Then there’s a side of me that’s very, very traditional and almost conservative, I would say. I studied economic and social history. I’ve always loved learning about Germany and Japan, which were my passions. I loved World War II. I can’t tell you why. I never loved Russia as much. I remember learning about the Irish question that didn’t interest me so much.

But the Industrial Evolution was really what I studied. That has always interested me, too. I think that undergirds so much of our lives today, in a sense understanding how economies have developed. I have to say I have never studied African economies, I never studied colonialism, nothing like that. It was always European, but that hasn’t stopped me doing my own private research and having my own interest in our own ways of thinking about history and the way that our lives in Nigeria, and as black people in the world have gone forward. I’ve always had this crazy interest in the Second World War and in economic history.

I’ve got all these different strands. I’ve got the Brazilian spiritual strand, and I’ve got this other, different strand where I’m interested in industrial history. I think those two things set the scene for something very different. Then I was also a journalist, I suppose. I worked at the BBC. I did many different kinds of things. I was a researcher; I started out as a presenter, actually, a reporter, researcher, producer, I did everything on radio and then ultimately television. It was cooking something interesting in the pot. I think my mother might have wanted me to become a more fully fledged television presenter, but I knew I didn’t want to do that. I couldn’t, I wasn’t happy in that role. Then art claimed me.

BL. At the BBC, you were doing also cultural programming, were you? You were interviewing, talking with subjects, coming up with topics and ideas.

ZS-W. One of my favorite shows that I worked on was called “The Long View,” which is great… It’s about an issue that’s currently in the news and the show looks at similar moments in history. And looking at the connections between what happened then and what’s happening. At the time, I was doing something about the rise of China, and this idea that China is going to take over the world. And understand this has happened two or three times before in history, where the West has had this idea that China is going to rise and take over the global economy.

We had to look at that time, find readings around that time, and then we had actors perform these readings at the relevant different sites. It was a wonderful show. Very inventive. I ended up in culture, but before that it could have been absolutely anything else. I worked on a show called “You and Yours,” which is a consumer rights show. I worked on “Woman’s Hour,” which could have been literally anything under the sun, as long as it pertained to women’s issues. I’ve worked on “All in The Mind,” which is a mental health show. All sorts of things, everything.

BL. I think you stayed at the BBC ten years. How did that experience help to hone or sharpen the way you tell a story in your own art practice?

ZS-W: Well, I’ve never really had a job. I was freelance and I’ve always been freelance, but yes, I was there on and off for about that time. And actually, I got myself work experience at the age of 14 there, as well. I was fully obsessed from a very young age with Radio 4, which is a BBC talk radio station, which is wonderful and I think is responsible for undergirding British democracy, and I think America could certainly do with a radio station like that. It’s like all the best podcasts in one place. What did it do? I’m really grateful for the way that it expands your sense of what the world is. I think that also, and the research is this thing.

I’m very big on researching, and that was actually my favorite job, not the reporting side. Actually the researching side was my favorite bit of my job. I really realized the devil’s always in the details. You’ve got to do the work, you’ve got to do the research, and that’s what that partly taught me. But I felt constricted by this idea of time. In television and radio, it’s like time is of the essence. The format is sometimes more important than the idea and that ended up pissing me off anyway, which is why I left. This idea of having to craft a narrative to fit a particular time slot. You had to be efficient. I’m super-efficient now in the way that I make work and the way that I create it.

I can pull things off in the way that I would have to if I was a researcher [on a radio show]. You have to research the Battle of Culloden and come up with some speakers that can talk about X, Y, Z and come up with a structure and you need to do that in a week, so I can go off and do that. You can give me anything and I can… I’ve always been able to do that, but the BBC certainly forced me to do that over and over again, so I grew and I learnt. I never went to college to learn any of this stuff. I didn’t even do any of the BBC courses. I just did it, and that’s really been my entire career, just doing the work, not really studying, just doing it and learning on the job.

I would say the importance of research and devil in the detail, but also sound is so important. I’ve always been a musician, I’ve always sung in choirs, and then when I left school, I was doing more Brazilian music. I’m a songwriter, and I do Brazilian style. Music and sound are always so important to me, and I think when you’re working in radio, you’re just working with sound. You’re just sitting there with your earphones on and I’m old enough that when we were cutting radio, we were cutting it with razor blades, we were cutting the actual tape with razor blades. That was right at the end of my time, but I was there very, very young and so I was doing that kind of work then.

That was extraordinary, really. You’re learning about experiencing the world through sound and what you can do through sound, and actually, sound is more important than vision even if you’re making a film. What is more important is sound… If the vision is fucked up, it doesn’t matter, but if the sound is fucked up, then you can’t watch it. It’s unwatchable. Sound is actually far more important. That’s another thing that radio taught me. Then when I was in TV, I was a TV presenter, I was in front of the camera, and I actually found it very frustrating.

My boss at the time called me a frustrated researcher! Which is funny because everyone wanted to be a TV presenter or whatever. But I always wanted to be doing the research and I was really uncomfortable in front of the camera. Towards the end I got panic attacks, seeing myself I couldn’t cope. I didn’t enjoy being on TV that much. I actually loved being with the camera guys and the film guys and the sound guys, they were just the best. We used to just laugh all the time. I had a great time, actually out shooting and being in the world.

I think the being out in the world and learning how to craft something is important, but efficiently; the efficiency is the thing that I think I took away from that. But also, the breadth of subject matter that I was able to indulge in in those ten years it’s just a gift.

BL. Let’s segue a little bit. I gather you turned to filmmaking in 2002. Is that correct?

ZS-W. Everything’s all mixed up. I was doing radio, and like I said, I didn’t have a job job, I was just freelancing. Then I would always end up turning to film somehow. Film was always there. I always thought maybe I’m just a radio person. But that wasn’t the case, because I’d always turn away and have to attend to a different idea through film, and often it was an Africa based idea in my BBC life. I was never pigeon holed, actually, I never worked at any black radio station or anything like that. I was just always just out there in the world doing whatever ,and I preferred that, to be honest with you.

That wasn’t because I wasn’t interested in my own culture. Because that is my culture too, whatever I was making shows about or researching or producing. That was my subject matter, too. I’m a citizen of the UK as well; all of it interested me. However, when it comes to stuff about Nigerian identity and certain forms of blackness, I wanted to do it on my own, because that wasn’t my work and I wasn’t working at the kind of station where they were taking up those ideas and I wasn’t being given that kind of work, frankly. I was just doing Battle of Culloden, godless moralities, all sorts of other things, anything else.

But there’s this thing that’s missing there in the UK. And yes, I’m fairly privileged in some ways and in the world, but then I’m thinking about my people. I’m thinking about my blackness at the same time, and it’s just how I need to attend to it. That’s why I made, in 2002 I think it was, Hello, Nigeria. I think that’s the first time I made a documentary about “Hello! Magazine,” a celebrity magazine. It’s very glossy, and at the time there wasn’t anything like that in Africa necessarily. This Nigerian guy who’s in the UK set up a Nigerian “Hello Magazine” called “Ovation.” And Nigerians, ordinary people, not even famous people, would pay to be in it, and pay to have their little spreads.

Absolutely amazing. It was really about how Nigerians are seriously maligned people. People think that we’re awful for whatever reason, and it’s like this is about Nigerians celebrating themselves. I thought that was a great vehicle to discuss this idea of how we’re seen in the world and how we’re trying to control our storytelling. Actually, it’s so weird because I’ve been thinking so much about storytelling and how I want to write a book about this ultimately, or do another film about this because I think storytelling has been my obsession throughout my career, and how storytelling can fail us or how storytelling can expand our opportunities.

BL. I saw your Mourning Class: Nollywood, which is a set of video performances that explore the mourning rituals and address the role of performance in grieving. But there’s very much a sense of humor in there. I’d love to have you tell me a little more about this dichotomy of mourning and humor.

ZS-W. I’m a Nigerian and we laugh in the face of tragedy. My father had always said this, and it’s absolutely true. My family has been through horrific tragedies and we still come together and laugh. I Instagram my sister every day, sharing outrageous memes and laughing our heads off all the time, and I will do that till the day I die. It’s the only way that I know to survive. That’s a Nigerian thing I would say for sure, but also this idea of grieving and humor. It’s interesting. There are so many funny intersections of this. First of all, I’ll start with saying that in China, China has the wildest grieving kind of culture, I would say.

They have strippers at funerals, they have comedians at funerals. It’s like “Check it out.” It’s brilliant. It’s really, really interesting, how they metabolize and express death in their culture, I love it. I think it’s very, very interesting. I was looking for a way of dealing with it because these two deaths happened and one was very sudden and was very odd. It was the first death in the family; we didn’t know how to manage it. Then my father was killed in this horrific way, and then his death was managed and taken over by politics and political actors, in a sense, and by activists. I felt there was no space for me and no space for grieving within it. I didn’t cry for 10 years.

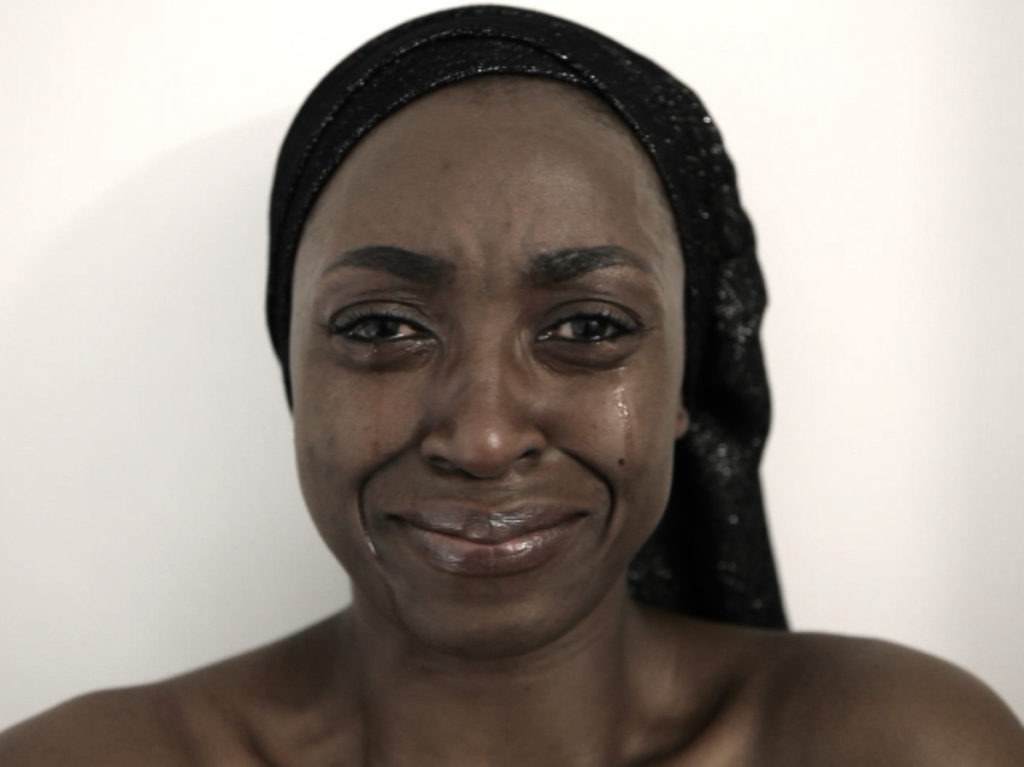

I’ve famously said in many interviews about the fact I didn’t cry for ten years after my father was killed. I didn’t know how to grieve or where I fit into this whole circus that was around him. There’s tears in a lot of my work, in Mourning Class: Nollywood, and subsequently Mourning Class that I did. Actually, it’s in my writing as well. I wrote a short story all about a girl who couldn’t cry and then she suddenly had a breakthrough, a crying breakthrough. That’s what the whole story is about. It’s called His Eyes Were Shining Like A Child. Tears and grief are always this thing that I’m trying to understand, the choreography of this. And two more intersections.

I remember one time something quite terrible was happening at home, having to do with another brother of mine [he was very upset and yelling upsets me too] and I was in the bathroom looking in the mirror and I was crying. Then I remember stopping crying and thinking, wouldn’t it be funny if I smiled right now and I just stopped crying. I smiled briefly and then I kept on crying again, which might mean that I’m bipolar. I don’t mean to joke about that because it could have been a possibility (turns out I’m not) but the fact that at that age, it was a form of trying to control emotions and trying not to let grief or fear take over you. I forced myself to cry in the middle of it and break it.

I was disassociating from the moment, I think, that’s what that was about as well. So again, laughter and tears and then another interjection, the final one I mentioned is there’s no decent way of telling it. You’ll just think me and my sister are horrific human beings, but it was having hysterics at a funeral and I can’t talk much more about that. Anyway, tears and tears and… I think with Nollywood though, I think the Mourning Class: Nollywood film was also because these actresses and I wanted to highlight the fact that it was a performance and I think I was referring to that moment where I broke the crying by forcing myself to smile. I think I am mirroring that situation I did when I was eight or nine years old.

That came into it. Also, when you’re watching someone cry in that way, everyone that watches Morning Class: Nollywood starts crying. I still cry when I watch it, I can’t cope. I’m just like, “Oh my God, I’m a mess.” You’re a mess when you’re watching it. In a way, [the smile] is just the support and comfort at the end, the smile at the end breaks it. I don’t ever want to make work that tears things apart. I hate this phrase. “I want to complicate X, Y, Z.” I’m not trying to complicate anything. It might seem more complex by the end of it, but I’m not trying to complicate it. I’m also not trying to destroy you. I want to put people back together. That’s what I care about.

Sometimes you have to pull things apart and it might be uncomfortable, but then you put things back together. My work for me is active healing. Healing is all for me. It might seem like it’s distressing at some point, but then it’s about coming back together. I think the smile at the end does that.

BL. I want you to explain a tiny bit about Nollywood, which is a form of Nigerian cinema. I read that you were introduced to Nollywood by your hairdresser in London. In that same article, there was also a quote that Nollywood prepared you for the aesthetics of the American artists such as Kalup Linzy, and Ryan Trecartin.

ZS-W. I knew nothing about art for a long time. I didn’t get into art until my thirties. Honestly, I didn’t know anything, but I would say the thing that really inspired me to make art or to get into art was Nollywood. It was Nollywood. Whenever I watch a Nollywood film, I just see it as video art; I can’t see it as anything else. It’s so abnormative. I can’t really approach it any other way. I just think this is art. I can’t think of it in any other way. In all its abnormativity. Nollywood I think is the second largest film industry in the world after Bollywood. It started in the eighties, and actually quite a lot of Nollywood filmmakers were inspired by my father.

My father did a TV show called “Basi and Company” when there was still the Nigerian Television, the national network of Nigerian television, before everything collapsed under the military regime. His show was one of the most watched shows in Nigeria and Africa. “Basi and Company” was a sitcom about a man who was trying to always make a million bucks, and was a satire on the Nigerian craving for quick cash. Nollywood, in a sense, after the collapse of television, was a way for producers to still make films but it, as I describe it, was forced into the jungle, and it ran wild, metastasized into this other form, this different kind of art form in a way.

It’s like schlocky soap opera, but it’s like so much more than this; there’s so much more going on within it. This is an engine telling our stories and our narratives. And they’re often very conservative in terms of the ideas about women, the ideas about morality, etc. I think it’s still like that and there’s a lot about the spirit world in there, and spirituality and Christianity. There’s a lot going on. They’re very, very, very, very, very funny, often inadvertently, but also on purpose. It’s brilliant. It’s so rich, but it also caused a chaos inside of me. I just didn’t know really how to deal with it and yeah, that’s how it’d be introduced.

It was always going to be somewhere in Nigeria. There weren’t cinemas at the time, there still aren’t [a lot]. I know that people are trying to create cinemas, but Nollywood isn’t cinema. It’s for the small screen or for the flat screen, that’s what it’s about, and it’s made with very little money. The budgets aren’t huge. I know people are trying to make bigger films now. But I just think that with Nollywood, there’s something very close to ourselves within it. There’s something that I can read about Nigerian-ness within it as a genre, and there’s a lot of information in there. I was really excited by it because it’s very, very chaotic, very chaotic and very problematic. And I like that, I like the problematic.

I’m someone who watches 1950s movies, the more racist the better. I love the sexist, racist, hilarious fifties American movies. I don’t know why. Something’s very wrong with me. I enjoy watching that shit. It just makes me laugh. It’s deeply problematic, but it just makes me laugh. Same with Nollywood. Nollywood is so problematic in so many ways. You’re just like, “Oh my God.” Again, it fills you with a kind of energy and I want to do something about it. I say this stuff makes me laugh. I don’t think it’s ultimately funny, I don’t think it’s correct that these things are happening. I think in my work, I attempt the correction but I really enjoy watching it because it fills me up with a kind of energy.

Nollywood is chaotic and it’s insane. TikTok is like this now, as well. People making their own videos at home, and that whole thing of straight to camera. There’s a show in England called Peep Show, which is like this, too and I think Kalup did this too. Looking into the camera, different characters looking straight down the barrel of the lens, and then cutting that way because that’s the only way that you can make a film by yourself. I just think this kind of DIY approach is encouraged in Nollywood. But you see that in Kalup Linzy and Ryan Trecartin, and I love Ryan Trecartin also because his work is about rhythm.

I could literally sit there and watch it for eight hours straight because of the rhythm. He understands that. What I hate in art film is when they’re being experimental, but they try to break out of anything that’s human and atavistic in that sense. They’ll extend a scene for way too long for no good reason. I don’t know why they would do it. Maybe they have some great reasons. I would love to hear it, but I hate that shit. I think you can be experimental but still conform to rhythm and do something; keep people with you and not piss people off. I want people to come into a video installation and stay there. Most people can’t be bothered. They go in there, they’re just like, “Okay.” And they walk out.

That’s a failure as far as I’m concerned. Then some people might think, “That’s wonderful. It’s just too big for them. It’s too important for them.” I’m just like, “You’re a failure. I’m sorry.” And I failed if I haven’t kept you. I feel like I’m a failure, if my video doesn’t keep you. I want to keep you there and I want you to sit there and watch this thing and you don’t understand why you’re watching it. That’s what Ryan Trecartin does. His stuff is chaotic and crazy, and of course, I have an appetite for this. I enjoy this kind of stuff. It’s also the rhythm and the way that he cuts and cuts and cuts and cuts and keeps you there. I’m just like, “This is delicious. This is delicious, and this is what I want.”

That’s what I want out of art film, actually. There’s a way of being experimental but keeping people drawn in and that’s what I care about. How am I going to do things that are genuinely challenging? Not just performatively challenging. Actually challenging. I’m not just speaking to the art world, I don’t give a shit about the art world. I care about what people think. I want them to care. I want real viewers to care. How do we do that? I think it’s so weird. I do think like things like TikTok and all the other iterations before this, Vine, etc., have prepared people for video art. I think that people are now focusing on tiny details or weird little moments and vignettes…

It’s lovely. It’s glorious. That’s why I spend way too much time on my phone. The last message I got was so scary in terms of the number of hours. It tells you how long you’ve been on your phone. I’m just like, “Oh my God. I can never reveal this to another human soul.” The reason is, for me, it’s almost research in my video. Honestly, I do think that there’s a relationship growing there. I just think that going forward, we’re going to get much better at video art because of Vine, TikTok and memes, quite frankly.

BL. When you moved to New York, I think in 2009, it sounds like you had a fresh start. You’ve said that America has been very good for you career wise, and that you felt like you were confirmed as an artist. I’d love to know what kind of doors opened and how being an artist in New York or in the US gave you permission to turn your back on the notions of the moral journalistic approach to storytelling.

ZS-W. That’s a great question. I think a fresh start for me meant New York, but maybe if I’d grown up in New York, a fresh start might have meant going to London, but in my case, it was leaving London behind and coming to New York. I had no idea what the plan was. All I knew is that I just had to get out of England and start again. What had happened is I’d made a film called This Is My Africa and we were over in New York the summer, because there was supposed to be a big trial with Shell Oil, about the murder of my father and eight other people in 1995. I had decided before that I’d wanted to make a documentary about my father, and I decided to link up with a friend of mine.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

We thought, “This might be a great moment to film.” We went to go and film what we thought was going to be the trial, and we’re trying to sell the doc to HBO. I went over to HBO offices, had a meeting, and I didn’t have a card, but I did have this DVD, which had my email on it. I just gave them the DVD, not thinking anyone would watch it. Then two weeks later, I was back in the UK, and they called me up to say that, “We watched your DVD.” I’m like, “Okay. Really?” Then they said, “We want to license this film.” As opposed to the one about my dad. I was like, “Okay.” I literally had to stop myself from telling them no, you don’t want that because I’m really good at self-sabotaging.

I had to cover my mouth and nod and be like, “Mm-hmm. Thank you.” Then by the time I moved over to New York, that was my job in the beginning, clearing the rights to the film. Then also, I was working at BBC at a place called “The Culture Show” and one of our interns at the time, he was just there briefly, but he made a big impact on me. He ended up working at Victoria Miro gallery and then moved over to Pace in New York. And he said to me, “Darling, you’ve got to come over. You’ve got to come over and do some stuff. Something with the gallery that I’m on the board with, you must.”

I came over and after I did the HBO thing, I started to work on Sharon Stone in Abuja, which is the exhibition about Nollywood. It was weird because I was offered a solo show. I’ve never been an artist before, and Location One offered me a solo show. I was like, “No, I think I’ll invite other artists on board [to join me].” I had Pieter Hugo, I had Wangechi Mutu, I had an installation with Mickalene Thomas and work by Andrew Esiebo. I realized that the reason I was able to just come up with this and not really have any fear wasn’t just beginner’s luck.

It was also the fact that I’d wrangled with and ended up writing a massive essay for [photographer] Pieter Hugo’s monograph about Nollywood. I’d wanted to write something that was very straightforward that gave you the story from beginning, middle and end, just to locate it in some factual reality. That established my cognitive relationship with the genre. What it also did is that it isolated the things that I couldn’t quite articulate. I always think of ideas, stories, things as physical beings. As a physical being the story of Nollywood was really hard to grapple with. I was online, I remember writing to people, “This is eating me alive. It’s taking over.”

When you read the essay, it feels like a very straightforward text, but I struggled with this one. It was very, very bizarrely hard and when that happens, it’s because it’s bigger than it is. It’s a bigger deal than I realized. It’s actually a bigger entity than that. It wasn’t just this essay; it was actually the spine of my entire career. It was the beginning. I didn’t know that at the time, but what it did, writing that essay, established my cognitive relationship [with Nollywood] but also exposed the areas that were still messing with my mind and making me crazy and not knowing, “Well, how do I deal with this?” And text wasn’t going to deal with it, but art was. I had all these ideas as a result of writing the essay, and that’s why it was easy for me to curate the show and say this is what I want. To say I want to look at the conventions, the visual conventions of Nollywood and just play with them and explore them.

BL. We’ll move on a little bit to around 2013. In late 2013, you gave up your Brooklyn apartment. When you gave up the lease, you already had a connection with The Menil Collection. You had done a couple of works for them and you had a commitment from the Blaffer Museum for a show, and I absolutely adore your title. The title is, “Did You Know We Taught Them How to Dance?” You left for Nigeria with the show as a possibility, and then you did several things. You launched the Boys’ Quarters Project Space in Port Harcourt, which you opened in your father’s old office. Your father, Ken Saro-Wiwa, was a noted environmental activist in Nigeria. Tell me more about this project in your father’s old office and how it came about.

ZS-W. Leaving New York, I had a nice round of shows. I did something at the Pulitzer Foundation and at The Menil. It was the same show, but I made a lot of work for both those shows. That was really exciting to be showing at the Pulitzer in St. Louis showing alongside Sophie Calle and Yinka Shonibare. That was a really lovely show to be able to be a part of. The Menil was another really great show. Then I got bored off the back of that. I got bored quite a lot in New York. It’s the weirdest thing. I just didn’t feel it energetically. And there’s a lot going on, but I don’t know that it necessarily matches with my energy and I just got bored and I thought it’s time to get back to Nigeria.

I asked God, “I want this, this, this, what should I do?” And the answer came immediately, “Go to Nigeria.” I was like, “Okay.” So, I did, and I talked with the Blaffer Museum staff about a show, but at the time I didn’t know what. I was speaking to people, I wanted to raise money for what I was doing. I didn’t have any money. At the Blaffer was the amazing [curator] Amy Powell. I’d been in contact with her in Texas, and I was just telling her about my idea and she said, well, I could do a show… Again, another opportunity handed to me on a plate. I feel very fortunate for that.

I went to Nigeria not knowing what the show would contain, but knowing that I had that commitment. I had no money there still. I just went over there and I think Boys’ Quarters Project Space came about because I thought that I wanted to do work on the street, as well to make actual artworks there. Articulations on the street. It was crazy. No one gives a shit about your little art vomit on the street in Port Harcourt. Actually, a far more radical thing to do is to create a white space so that people can get away from the bedlam and the noise on the street and have a space to engage with art in peace, and that doesn’t have any transactional activity around it.

That’s where that came from. Originally, the project was supposed to be in the Boys’ Quarters, which is the servants’ quarters. That’s a very politically incorrect name that we have for the servants’ quarters and I originally was going to do it in our house, but then my family made it clear that I shouldn’t do that because we can’t invite strangers onto the property. So, I had it in my dad’s office and I kept the name. I’m committed to showing all kinds of art, but video has also always been very prominent. It’s not that it’s easy. I always think it’s easier to show a video show. It never is. It’s never as easy as I would love it to be. You obviously know this.

Video shows are so hard, but in Nigeria with the lack of electricity and the sounds of the generators, it’s really, really hard. But video was always there, because in my dad’s actual office, what I call the Windowwall Gallery, I covered the window that he would have looked out of, and we projected videos onto there. No matter what the show we were doing, there was always a video element in it. Then often we’ll do actual videos in the space. Video is a big part of the Boys’ Quarters experience for sure.

BL. I can only imagine how important it was for all of the people there in Port Harcourt. You created not only your own amazing work. I think the photo series and a five channel installation called the Karikpo Pipeline that you made in Ogoniland, which is the region of 111 villages in the five kingdoms of the Niger Delta in South Eastern Nigeria, whose art is rooted in ancient beliefs. I think it’s quite amazing how you did it. You sent a drone over the landscape, which you used to photograph from above the endless vistas of lush green land, but underneath that is a track of buried oil pipeline.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

I love how you have this troupe of masqueraders leaping and tumbling, wearing their antelope masks. The antelope mask is your icon, which I think is really beautiful, in its abstraction. The icon is on the cover of your recent catalog. What is the statement you were making with the Karikpo Pipeline series of work?

ZS-W. The Karikpo Pipeline, as you perfectly describe it, is really about the idea of who owns the land, who gets to describe the land. We have a road that I take every time I go to Ogoniland from the city of Port Harcourt. Driving to the rural area of Ogoniland, you have to go down a big road called Refinery Road. It reminds you of the colonial powers within Nigeria. Not so much in places like Kenya but in and within Nigeria they did colonize us but it was more about extracting resources. They weren’t really interested in settling, which is probably better for us in some ways, because it’s not their kind of climate. They would like in Kenya, which is a better climate for Europeans perhaps, I don’t know.

It was about extraction purely. We have a road called Refinery Road, and it just reduces us to what we can provide for the world in a sense, and I can’t stand that. That was always the beginning of that kind of conversation, which would really annoy me. Then, also just not being able to go down certain roads, or feeling that, this is my ancestral home, and I can’t go certain places.

There’s an interesting cartography that has claimed that space. I was moving into that territory, not as someone who wants to think about or work or reflect the trauma that happened because of oil. I wasn’t there looking for those kinds of stories. I was there looking for culture. These masquerades represent that culture for me, and for me, it was about pitting that narrative against the other narrative, the oil narrative. So it’s a conversation between those two narratives and asking which is more important.

BL. They’re a very powerful series. I also was quite moved by your video series called Table Manners. For me, that was so mesmerizing because these individuals are eating, just simply eating, and I guess you call it an eating performance for your camera. The viewer is able to sit down and enjoy the meal, as each of these diners were smacking their lips, just loving what they were doing. I’ve also read that you said the work is less about food, and more about showcasing the soul. I really love that. I’d love to hear you talk about it because each video in the series has a beautiful backdrop, the very colorful fabric and the table setting.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

ZS-W. I thought you were going to say it’s about place because that’s what I normally say. It’s not about eating style, it’s not even necessarily about colonialism. I just put that title there because it was provocative, but it’s about place to me, but inadvertently what ends up happening is that you do end up showcasing the soul. It’s a different performance. Something is happening in elemental energy that is transmitted when you’re eating with someone. It’s a powerful thing and people are discomforted by watching some of these performances. Some people can’t watch them. Some people are mesmerized by them. Some people are repelled by them. It’s very interesting, the effect it has on people.

It does absolutely showcase the soul, but it’s also about place. Everything is local, everything is a document of the moment at the time that it’s constructed. Again, that leap between that space between reality and performance that I’m very interested in, which is also quite Nollywood. Nollywood is always shot in people’s homes which I love. It’s ingesting and making work about and layering information on top of what is reality but also constructed reality because these people’s homes are these things that people are trying to create an identity with. I think with Table Manners, I’m drawing from the natural surroundings to construct a set. It is a set because it is a performance.

BL. Each one of the people, they are indeed performing and looking straight at the camera, but most importantly to me is they appear to really trust you, and they really enjoy it, and they really seem to take their role seriously. Were they collaborating with you?

ZS-W. I don’t know what you mean by the word collaborate, as such. I had to direct them, and it’s not an easy film to make because for every one that you do, especially in the second season that I made, there are four [performances] that I couldn’t use. I’d have to run this over again four or five times with different people. It’s really hard because I wanted to show people. I did a talk and I think I showed them one where it failed, because just to get in front of a camera and you have to make it happen. You’re moving into areas you’ve never been before. You’re asking people to cook for you… It’s really random.

Can you imagine doing that in America? Arrive and say hi. I’d try to do a different one in America. It’s difficult to get people… I’m invading their home space, I’m saying, “Can we set this thing up? And can you cook for us? We’ll give you some money, go and cook.” It’s quite invasive and it’s not necessarily that easy or straightforward. You do have to have an element of trust. Also, we cook a lot of food. It’s food for everyone. It’s like a party. I don’t actually like that many people watching but it’s inevitable in the village, everyone’s always there watching you.

There is that sense of party and also you have to direct them correctly, and explain what you’re doing and really engage them. Whenever I explain what it’s about, they go, “You’re showing our culture.” They get it. They’re down, they’re into it, they love it. People there are very good, they’re really good. When they’re good, they’re really good and performing in the most incredible way and understanding what it’s not about… There’s one woman and she was licking her lips and she was hamming it up. I’m just like, “No, it’s not what I want. You just got to… be.”

Those people that are most comfortable with themselves, they’re the ones that gave the best performance; they just were able to just be and focus; it’s really difficult. It’s not easy at all. Also, you’ve got to do it in one take, and if you fuck up once, you have to start all over again. You have to get it in one take. You have to have an environment where it’s very easy; but at the end of it, everyone’s whooping and it’s glorious. It’s actually a really beautiful moment. I love making these works. It’s not easy. I remember one of them, there were shootings right out there. There are some crazy times there because it’s not always the same.

Ogoniland is not safe, and has not always been safe to film in. This is me claiming a moment, claiming an approach to the land amidst all this craziness. So it’s not easy. When you get to the end of it, you’re just like, “Thank God.” Literally thank the Lord for this, and everyone’s grateful and thankful and we’re all eating. I often get really hungry. Often times I’m like, “Give me a plate.” So I have some food as well, and it’s really joyful. It’s a really joyful moment. In a way the installation is just a consequence. What is more important is the happening, the thing that happened and the moment we created.

That is the most important thing for me on some level. But then the consequential film at the end of it, it’s doing the job it needs to do, it’s going around. People are picking up on it. My films are like my babies, and they have different moments where they come up. Table Manners has been growing in the world and it’s going to be in Time Square, part of “The Midnight Moment” in November this year, which is exciting. No, it’s just this weird thing, where the work is growing and growing and growing and growing. I’m excited to show all our different faces. I’m excited to share our names, place names with the people’s names in each sequence.

I’m excited to show our food. I’m excited for people to commune, because most of the world has gotten oil from our part of the world and we have really suffered, as a result of this industry. This is an opportunity for people to sit down and share, and commune with these people that they would never meet in a million years. So, yes. But then the moment [of the art making] itself is also the power.

BL. You said that you’re not interested in identity or identity politics, and that culture and identity are utterly mundane and transitory. Do you want to go into that a little bit of what you mean by that?

ZS-W. I think people think my work is about identity, and in a way, yes, it’s cultural I suppose, in some ways. I care about culture, but I am also someone, when I talk about decolonizing, I’m not talking about decolonizing necessarily from an oppressor. I don’t know who the oppressor is. People seem to think that I know, I don’t know who the oppressor is, it’s multiple oppressors. I might be an oppressor; I might oppress myself. I’m not interested in simplistic readings of politics. Like this moment, for example, is a difficult one for me, because I just think that in America, things are very much reduced to only race.

For me, making work about [race] is, also, in a way, weird, especially if you’re black, because it does this weird thing of actually centralizing white people. When you say identity politics, it’s always about racism. It’s not about just the self and just enjoying yourself and understanding the self. It’s always about that clash and about the negativity. If identity politics was more joyful then it was about everything, then fine, but it just seems to be about oppression or not. I don’t see things that simplistically and I can’t do because, who did kill my father? It wasn’t just the oil companies that exploited the murderous regime, it was Nigerians that killed him. That’s what I’ve grown up with.

I know that we totally oppress ourselves. That’s the core of my understanding of the world. I don’t see oppression from one place; it’s from multiple places. It can be within your own family, and it could be you. My reading is always much more complex. When we say identity politics, I think that people have a particular understanding of it. I don’t think it has to mean something that is narrow and reductive as it is. I think that ultimately, we have to get braver in the art world; we have to start to be the space where we talk about these things. Not on the one hand reacting and begging for forgiveness from some kids on Twitter, on one hand, but then also not facing your donor class on the other.

You’re just trying to satisfy these two sides and be performatively politically correct and woke on one hand, but on the other hand, just trying to placate your donor class. I just think it’s bullshit. I think museums and galleries need to find their balls and actually also go beyond identity, because it’s boring. There’s no truth there. It’s just a performance. For me, it’s about going underneath that surface, the subcutaneous layer. Even in Nigeria, when I’m talking about masquerade, I’m talking about this, this is surface culture. There’s something going on underneath and that’s the underneath, that’s the bit that I’m interested in and that’s where my work is going.

The surface culture is the tool to get to this underground place that you can’t see with the visible eye. That’s the stuff that I care about. That’s the stuff I’m interested in. So you’re watching Table Manners, but you’re supposed to get into some state where actually you access a different truth; but you are not in the way of trying to control. You don’t have that control. You might watch the work, but for me, when you watch my work, the idea is to get to this particular. I always want to use the word fugue state, but then I looked it up it’s totally not what it is. But I want to reclaim fugue state, because when you are listening to a fugue and when you’re listening to Bach, you do get to a particular place.

You get to a particular hypnotic place ideally, if you let yourself go and submit to the work, and you access somewhere different. I can’t tell you what that place is and what’s in that place. That is your relationship with that space and place. That’s not for me, but a culture can get you there. That’s why I’m not interested in making work about racism. I’m not going to privilege what white people did to us in my work. I don’t give a shit. I care about us, actually, and I think that whatever the fruits are, anyone can enjoy it. My work comes from a deep love for black people, my people, Nigerians, Ogonis. That’s where it comes from. It’s obvious black lives matter to me. It’s obvious.

Barbara, what do you think by the way? I’m interested in what you think about that.

BL. I have to say I’m really much more aligned with you. I’m very interested in what people have to say but I’m really sickened by knee jerk reaction in this country right now. I’ve lost ten pounds because the whole situation has been so upsetting to me and I honestly don’t know quite what to do.

ZS-W. See I gained ten pounds. I really wish I could lose ten pounds. Yeah, it’s making me frightened, and I read everything let me tell you. I do my deep dive into the far right, I do a deep dive into the far left, I do everything. As an artist, that’s your job. I don’t really understand why suddenly, especially if you’re a black artist, you have to have a particular idea you’re supposed to promote. Art is a place where we’re supposed to be able to have this conversation. I thought that art was supposed to be iconoclastic. I certainly am, but my views are rooted in love, always. Always, and they’re not rooted in revenge and I have every right to want revenge considering what’s happened in my family.

The way my father was killed, but also the fact that every single man in my family is now dead, including my latest brother in April. I should be the angriest person in the world. This is how you survive it. This is how you survive trauma, it’s through love, and it’s through joy and it’s through openness. It’s that thing. That’s the only way that I know how to survive this, and art was the way that I had to do it. This is my only tool to survive this. My only tool. That’s why I don’t connect necessarily with the political moment, because it’s not even aligned with how people think, spiritually and privately.

You’re not supposed to revel in your victim status. If I did that, I would never be an artist. I’d be dead by now, if I reveled in victim status, and yet that’s what we’re asked to do politically. It’s outrageous.

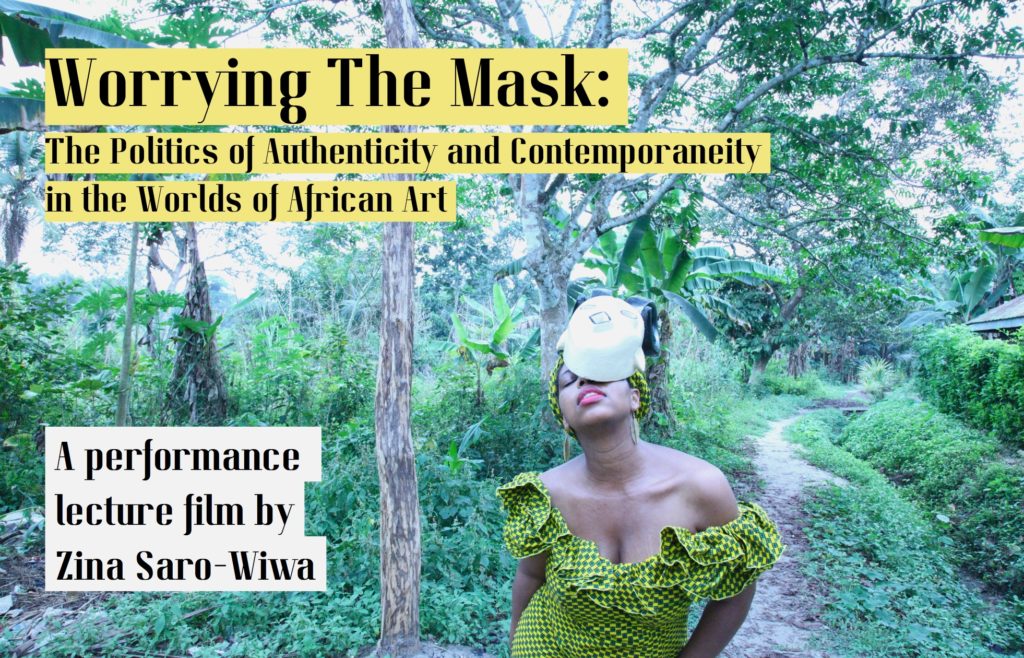

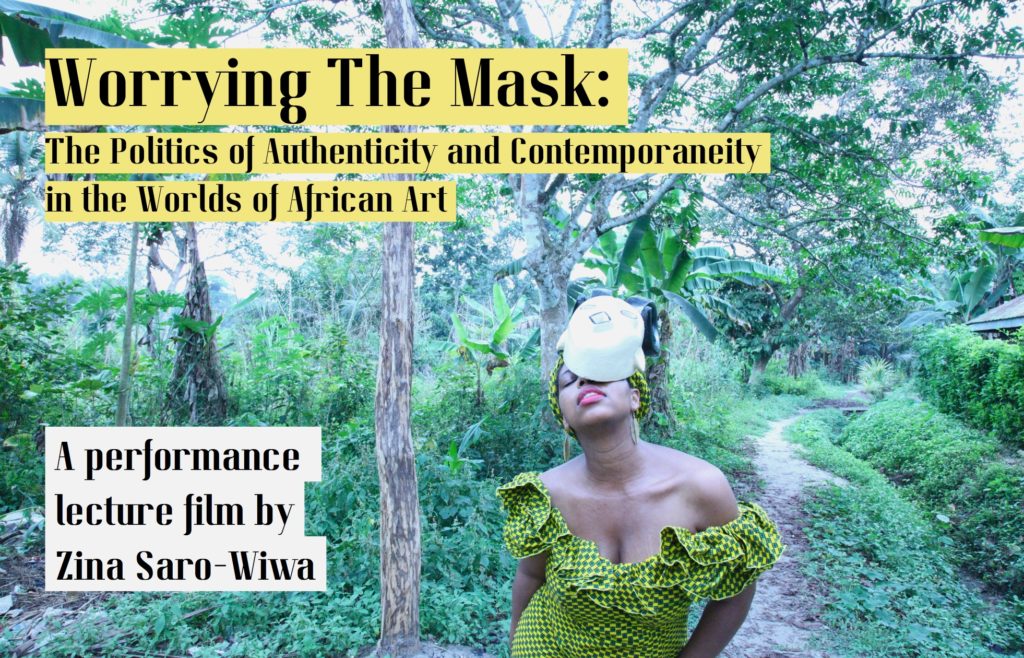

BL. Yes, I agree. Let me go on and into your latest work. It’s a very powerful essayistic performance lecture film called Worrying the Mask: The Politics of Authenticity and Contemporaneity in the Worlds of African Art. Now, it’s a very complicated, very deep, rich topic, which you cover so beautifully. I want to know more about your sincere interest in the Ogoni artist-carvers, and someone like one of the beautiful men in your film, the sculptor Thomas. It makes me wish I could visit Ogoniland with you and meet this man.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

ZS-W. You saying that is exactly what I wanted to do, because most people are terrified to visit Ogoniland because of all the things they’ve heard. But then you’re saying that it’s exactly what I want.

What I want is to encourage and to enable Nigeria to sort itself out so that we can invite people like you to come and enjoy and experience. This that is the dream. That is what we need. Absolutely.

BL. Promise is this individual who embodies a very old culture. You give him respect, and you give him the place in the Boys Quarters Project Space, because you showed his work there. In a way that seems like your mission, and I have to say, I’m really in awe of your resilience to do all of this.

ZS-W. Thank you. You’re a black artist in the world and black is important here for other people, not necessarily for me. But it seems to matter to other people. I kept on focusing on this cultural production, this contemporary traditional art making, and I just really wished I was making the work that would make me some money. Why am I so focused on this work? Now, it’s become clear to me as to why it’s important. This is what I mean about the Niger Delta having these gifts; it’s what I mean by the subcutaneous. You engage with the surface culture, then something else completely different comes out of it. What came out of it was this conversation about the role of art.

What is art supposed to actually be doing? My meditative tool is his sort of art making, and the fact that I can’t use it for cultural capital building in the world. It’s difficult for me to try and transform the fortunes of Ogoniland in the Niger Delta through art, because of these weird ideas around what constitutes valuable, traditional African art or not. That’s what the film was going through the motions of, when Promise’s art meets the rest of the world, why is it not seen as valuable? And why is that dangerous? Actually, this connects with the political moment now, it connects with what art is supposed to be doing, it connects with how people see black people, how we see ourselves.

It connects with all of those kinds of things and that’s what art practice does. If you submit to the work, it teaches you these things. It’s taken me eleven years to get to this point as an artist. For me, it has taught me all of this and it’s still teaching me and it’s giving me my next book, and it’s giving me my next artworks that actually connect with now, the here and now and with LA, and with America and with the world. There is a connection there, because art knows better than you. You don’t know better than you. I don’t see why you’re allowing external, rigid politics to inform what you’re actually going to make. No, I let art tell me what to make, and that’s what these artists in Ogoniland do.

They channel something greater than themselves. That’s why I have no interest in political art that just speak to this moment in a particular shallow way. That’s not of God, that’s not something that’s greater than you. That’s not interesting to me.

BL. We have just basically one more question. My last question is, what I ask everybody in this series, do you consider yourself a media artist?

ZS-W. Well, I’ve never called myself a media artist. In the past, it was video artist, but then when food started to assert itself in my practice, then I realized that that term didn’t fully cover it. When I realized that my curating was a part of my practice and not separate, it challenged that term also. When I realized that the actual gallery I set up and the new spaces I’m about to set up were actual sculptures, I realized that I’m not just a video artist. What is media anyway? It literally means a medium, or a way of doing something, or telling a story. I can use any medium to tell a story, I feel. But I think that within my practice, I’m trying to evolve what it means to be an artist. What is art truly for?

My practice operates in a very specific and strange place. It is intimately connected to my very survival. Nothing I do is not art; it’s everywhere for me, it’s how I survive. So, no, video artist doesn’t cut it. Maybe media artist does if you expand the idea of what media is, but truthfully, at this point, I feel like I’m just Zina her doing her thing. Everything for me is art.

BL. On behalf of Zina Saro-Wiwa, thanks for joining us for this episode of Barbara London Calling. Be sure to like and subscribe so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram @barbara_london_calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed. Support for Barbara London Calling is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and Independent Curators International (ICI) in conjunction with their upcoming exhibitions “Seeing Sound,” which I curated.

This conversation was recorded on July 10, 2020 and has been edited for length and clarity.

This series is produced by Bower Blue, with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music. Thanks again for listening. We’ll see you next time.

Bio, Images, & Video

Born 1976 in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, Zina Saro-Wiwa lives in Los Angeles, and works with video, in addition to photography, sculpture, sound and food. She also runs a practice in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, where she founded the contemporary art gallery Boys’ Quarters Space. She is artist-in-residence at UCLA 2020-2021 out of which she is establishing a radical think tank called The Illicit Gin Institute

The work features a set of actions that explore mourning rituals and addresses the role of performance in grieving.

This wittily subversive narrative draws upon the stylistic and visual conventions of Nigeria’s Nollywood film industry. In use here is the Nollywood-inspired device of wig-wearing, as a critique of the unforgiving treatment of single women in Nollywood and Nigeria.

The documentary explores African culture through the anecdotes and commentary of London-based Africans and Africaphiles. The interviewees include artist Yinka Shonibare, actors Colin Firth and Lupita Nyong’o (pictured), filmmaker John Akomfrah, among others.

Karikpo Pipeline (2015) by Zina Saro-Wiwa 5-channel video (EXCERPT) from ZSW Studio on Vimeo.

Dancers perform Karikpo, an acrobatic masquerade unique to the Ogoni people of the Niger Delta. Their masks and movements mimic the antelope. The performers move playfully over the disused pipelines, wellheads, and other infrastructure of oil extraction, all nestled into lush but degraded surroundings. Saro-Wiwa invites the viewer to rethink the connection between land and the nature of power.

Table Manners (Season Two): Friday Eats Hairy Leg Crab. 2016-2018.

With great gusto and relish, a denizen of the Niger Delta delivers a distinctive eating performance in a colorful setting. The video has a lot to do with place and power. The artist notes, “A powerful exchange takes place when one not only eats a meal but watches a meal being consumed. One is filled up with an unexplainable and potent metaphysical energy that we normally pay no attention to.”

In an absorbing lecture-performance, Saro-Wiwa considers how African masks live both in the West and in Africa and how these African art worlds impact one another. She challenges the call for restitution of African objects from Europe to Africa citing storytelling and not geography as the primary issue of concern and questioning the value systems that uphold antique African carvings and denigrate contemporary traditional works which still have an important role to play in telling African stories.