This is Barbara London Calling. Welcome once again to my podcast series about the wild world of media art. I’m calling media artists from around the world, many of whom I’ve worked with as an author and curator. Together we’re exploring what motivates and inspires these artists, and how they see the world as media artists working at the forefront of technology and creativity.

Today I’m calling Samson Young, a Hong Kong–based artist whom I consider to be one of the most talented investigators of sound as art.

Samson works in a broad range of disciplines: music composition, performance, installation, sound, video, drawing, and design. His artwork is elegant yet razor-sharp, and sometimes political in nature, as he addresses the vicissitudes of language and history.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Samson, thanks so much for joining me.

SAMSON YOUNG: Thanks, Barbara, for having me.

Transcript

BL. So, let’s begin. You received a PhD in music composition from Princeton, a Master of Philosophy in music composition from the University of Hong Kong, and a BA in music philosophy and gender studies from the University of Sydney. I’m curious: How did growing up in Hong Kong shape your outlook on life, and how did you feel that outlook change once you came to the U.S.?

SY. I grew up in Hong Kong, and I think my experience of growing up in Hong Kong is probably not so dissimilar to the experience of growing up in another large, condensed urban area. We consumed a lot of popular culture coming from the U.S. and U.K., but also of course from Japan. But Hong Kong also had, when I was growing up, a very strong popular culture. A lot of films were made in Hong Kong. So, all of those things, I guess, I still carry with me. The popular-culture industry here is not as strong anymore. I think those early years of being immersed in Hong Kong pop culture still left a mark on me.

And then I grew up in Sydney, Australia. I spent my teenage years there, and I did my undergrad studies there, as you have mentioned. When I was living there, it was a particularly conservative time. There was a little bit of an anti-immigrant—especially an anti-Asian immigrant—sentiment and some resentment. Pauline Hanson, a conservative politician who was running on an anti-immigrant platform, was gaining popularity. So I think in some way that experience shaped me, as well.

And of course, then the U.S. is a whole different thing. But during graduate school I mostly spent my time in New York. As soon as I was able to, I moved out of Princeton, New Jersey, out of the college town and lived in New York.

In many ways that was much more like being in Hong Kong, in terms of the mix of people or the density of the city. But of course, in terms of the offering in culture, there’s no comparison. There’s a lot more happening in New York.

BL. Let’s move on to a series of works that you’ve done that involve muting as a technique and concept. And perhaps we can zone in on one work, your video-sound installation Muted Lions Dance, which can be seen as a re-imagining and a reconstruction of the auditory. As I understand, it’s a single-channel video projection, and traditional Chinese performers dance in costume without the usual percussive sounds of the drums playing with them.

I’m fascinated by how it is that the sounds of the performers’ own physical exertion—their feet hitting the ground, their deep inhales and exhales, and the rustling of their clothes—come to the forefront. Could you tell me a little more about this idea of muting. I know you’ve said, ‟Muting is not the same as doing nothing.”

SY. Maybe a good place to start would be to go back to how that whole series was originally conceived. The Muted Lion Dance actually belongs to a series of works titled Muted Situations. Initially, these Muted Situations exist as text instruction scores. They’re just text describing a situation to be realized. And then, over the years, I have realized some of these text-based performances and made them into live performances, recordings, or videos, or a combination of these things. Right now, there are twenty-two of them, and the Muted Lion Dance is one of the early ones, actually.

I first made this series of work in response to a prompt given to me by a curator. For one year of the Manchester Asia Triennial, I was given a space inside of a library as the venue for making a sound installation. It’s inside of this historic building, this pretty old library, but at a quieter wing of the library. So, you’re not really supposed to be making something that is very loud. That paradox interested me, like thinking about how you would make a sound piece that could live inside of a library and what sort of environment that really is for a sound installation, what sort of context that really is.

But if you start to think about what a library is in terms of the sound that you hear, it’s not really an entirely silent environment. What you get are very specific layers of sounds that are suppressed, usually the speaking voice. So, of course, you’re trying to whisper and you’re trying to keep conversation at a low level, and certainly speaking on the phone is not something that is permitted. So, that layer certainly is suppressed. But then, the staff at the library or the people who are shelving the books and pushing the carts around, these are certainly sounds that you can make.

And if you are, say, opening and closing your backpack and taking books in and out of the backpack, that certainly is allowed and people make sound doing those things. And there are announcements coming from the public announcement system. There are other layers of sound that are still there and they are in some way permitted. It got me thinking about how there are different parallel times, I guess, happening. I was trying to imagine a situation when you can switch on and off some of these times, these layers of sound at will. That thinking was what the original impulse of the Muted Situation is.

In each of these situations there is a very specific layer of sound that is intended to be muted. With the Muted Lion Dance it’s the percussion noises and sounds that are to be taken out. But then, of course, there are other sounds that are not only allowed to emerge because you’ve taken out the loudest thing. But actually, there’s an active investment in reinvesting in those other layers of sound so they don’t diminish for as much as possible, only because you’ve muted one layer of sound. With the Lion Dance, for example, it’s actually really quite difficult for the dancers to dance without the percussion music, because that’s what they get their bearing from.

But because it’s very important in the spirit of the Muted Situation series that these performances are, for as far as possible, still performed with the same level of energy and the same performative intent. So, then we had to almost reverse-engineer it, and figure out a way for dancers to be able to dance with confidence. So, they had an earpiece in their ear, and the coach of the lion dancing team was actually counting in their head. Although they were not listening to the percussion music, they were still getting the rhythm and getting coordinated that way.

That’s specifically the Muted Lion Dance, but then it works in the same spirit for the other Muted Situations as well, a muted boxing match, or a muted string quartet. Most recently we had the Muted Orchestra, Number 22, which is the last one in the series. The series finished with Number 22, and I’m not going to make any more of those.

BL. I know from the Muted Lion Dance, you’re very, very, very particular about the speakers in the installation. That’s what a visitor to an exhibition of the work experiences. One is viewing the dance, but as you have described, the sound is so important. You very carefully place the speakers within the architecture of the space. Do you want to talk about that?

SY. When I make sound pieces or video pieces that have an important sound component, which is for me most often the case, I try to be specific with the speakers. I think when you are mixing the same music with more layers for different speakers there’s a little more room for, let’s say, a discrepancy between different kinds of speakers. Of course, the quality of sound between different speakers is always going to be different. But when you have a musical composition with many layers of sound, there is more information for the ear to hold onto even if the content of the sound or maybe the equalization of the sound shifts between different speakers.

But with a piece like the Muted Lion Dance, for example, so much of it is noise and noise without, let’s say, melodic content. So, there is much less information there, but actually because of that, because you’re only really hearing, for example, these sounds, like, stomping of the feet on the desk and the rattling of the lion’s head between speakers, because that’s what you’re focusing on, they can really sound quite different. By specifying models of speakers, I just know that they’re going to sound more like the way I mix them. It’s not a minor thing, actually. But there is a simple solution to it, which is to be specific with a speaker.

Actually, the other thing is volume level. Of course, it really depends on the [exhibition] space too, and you have to make adjustments according to the space. But knowing what kind of speakers you’re going to be using, and being used to the dynamic range of those speakers, also makes a big difference.

BL. This is a very good time to now move on to a fantastic work I saw of yours at the Guggenheim Museum: the multi-part installation called Possible Music #1 (feat/ NESS & Shane Aspegren), which was part of the “One Hand Clapping” group show. I walked into this gallery at the Guggenheim and you’d so totally transformed it, with cobalt blue carpet, aqua-colored walls, and curious shaped objects on the floor. The latter were pentagonal speakers, each with very stalky artificial flowers poking out. The speakers, I believe, played the sound track for your video displayed on a flat screen on the gallery wall, Emulating Sounds of Imagined Horn Instruments.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

This was an incredible work to me, and I actually returned at least four times. You devised such visual and sonic complexity. I’m curious, there are many questions here. For the brass instruments, you created the sound with an algorithm. How did you do that?

SY. The software that I used to generate those brass sounds is a physical modeling software. Physical modeling is a technique in computer sound synthesis, which, in a nutshell, is a way to simulate the sound of an acoustic instrument by describing the physical properties of that instrument. So, for example, if you’re trying to make the sound of a trumpet, which is what I did, you would give the software a description of the instrument’s dimensions. You would tell what material the trumpet is made of. You would also say, “Control finer details,” which actually affect the sound, which you can also punch into the model, things like the temperature of the breath.

I was using this NESS software, N-E-S-S, which was developed by the NESS team at the University of Edinburgh. Stefan Bilbao is the principal investigator of the research team. I took a residency at the University of Edinburgh through the Talbot Rice Gallery, and I got to know the NESS team of researchers. They actually live somewhere between the physics department and the music department. My initial meeting with Stefan was actually in the physics department. At that point, I was still exploring different people within the University that I might be interested in collaborating with. But as soon as I met the NESS group, I knew I wanted to work with them.

Their software is not a commercial software. It’s not made to be easy to use. Actually, it’s very code-based. So, the NESS team taught me how to use the software. And as soon as I got my head around the software, I started kind of abusing it. So, I started doing things that you are not supposed to do. For example, one of the parameters in the synthesis is the breath, the temperature of the breath, which usually for their application stays at a constant level. But, of course, I started tweaking it, so you would get theoretically fire-dragon breath, or ice-dragon breath, and trying to see what that would sound like.

I started making really, really big trumpets, really long trumpets that couldn’t possibly exist in the real world. I had a lot of fun with it. Both me and Stefan Bilbao from the group realized that these are sounds that, A, the research group doesn’t really go into that sort of territory. And, B, it’s also the kind of sounds that are not easy to make with other synthesis techniques. I’m always very interested in this when I’m making things with a tool, such as the NESS software. I’m interested in exploring corners of that field, to make things that are otherwise maybe difficult or awkward through other ways.

With that software, I generated a bunch of instruments that are impossible to exist in the real world. Then I generated some very short compositions with these unusual instruments, and I mixed them with samples of recordings of a bugle call. So, I imagined them to be this collection of monstrous, weird military bugle calls that you would hear throughout the day, let’s say, if you’re in the army, signal calls that basically punctuate your day.

BL. I’m very fortunate, because I’ve met you in many cities around the world. That means I’ve seen a range of your work in these places. This past August you were briefly in Denmark and I experienced the performance you did, entitled Three Cases of Echoic Mimicry, or, Three Attempts at Hearing Outside My Own F-ing Head, in which you used the concept from social psychology called Echoic Mimicry. You were examining the genealogy of a song called Mo Li Hua, the Jasmine Flower song. So, tell me more about this. I know again it’s another very complicated work, which was performative, and which I saw you perform alone with a video projection behind you. It’s complex, so maybe you could dive into the ideas.

SY. It’s a bit of a mouthful to explain. I think my work may be increasingly getting that way. They are so dense with references. This is my perspective. Maybe the audience feels differently, or maybe when you view it you see it differently. But when there’s a certain level of density of information, beyond a certain point people actually give up trying to rationalize it. Because they are so lost in it, then they actually soak in other things. So, they are not so bogged down in trying to understand everything, and they begin to see the color, they begin to see the humor, they begin to let these things that just hit them in a more direct way.

That’s been the inclination in the last couple of years. But specifically, with this one piece, I was researching the history of this very famous folk song, the Jasmine Flower song. It’s a Chinese folk song, Mo Li Hua, but it’s not any old Chinese folk song. It’s one that is very connected to the national psyche. It’s used in a lot of sporting events, or in the annual New Year television show, which often would have performances of this song. It’s been used by the saxophonist Kenny G. and the singer Celine Dion when they do their performance on CCTV, and makes people very happy. It’s a special song.

When I looked into the history of this song, the funny thing that I discovered was that the melody we now know and associate with the song Jasmine Flower, if you look at the genealogy of the melody, it actually came from a transcription of the song. As part of the first English Embassy to China, there was a scholar and diplomat by the name of John Barrow. He transcribed and published the melody in his book entitled Travels in China. In that transcription there’s the melody, but there’s also some lyrics that were written down.

Now, if you look at the lyrics of that song and compare those lyrics to how we know the song today, there are definitely a lot of inaccuracies. It’s also interesting if you compare and look at the melody in the John Barrow version with a couple of sources that have survived inside of China and in Japan. A lot of sources within China are lost. Sometimes when we look at old Chinese music, we need to look at sources that have survived in Japan. The version that has survived in Japan and inside of China are both more similar to each other than they are to the John Barrow version.

We can say with some level of certainty that the song itself has evolved, but somehow the version that we know today of the , Jasmine Flower song actually came from this much older version that was transcribed by an English person. So, that was the point of departure for the piece. Through that idea of transcription culture being reflected back at you, I was, I guess, thinking about cultural appropriation and authenticity, but with actually a rather open attitude. At the end I think, I guess what I was trying to say is that it’s not really fruitful and productive to try to police these territories.

The result of all that thinking was a two-channel video, where in the installation version you would have one channel where you see a horse delivering a lecture on the history and the genealogy of the Jasmine Flower song, and then it moved on to talk about Kenny G., and then talked about later “Tang Court Music” (Togaku is Japanese for Tang Court Music) and how it survived in Japan. So, that’s one channel.

In the other channel there’s a musical performance of an original composition, where I was basically very forcefully trying to combine the melody and lyrics of the Mo Li Hua song transcription (the) inaccurate one from the John Barrow Travels in China book, and combined it with “tourist instruments,” musical instruments made for touristic consumption, a Japanese melody, and performed an ensemble that included me on a musical instrument that were created for touristic consumption, a horse, a harpsichord, and two singers.

BL. I saw you perform the work in costume with your head covered in a mask, as if you were a horse …

SY. No, I perform as a horse in the lecture version.

BL. The performance-lecture was impressive. Moving on.

In 2018 you were artist-in-residence at the University of Chicago, where you focused on research for a complex multimedia exhibition, “Silver Moon or Golden Star. Which Will You Buy Me?” at the Smart Museum. I know it’s loosely inspired by the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. What was it about that sense of idealism at the World’s Fair that felt so relevant for you?

SY. It was at a time when I was thinking a lot about utopia. In that show there were three music videos, and the one that directly references the Chicago World’s Fair was actually the last one in the trilogy. In the second video, for example, I was looking at Kang Youwei, an important figure in modern Chinese history. He’s maybe the only, somewhat utopian thinker in the modern history of China. The history of modern China is not exactly filled to the brim with utopian thinkers and utopian literature.

I was not actually focusing on him himself, but on someone who worked for him in Canada, for the Emperor Restoration Association in Canada, the Canadian chapter at the turn of the century. This gentleman by the name of Alexander Cumyow, Won Cumyow, was allegedly the first Canadian-Chinese to be born in Canada. Very good in English, he worked as a legal clerk, but he also penned a lot of the petition letters to the different heads of state for the Emperor Restoration Association, to try to convince other heads of state to restore the last Emperor of China on the throne. Obviously, he was good in English and he was very well educated.

The interesting thing about him is that he actually never traveled to China. I was imagining that he had a somewhat romanticized image of the nation, from his perspective, and also in the context of the kind of racial discrimination that he would have faced. When I was making those three videos, I was thinking a lot about a sort of utopia, how it felt and how utopian thinking bypasses logic in rational thinking. Those three animations, I call them the Utopia Trilogy, were looking at those things. When I started working on the trilogy, I already knew that I was going to work towards the Chicago World’s Fair.

To think about utopia, it’s such a big topic and I thought that I needed to work my way towards it. I built this up both by repeating the form, but also by looking at this through different cultures and different times.

BL. I was fortunate to be in Chicago at the time of the opening, and also, I was there to hear a remarkable performance that you developed with a high school girls’ choir. How did that come about? And did that have a utopian element too?

The Chicago High School for the Arts Treble Choir led by Natalie Chami performing E. Markham Lee’s “Dream-Seller” (1904) at Symphony Center, Chicago, 2019

Photo: Courtesy Todd Rosenberg Photography

SY. In the performance, we tried to perform and restage some of the music that was heard at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. When I was digging through the archive of materials related to the Fair at the University of Chicago library, we found the score for the theme song of the Fair itself, and also a score for the theme song that was written for the Sky Ride that was at the Fair. We performed those two songs, and we also performed a choral piece titled The Dream Seller. It’s a choral piece that I sang when I was young and performing in a children’s choir. It’s basically a lullaby and is very soothing. The music is very peaceful; there’s nothing dissonant about the song.

The song is talking about this dream seller that is trying to sell you a silver moon or a golden star, these beautiful dreams. But I remember specifically feeling, that by trying to picture what that dream seller looked like, and remembering the act of picturing what that dream seller looked like, I recalled the feeling. That’s actually where the title of the show came from, “Silver Moon or Golden Star. Which Will You Buy of Me?” In a nutshell, in these three music videos and also in this show, I wasn’t trying to look at where certain aspirational ideology comes from geographically. No, I wasn’t trying to disassociate part of ideology and associate it with a very specific geographical location.

The idea that I’m trying to think through is actually something that is a little difficult. That show hasn’t happened long enough ago yet for me to be able to reflect fully upon it. But I think what I was trying to think about is, if there is certain ideological thinking, certain habits of aspiration, certain warm feelings towards one view of the world over the other, they have become so ingrained in me that I have devoured to such an extent that I can’t really say that this is not a part of me. They’re all a part of me, and I can’t really separate part of myself and pretend that certain parts are not me. I haven’t fully digested them.

But I also try to think both in images and in music. I was trying to think about how I feel about these things. So, in the final footage in the animation, for example, there are these images, like many references, to feelings about utopia. Some are more historical, but some are kind of quite absurd. For example, Miracle Whip, which I’m sure many people may be disgusted by. But for me Miracle Whip is associated with a very specific memory. It’s about this very sweet tangy salad that my mom used to make that would be sitting in the fridge, something that you could snack on when you’d come home.

So, it’s about a certain feeling of warmth that you have. And it’s also because Miracle Whip first came into being at the Chicago World’s Fair. It was promoted to the public as this sort of replacement mayonnaise, because at that point they had come out with the technology to make Miracle Whip. But regardless of the historical fact, where that thing came from and how Miracle Whip arrived, and how it was marketed in Hong Kong, I cannot disassociate that feeling of warmth towards Miracle Whip.

BL. Last year your project for Performa 19 was a collaboration, and you told me that it was the most complex work you’ve ever undertaken. Why was that?

SY. Well, there were just so many moving parts. Having to choreograph the big cherry picker cranes and not knowing fully how those things work until really the moment when I see them and see the musicians on them. And freaking out about the musicians just falling off those machines. Also, there’s just a lot of music. There was animation, there were lyrics that I co-wrote with Eliza Lee, and there were costumes.

There were a lot of things going on, and I tried to be involved in everything. I designed the costume myself, but I had some help fabricating them. There were just many elements. So, technically that’s why it’s complicated. It was just a very nerve-wracking experience. I’m very glad that it happened, and it felt a little surreal. Still we were able to pull it off. I was very glad that I had that experience.

BL. It’s a complicated piece. You used construction cranes and you had performers. Were people on the cranes? I was away when this happened.

SY. This part of Performa 19 happened at Castle Williams on Governors Island. The audience was standing on one side of the half circle, and then on the other side of the circle we had five cherry picker cranes. The cranes had costumes on them, things that looked a little bit like ballet tutus. We had four electric guitar players and one singer. The electric guitar players were members of Dither, an electric guitar quartet from New York that I’ve worked with in the past and was very happy to work with again. And then we had the singer was Michael Schiefel, who is a longtime collaborator. They all also were dressed in costumes.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Then we had one additional performer, Eliza Li, who helped me with the Cantonese lyrics. We had some parts that had Cantonese lyrics to them, but it was mostly in English. Eliza Li is also a Cantonese opera singer, so she performed in the traditional Cantonese opera style in two of the scenes. The performers were on the big cranes, and the machines were moving up and down, getting closer to the audience and further away from the audience at different times. There is a choreography to how these machines moved and crossed each other. There’s the visual element and they were sort of dancing.

But there’s actually a sound element and the reason why they were moving around so much. That was because the sound source and was actually married to each of the players. Meaning that electric guitar player one and his sound source was actually directly underneath him on the basket of the crane. So, we didn’t have one stereo field, but basically had a multichannel one. We had a five-speaker multichannel system. Each of those speakers were mounted underneath the basket of the moving crane, and so by moving the cranes around I was able to do some fun spatialization things with the piece.

At one point I was sending Eliza’s voice through these five speakers and they were just going around the room, which actually was the original thing that I was the most excited by, by having this multi-channel speaker system that could move away and closer to the audience as a part of the piece. You can have the speaker that is really hovering right above you, versus being three, four stories up from you and being quite far away.

BL. An amazing, complex work. In closing, I’d like to know how you work in the studio? Do you have a team? Are you there alone composing, writing?

SY. These days I’m alone in my studio. I have one main assistant. She’s mostly helping me with looking after records and the archive of photographs, and helping me sometimes with things like text and research. But she’s working from home these days because of COVID-19. And then on the production side, I have another person, Vv, who sometimes comes in to help me when I am going through a particularly heavy production period. If I have to get things shipped and I need to pack things, or if I need to prep the surface of a 3-D printed sculpture or something like this, she would come and help me.

That’s the team. But actually, most of the time I’m on my own in the studio. And I keep to a routine. I go in pretty early in the morning. I’m a morning person. And then I actually try to leave on most days before 6:00. So, I keep a pretty regular schedule.

BL. How have the last few months been for you? What impact has COVID-19 had, and what impact has the recent national unrest had on your practice?

SY. Right now in Hong Kong, we still have certain restrictions on gathering in place, but those are due to be eased out soon. We’ve actually never had a lockdown, per se. We have always been able to go out. You keep social distance, of course. And of course, everybody is wearing a mask when they’re outside. During this time, I’ve mostly been keeping to my own schedule and working on a couple of things that have been scheduled for the winter and the fall of this year. I got lucky in the sense that I had a bunch of production-heavy works that were truly out of the way before the shit hit the fan. So, I got all those things out of the way.

Then in terms of my schedule this year, I had a little bit of a gap in the middle of the year before the new productions in the fall anyway, so I was able to keep to a rhythm. But of course, even things in the fall are getting canceled now. But that’s the same for everybody, so it’s not so special. Although I have to say, I think everything that is going on around me, not only COVID-19, but of course you had mentioned there was the social movement in Hong Kong last year, which is seeing some fresh energy because of the National Security Law Proposal that’s now on the table.

All of those things have changed the way I think about things in ways that I can’t yet articulate, but it’s not a subtle way. I was thinking to myself the other day, if I and Orianna Cacchione, the Curator from the Smart Museum, if we were to have a discussion about making a show for Smart Museum two years into the future, the show would look very different. Not in a topical sense, not like I necessarily mean that I want to respond to the situation now.

Even if I’m working on the same set of topics, this idea of utopia or any other topic, I feel like the show will come out looking very different. But it’s something that I’m not yet able to articulate. But it’s certainly something that is on my mind.

BL. Here is my last question, my very last, I promise. My last question that I ask everybody who generously, like you, agreed to take part in this conversation series. Do you consider yourself a media artist?

SY. I prefer the term ‟multimedia artist” because it means less. It’s imprecise and it’s so broad that it’s almost meaningless. So, I prefer it that way. I wouldn’t call myself a ‟media artist”, but I would be more comfortable calling myself a multimedia artist, I think.

BL. But not a sound artist?

SY. Yeah, not a sound artist. A multi-media artist or an artist. I do so many things that I feel like these labels are difficult.

BL. Thank you very much for sharing your knowledge and your thinking today. You’re a morning person and right now it’s night in Hong Kong, so thank you for breaking your pattern to be with me today. Thank you.

SY. Yeah. Thank you. Thank you.

This conversation was recorded on June 10, 2020 and has been edited for length and clarity.

Support for Barbara London Calling is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and Independent Curators International, in conjunction with their upcoming exhibition, “Seeing Sound,” which I curated. Be sure to like and subscribe so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow up on Instagram @Barbara_London_Calling and check out BarbaraLondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed. Barbara London Calling is produced by Bower Blue with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music. Thanks again for joining us. We’ll see you next time.

Images

A Lion Dance is staged, with four dancers and without the accompanying percussive music. The choreography, the costume, and all other factors pertaining to the performative intent of the work remain intact, as much as possible. As a result, during the performance other sounds are revealed, such as the intense breathing of the performers, the verbal communication and cues between the dancers, sounds of the lion’s head rattling, and the stomping of the feet.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

The sound performance was conceived around and in response to a series of night bombing videos, which the artist collected on YouTube and edited into a video without sound. The performer reenacts the sound, using airsoft pistol, audio interface, bass drum, compressed air, contact microphone, corn flakes, electric shavers, electrical sound toys, FM transmitter, glass bottle, laptop, mixer, ocean drum, rice, handheld radio, shotgun microphone, soil, tea leaves, thunder sheet, thunder tube, Tupperware, and wind chime.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

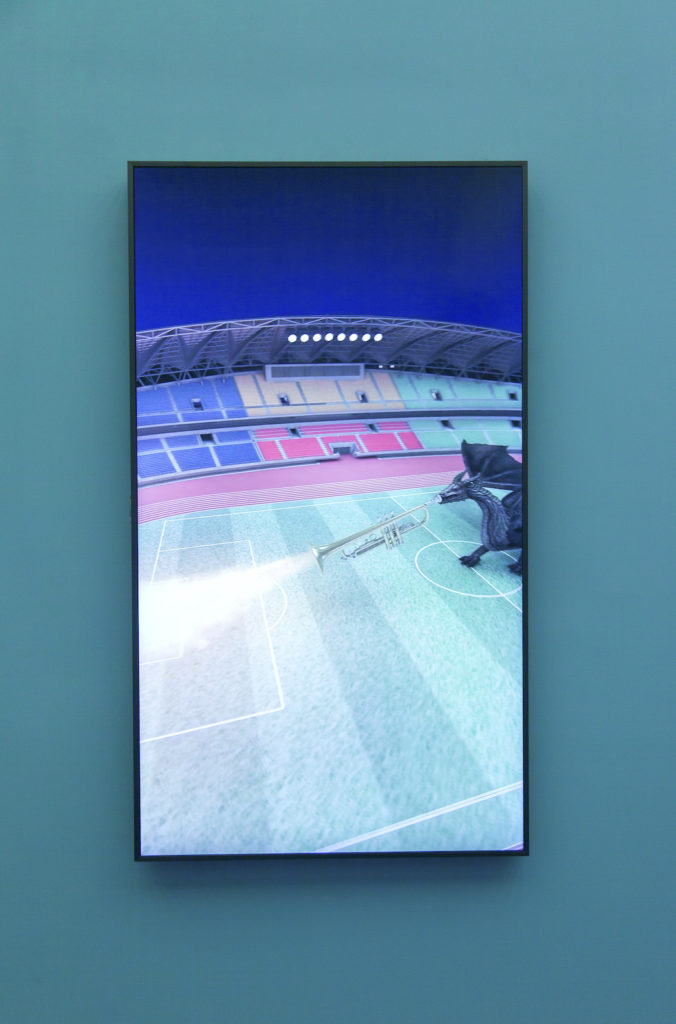

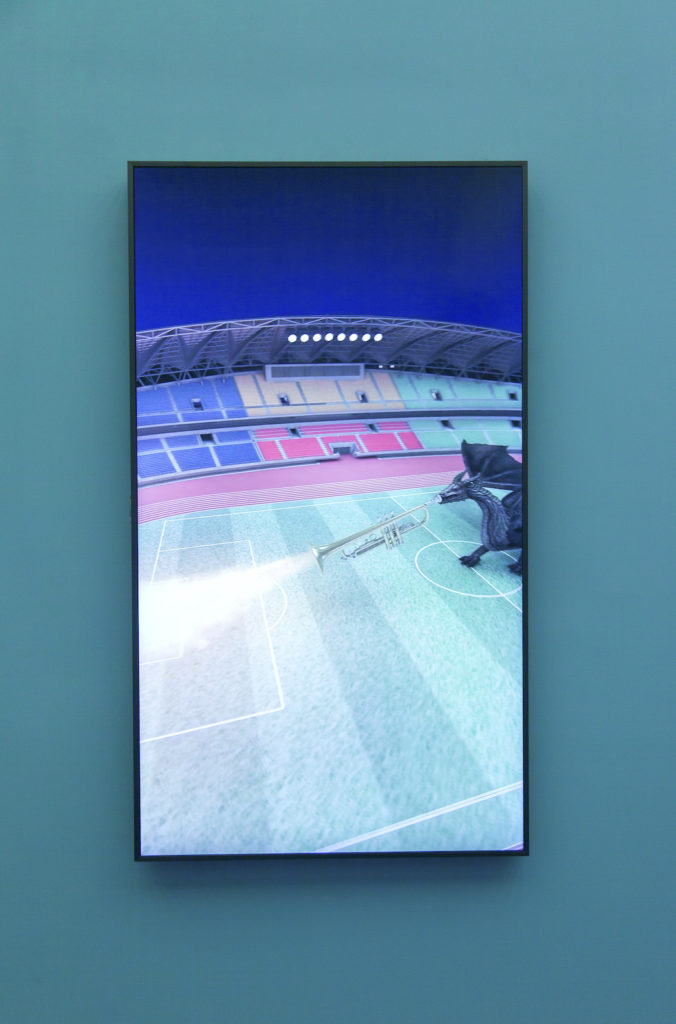

The eleven-channel sound installation includes 3D-printed acrylic sculpture with soft pastel, four 3D-printed nylon sculptures with soft pastel and colored pencil, 3D-printed rose gold, two framed watercolor and soft pastel on paper, costume with wool thread, artificial flowers, lamé, polyester, and silk flag, feathers with dye, and felt-tip pen on drumhead. The music was composed by the artist using brass instruments he created with software developed by NESS (Next Generation Sound Synthesis), a research project at the University of Edinburgh.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

[Work] The Immortals live at Castle Williams from Samson Young on Vimeo.

A Performa 19 commission, the multimedia music theater was composed for voice, a Cantonese opera vocalist, electric guitar quartet, live electronics, cherry-picker cranes, crane operators, costumes (silk-screen print on canvas), and animation.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

[Work] The World Falls Apart Into Facts (channel 2 of 3) from Samson Young on Vimeo.

The video performance-lecture developed out of the artist’s research into ‘Mo Li Hua’ (Jasmine Flower), a well-known Chinese folk song transcribed for Western audiences in the late eighteenth century,

The 2019 exhibition “Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will You Buy of Me?” at the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, was organized in three sections that related to the automobile, the mall, and the home, in reference to the 1938 Chicago World’s Fair. Each section revolved around an animated music video, the Utopia Trilogy (2018–19), and was accompanied by a fourth video, The world falls apart into facts #2.

The Chicago High School for the Arts Treble Choir led by Natalie Chami performing E. Markham Lee’s “Dream-Seller” (1904) at Symphony Center, Chicago, 2019

Photo: Courtesy Todd Rosenberg Photography