Today, I’m calling Marina Rosenfeld, a Brooklyn-based composer and sound and visual artist. In 1993, Marina orchestrated a performance artwork called Sheer Frost Orchestra. It was scored for seventeen women each playing an electric guitar using nothing but bottles of nail polish. Sitting in a line, the women were directed to play their guitars in a series of choreographed actions: drop, hop, drone, scratch and “A” for anything.

Marina received a degree in music from Harvard and an MFA in fine arts and music from CalArts. She’s currently an artist in residence at Nokia Bell Labs, where she found inspiration in an experimental prototype for a multi-microphone, nicknamed the Deathstar. Marina, welcome to “Barbara London Calling.” Thank you for joining me.

Marina Rosenfeld: I’m pleased to be here. Thank you for having me.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: I’ll start by saying that I’m forever impressed by your profound knowledge of 20th-century art, music and theory, and by your versatility. You hold degrees in both music and fine art, and you now co-chair the MFA program in music/sound at Bard College in upstate New York. I’m curious, did you grow up in a musical household?

MR: I did grow up in a musical household. My father was a professional orchestra musician; he was a cellist. I had, let’s say, an oblique, from-the-wings view of the entire, complicated social, political, economic music-making and -diffusing structure: from the side, from the rehearsal, from the pit orchestra, all that.

BL: I know you received a degree in music from Harvard in 1991. And in 1994, you received an MFA in fine arts and music from CalArts, which is located just North of Los Angeles. Harvard is often seen as an old boys’ institution, whereas CalArts, with its interdisciplinary program, is known for emphasizing the intersection of political, social and aesthetic questions. I’m curious, how did your time at Harvard and at CalArts separately and together help to shape your art practice?

MR: At Harvard, it’s almost impossible to overstate how difficult it was as a young female composer—or as someone coming into a consciousness of themselves as potentially a composer—how difficult it was to navigate the closed, conservative and exclusionary world of Harvard in the late ’80s in the music department. There had never been a female composer [professor] there, and I had an extremely difficult time. I was stripped of my residual excitement around the world I grew up in, and to a certain extent around musicianship, and the joyful, real labor of music. I would characterize the experience there in the late ’80s as predicated on a deeply ideological formalism that was really profoundly difficult to get through. So CalArts was like drinking from fresh water after being in the desert. And the Sheer Frost Orchestra, which you referenced, was my first piece, and it’s still out there. Sheer Frost Orchestra was like an explosion of a kind of concentrated negativity in relation to what I had been through and this sort of opening that appeared at CalArts.

BL: The work is from 1993 and it’s a very interesting hybrid. It’s orchestrated, it’s composed, but it’s very much in the field of performance art. Maybe you could talk a little bit about the work’s roots at CalArts, because performance art was very big in California at the time.

MR: The piece was my contribution to that semester’s crit conversation in Michael Asher’s famous Post Studio class. That was a very scintillating and influential scenario, to be in a room with my friends from school and Michael Asher (1943-2012) for a semester or two with, what I understood to be the task, to rebuild my mind around material concerns. It was a kind of exposure and banishment of all of the kind of pieties and sanctimony around prescribed definitions. What was music? What was art? What was performance? What constituted the material of a work? That’s sort of how I would see it.

I was like, “Well, I’m really mad.” I would define myself as someone with a kind of Adornian personality, in a way. I really felt very oppositional about what had taken place to bring me to this place where I couldn’t be the kind of artist I thought I had been training to be. Somehow, I felt kind of excluded, not just from the obvious exclusions I experienced at Harvard, but also, I had this strange high modernist training, and I would even venture to say childhood. In the context of California in the early nineties —at CalArts where everyone was so cool, like surfers and people in bands and stuff —I was like, “What’s my possibility here?”

The Sheer Frost Orchestra came out of experimenting with this instrument that I had no experience with, because I had been a trained pianist. I was like, “How do you play the electric guitar?” And how do you be a female body with the history of what I, at that time, felt were kind of false trainings and subjection, in a sense. How do you produce a different subjectivity in relation to this totally phallic, disgusting instrument? And then it was also, how do you bring a lot of women into this space of experimental music, where there had been a real wasteland, as far as that was concerned in my prior experience. My solution was to make a piece out of women and our troubled histories with this instrument.

BL: The clip we just heard comes from a festival called Dark Mofo held last June in Tasmania, and that’s twenty-five years after the piece was originally performed. It really continues to have teeth.

MR: I know it’s amazing. I never intended to do this piece more than once or twice, but it continues to be proposed to me. I have never initiated one after the first performance. Maybe for a couple of years I was like, “Let’s put it on again.” I hadn’t like ever heard of “social practice” at the time, but it’s definitely a work of proto-social practice in the sense that the work is the rehearsal, and the process, and the sociality of coming together, and learning this somewhat absurd music-making technique, borrowing all the equipment, lugging everything around, organizing ourselves into this sculptural set up. It’s quite galvanizing to be a part of apparently.

It seems insane now under quarantine to realize that last summer, for a week I went to Tasmania to do this festival. But that is the pre-COVID way of the artist, right, to just go anywhere? The previous year before that, I was in Chicago as part of this cool conference that the Goethe-Institute in Chicago put on called “Sexing Sound.” The women who organized the conference in Chicago took the work way beyond my original intentions, in terms of kind of mining their experience. They ended up publishing a series of first-person writing about it, what it was like to participate in what is now considered a work of historical feminist experimental music. That piece has a bit of a life of its own now.

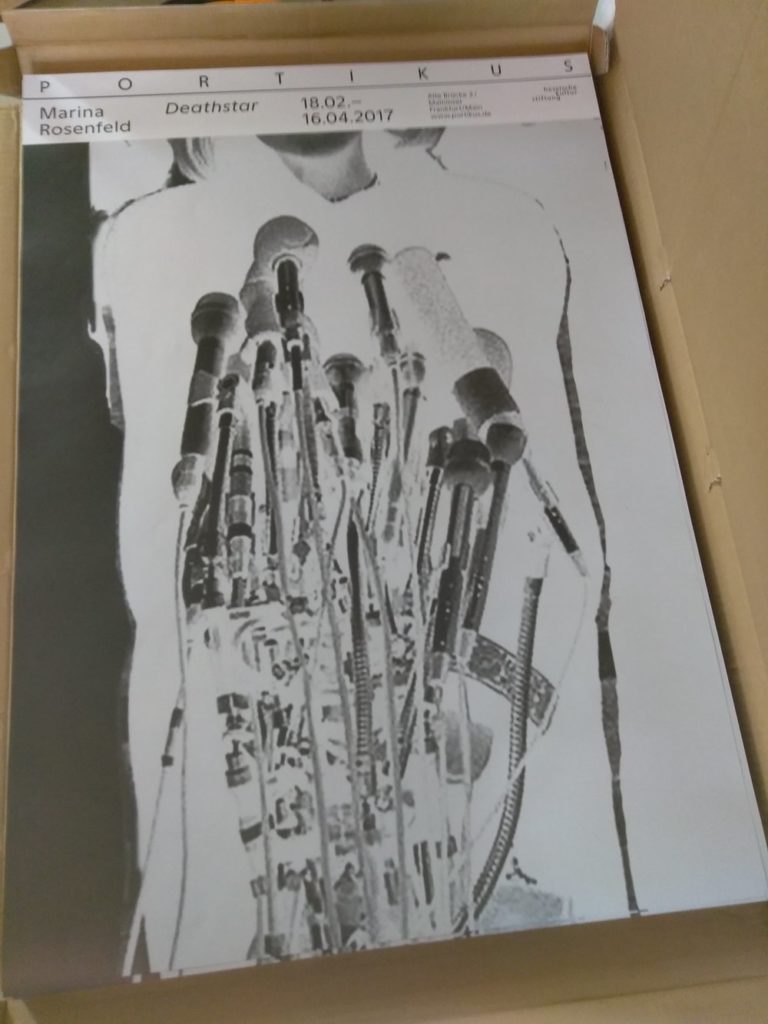

BL: I’m curious, in the years since Sheer Frost Orchestra, one could almost say that your work ratcheted up technologically. Currently you are artist-in-residence at Nokia Bell Labs. You have a series of recent works inspired by a lost prototype, a multi microphone, which Bell Labs engineers nicknamed Deathstar, which is a fantastic, almost sci-fi name.

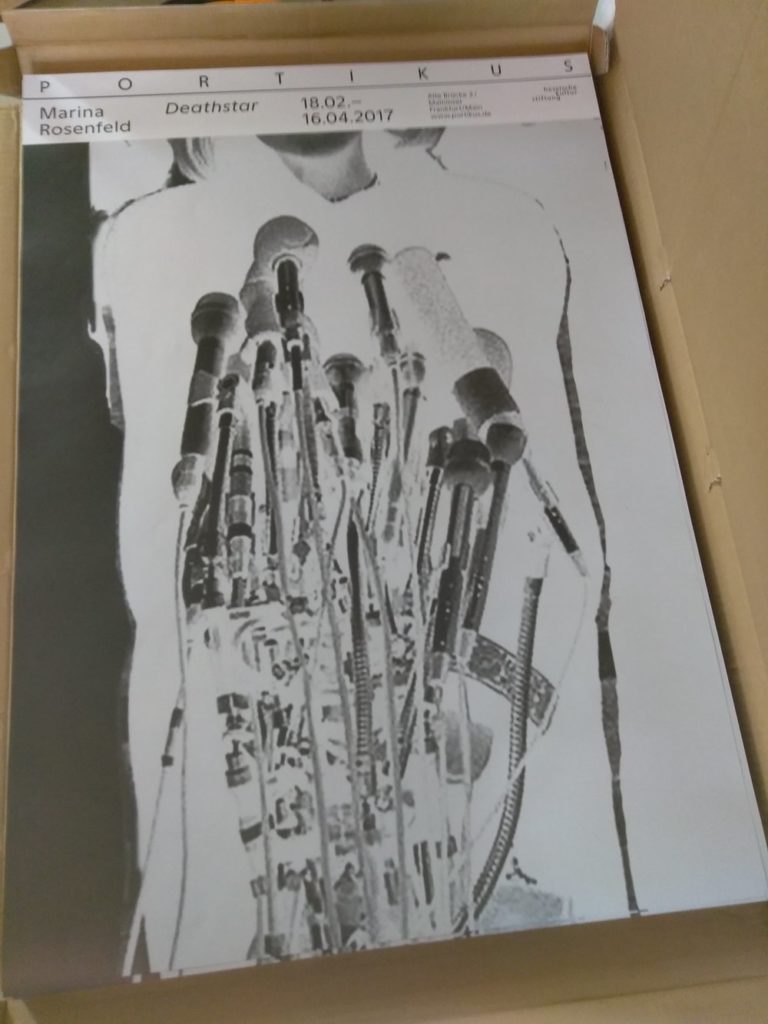

MR: The Deathstar was a prototype that I had occasion to try out around 2001/2002. I wasn’t able actually to locate the old Deathstar prototype, so I ended up building one based on some drawings and some memory. The original one did and my version does too, kind of look like the Star Wars Deathstar in the sense that it’s kind of globular with things protruding off of it. I guess audio gear generally does have a sort of Star Wars-esque ridiculousness, which I enjoy. So, I just went with that title.

I continue to work with the sounds of spaces, and bodies and architecture, and kind of configurations of bodies and machines. The Deathstar came to mind as a sort of interesting way to mobilize some really complex conditions that I encountered in Frankfurt at the exhibition space, Portikus.

BL: A few years ago I visited Portikus, and remember a kind of solid, but not huge space. What did the viewer see or the listener hear when they walked in? You invited a very acclaimed pianist to perform.

MR: What I ended up doing was creating a kind of a feedback environment, where whatever sounds were released into the space, let’s say, from some loud speakers on the ground, would travel and baffle and be buffeted by this concrete tower structure that Portikus is, and be received overhead by my Deathstar object, and then be recirculated into the space. So definitionally, that is a kind of feedback. Although we were able to keep it just at the precipice of the kind of feedback that will blow your eardrums and explode all of the gear by using some subtle delays. It was just right at this threshold of chaos without actually being chaotic. Essentially it was kind of just my voice, fragments of voice, and kind of noise fragments from the environment of the space, or in some cases, other notes, very diffused subliminal kind of marginalia of sound. Then it was recuperated into the system and redistributed.

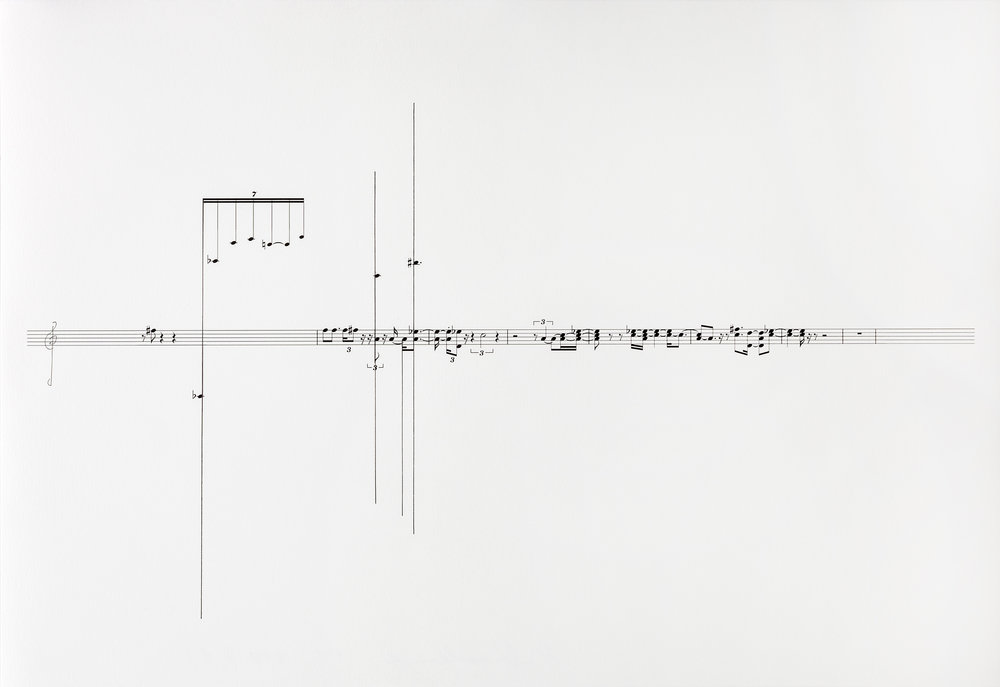

By the end of the exhibition, I was able to generate an extremely esoteric looking body of quasi notations. Then the virtuoso pianist, Marino Formenti, performed for two days for five hours a day, trying to work his way through this big sheaf of drawing/notations. Then, that sound was also recuperated into the system and redispersed, so there was this kind of densifying movement away, away from clarity. In a way it was like a negotiation, you could say, between a signal and what happens to a signal in a system.

The interesting thing about these systems around the Deathstar and some more recent ones is they’re actually not recording. They model the state of recording, the conditions of recording, and the apparatuses of recording, but everything is passing through, there’s no storage medium there. So periodically I had to go in and actually record if I wanted to keep something. They’re just kind of recursive systems ad infinitum. The volatility is sort of the subject matter in a funny way, there’s no “after that.” There’s no data necessarily being captured or something. These works sort of also model a kind of surveillance without the surveilled material being recuperated, except for occasionally as a kind of a marker or something like that.

The room was essentially empty. For that exhibition, I built two strange, piano-shaped tables and that’s it, plus cabling. Essentially, you’re really called upon to perform a kind of listening because your own sounds would also of course be returned through the system, a kind of hyper aware system.

BL: Would the visitor to Portikus meander or walk around the space? Would they lie down, or sit down? I know when I have seen sound installations, people do all kinds of funny things. But they often hunker down.

MR: As someone who came out of performance and then ended up making installation work, that’s a funny thing where you let go of control of what happens. I don’t really know. I’m there sometimes, I was there right in the beginning and then at the end of the exhibition, when Marino came and did the performances. Then people sat and listened raptly. But I think people ran the whole gamut of possible reactions, because one of the things that’s going on is a kind of complication, hopefully, of the idea of the listener.

In a sense, one might feel one has been kind of composed into the work, because there’s so much empty space in the sound. A lot of the sound is close to silence. But on the other hand, if you make a sound, you find that it’s coming back to you at a sort of uncanny temporal interval from one of the corners of the room or something, according to which microphone might’ve picked up what you did. I think it’s not at all clear, and I hope that it’s not clear what the visitor’s comportment and attitude and experience will be. That’s one of the things that interests me.

BL: This brings us right into another work, your Music Stands from 2019. I guess we could call the work sound sculpture, and we could call it installation. You’ve told me it’s a work that’s quite mobile and not dependent on a single architecture or a single space. Maybe we should say, just to describe it a little bit, that you created “a series of music stands.” They’re made out of steel and they’re very elegant, and the shapes are very fluid. They’re almost human height, some human’s height. Then, instead of a sheet of music, you’ve placed a sheet of aluminum onto which you very carefully etched a pattern. It’s not a flat sheet of aluminum, it’s kind of bumpy. These are very intriguing shapes, sculptural shapes. Do you want to say something about how you came up with the shape?

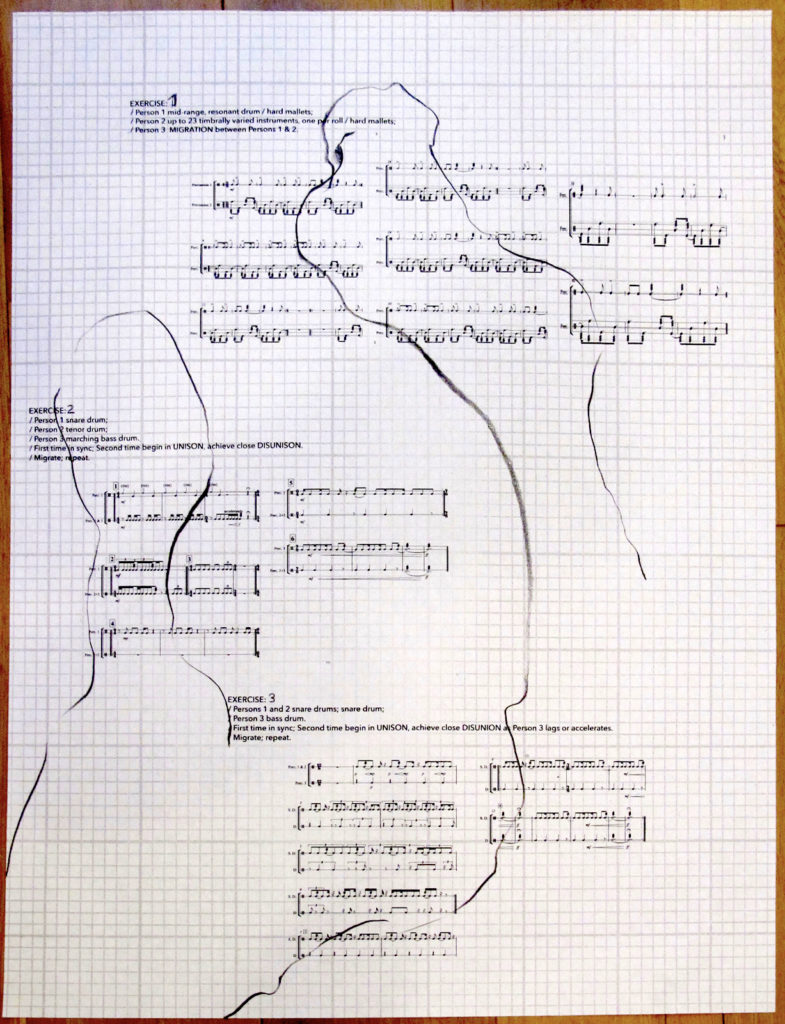

MR: I like your description a lot, thank you. The forms are steel rods and they’re welded and they sort of render in three dimensions. They follow some line drawings that I derived from the notations of a previous work entitled Free Exercise. It was another kind of orchestral performance, in which I organized military and civilian musicians in various floor patterns. I borrowed those line drawings when I was trying to think about, “Well, what shapes should these things be?” I realized that on my wall were these drawings that I had never really quite resolved. So, the first ones I made were modeled after these notation patterns. Sometimes they face toward a print, or sometimes some of them actually support a Dibond panel with an image on it, which are UV prints and they’re of small metal sculptures that I made.

I’m really interested in rethinking what we associate with the sensual, I guess, would be the word, the kind of different order of sensuality that has to do with a kind of different breakdown of where is the self. Or in the encounter between an object and a body, in a way who is the material? They’re body shaped and sized on purpose. They’re roughly speaking my height, which is average. But the materials are either reflective or absorptive in various specific configurations, so you can again move past these live microphones and hear the sound of yourself suddenly amplified, and the objects are performing that work. You are very much implicated in the whole kind of system of reflections and amplifications that are happening.

BL: This is similar to the Deathstar piece, your insulation that was at Portikus. With Music Stands you have clusters of dangling microphones that are placed in very particular ways, connected to the music stands. So instead of a musician playing in front of a music stand, here the microphone is picking up sounds in the space and sounds that you are generating. I know there’s a laptop, and software.

MR: It’s nice that we started our conversation by talking about the Sheer Frost Orchestra, and the kind of approach I took way back then to an instrument that I essentially didn’t know how to play and taught myself how to play wrong. I think you used the word DIY the other day when we were chatting. That DIY feeling is still something that I feel connected to. I am often using some software or some computerized elements, but I try to keep my sense of my entanglement with them. I try to balance the places where I have actually really developed a lot of expertise, but I am also really ready and willing to use things wrong.

The software that I’m using is really just ultimately to play sounds back or to build in little delays, to produce that kind of right-at-the-edge-of-feedback spin that I’m like really enamored of right now. It’s a kind of a balance between really engaging with what some of these machines can let us do experimentally, and also kind of keeping too much technical acumen at bay, which I think just becomes a little bit too much of a foregone conclusion. I’m not interested in that much control.

BL: I guess I should pose this as a question. There’s a lot of flexibility in being a media artist, which is what I could call you. I don’t really like definitions, because they always get changed. But in a way, you are a media artist. You’re a musician, a composer and a media artist. And there’s that DIY element. You have your studio at home where you work—you do a lot of drawing, you do a lot of writing and you work on the computer. Then there’s another element, which is you’re quite community based. You have an incredible network, not only as a teacher, but as an artist, as a composer. You’re connected to a network of people, including writers and others. How does that impact your creative process?

MR: Oh, that’s interesting. I’m really grateful for the experience I’ve had teaching at Bard all those years. I think I’ve been there for more than fifteen or maybe it’s seventeen years. I started teaching just a little bit and then eventually I became one of the two chairs of my program. So, I have a really beautiful network of former students, also current students. But I think in terms of populating my performance works and so on, and traveling and collaborating, the only thing that we haven’t really referenced in this conversation yet is my commitment to improvisation, as a practice. And as a person who had some formal training in composition, but it was not really [as important as] what happened to me through the experience of art school and people like Charles Gaines and Michael Asher, and those teachers at that time.

Then the discovery, around the time of creating the Sheer Frost Orchestra, that I could improvise. Improvising music using electronics, in my case, turntables and dubplates was, again, something I had to learn from scratch in my twenties. It means that you can kind of encounter people in a profound and totally contingent circumstantial space of exchange. So I would see my relation to community first through that lens. It’s not something I’m doing all the time now, but it’s so meaningful and it has been a really great privilege to sometimes have been able to just travel and encounter and really contend with people, and just go on stage with somebody.

BL: Maybe we’ll crash right now into the present. I think you’re an amazing artist.

MR: Thank you.

BL: It’s very exciting to work with you and to work with your Music Stands, which will be part of my ICI touring exhibition “Seeing Sound,” which was delayed by COVID. It was to have opened at the Kadist Foundation in San Francisco in July 2020, but will now open March 2021.

MR: I was supposed to have a big opening yesterday, also postponed! That show will open in May 2021 now, at the Kunsthaus Baselland in Basel, Switzerland.

BL: A few minutes ago, you said that you work alone in the studio. With this calamity, COVID-19, you’re working in solitude. I think there will be a richness that comes out of that.

MR: There have been peaks and valleys in my morale, let’s say. I think that I’m such a weird artist, probably: I don’t know how it came to be that I have the particular constellation of practices that I do. It’s tough right now because, for all the obvious reasons, but also a lot of the way that I work is thinking about presence. I don’t even know if I’m allowed to plan for co-presence in the near future. I realized that one of the ways that I can maybe start is to rethink some of what I’m doing in relation to the conditions we have right now, or that to compose will also differ in a sense. It’s a kind of a compartmentalization, or it’s separates the phases of a work into a kind of series of events.

I’ve been thinking, how would I compose distance or absence as a kind of quite natural outcome of the way I’ve worked until now, which has been so much about closeness and bodies coming into contact. This has to be on the horizon, but maybe there’s also some kinds of spatializations that are going to emerge that have to do with more emphasis on separation in time, like the space remains, but the simultaneity is in a whole new category, or something like that. I don’t have the answer yet. It’s too disconcerting, and I think we’re all in this slight shock in a way, for now. I don’t want to get there too quickly either.

BL: On behalf of Marina Rosenfeld, thanks for joining us for this episode of “Barbra London Calling.”

—

Support for Barbara London Calling is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and Independent Curators International in conjunction with their upcoming exhibition, “Seeing Sound,” curated by Barbara London.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram @Barbara_London_Calling and check out BarbaraLondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Bower Blue , with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded May 11, 2020; it has been edited for length and clarity. All photos courtesy of the artist.

Images & Video

Rosenfeld often cites her earliest work, the scored performance Sheer Frost Orchestra (1993), for seventeen women seated on the floor in a single sixty-foot line, each playing an electric guitar, as formative. Performers in this piece, first enacted during her graduate-school days in Los Angeles, were directed and learned to “play” their guitars using only nail polish bottles to touch the amplified strings of the instruments in a series of choreographed actions– “drop, hop, drone, slide, scratch and A for anything or anarchy.” The work instantiated many of the strands that would characterize her work going forward: a re-weighting of process over outcome, a fascination with the contours of sound fields produced by unorthodox staging, and a foregrounding of audio diffusion itself (PAs, amps, the technical-sculptural register of objects) as means of modeling flows of power and emergent forms of sociality.

Rosenfeld’s work seems to sit just outside of category—a hybrid practice only partially accounted for by “sound art.” She has seemed to use the notion of the composer equally as a screen and as a sometimes contrarian mode of thinking through and embracing the complexity of situations, sites and forms. She has described her process as an intervention or postponement inside the unfolding process by which what we know as music exerts its formal, rationalizing identity. As such, her interventions are also often highly formalized, featuring networks of gesture, amplification and imagistic representation; as much by suggestion as by concrete example, her works offer a phantom image or aftersound of the possibility of arresting the otherwise unimpeded flow of signification in what she has sometimes called “the musical situation.”

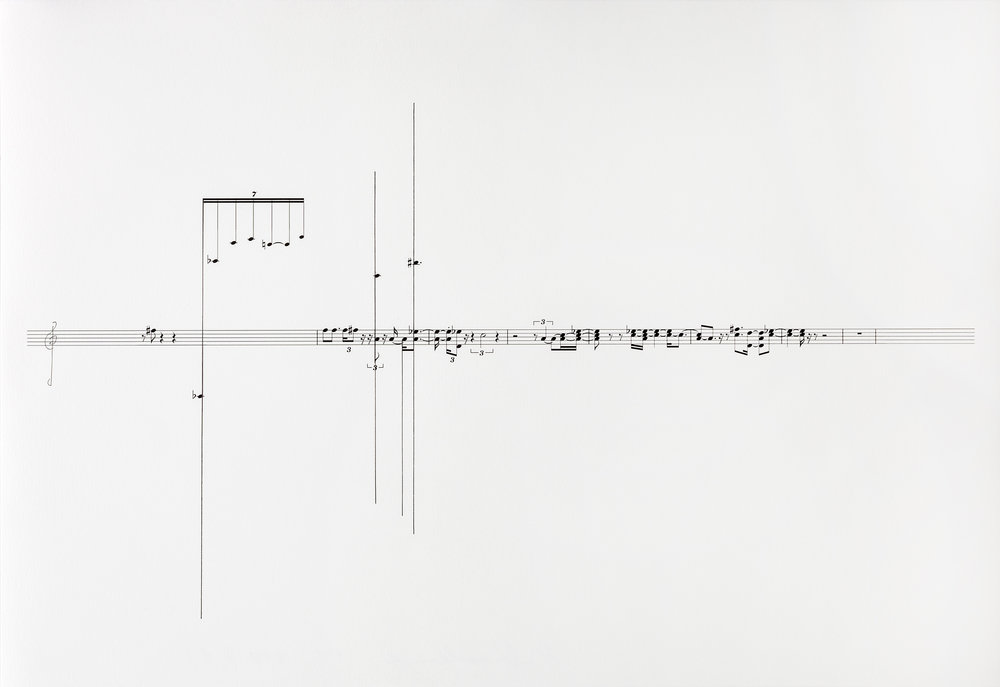

WHITE LINES (2003)

Deathstar explores the idea of a controlled production of feedback and distortion in a site as a means of producing a generative or continuous state of composition. The work was first mounted as a sound installation at Portikus Kunsthall in Frankfurt in 2017. In the tower-like architecture of the gallery, Rosenfeld hung a multi-microphone bearing seven microphones. From the recordings that were generated within the recursive and volatile environment of the gallery—substantial periods of spectrally complex room tone punctuated by fragmentary eruptions of musical sounds (voice, piano, noise)—she generated a large body of hand-drawn, computer-enhanced notations. These were displayed in booklets as part of the exhibition, and performed during its last week by the virtuoso pianist, Marino Formenti. The installation, starting two weeks before opening to the public, was structured to continuously listen and play back a sound score as sounds entered the gallery from loudspeakers in four corners at floor level. High overhead, the microphone array received these sounds and returned them to said loudspeakers at a slight delay (+/- 13 seconds). At any given time, a recorded sequence would thus capture the room and its reflections, doublings and triplings, and often acute timbral distortions. The notations introduced vertical lines (to be performed as clusters) bisecting known pitches wherever instances of resonance exceeded the capacity of conventional notation. The pianist was free to transpose and circle back, in imitation of the site’s own distortions. A second transcription from Formenti’s performances lead to Deathstar Orchestration, a concert for orchestra and solo piano, which was premiered by Ensemble MusikFabirk at Donaueschingen Musiktage festival in 2017. Subsequent transformations and distortions of the same material have led to further versions and the recently released double LP Deathstar by Shelter Press.

Rosenfeld’s Music Stands are metal armatures that support constellations of microphones, loudspeakers and reflective photographic panels that baffle and modulate sounds as they are released into the gallery. Derived from notations and trace-like recordings, the work’s combination of visual and aural cues—deformed and folded shapes, the artist’s voice, momentary eruptions of noise—operates on the verge of feedback, amplifying themselves as well as the bodily presences of visitors. Rosenfeld’s own voice is prominent in the soundtrack, “registering both the artist’s body and its absence and replacement by an electronic, dysmorphic surrogate.”

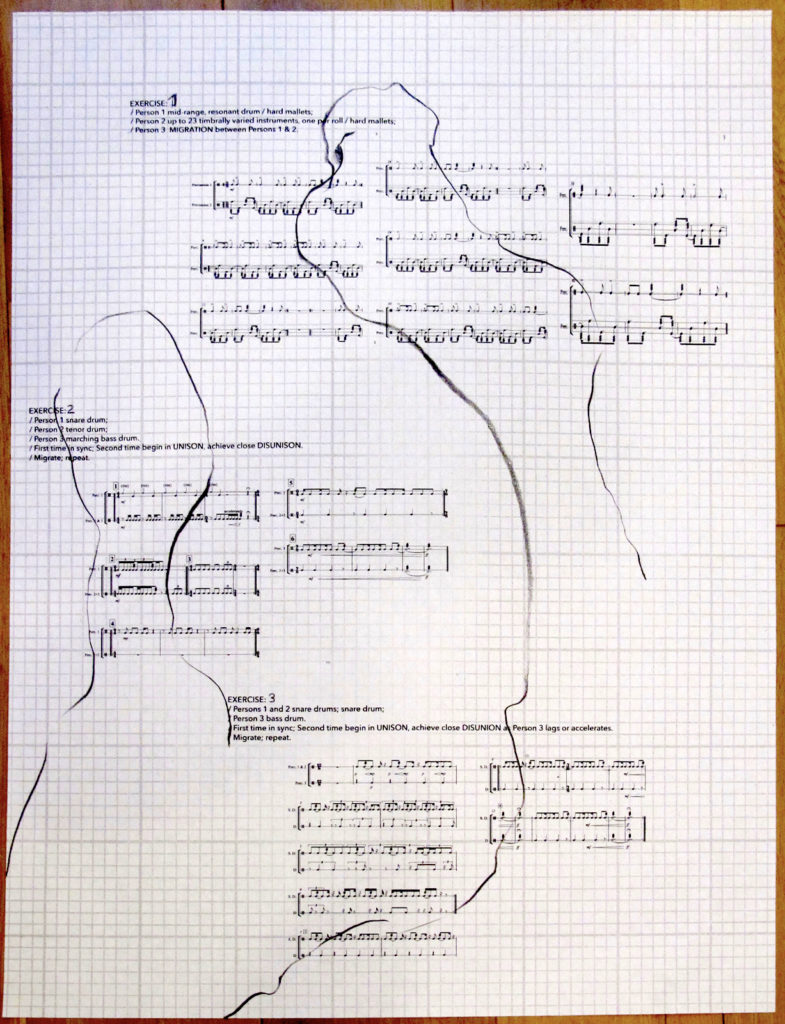

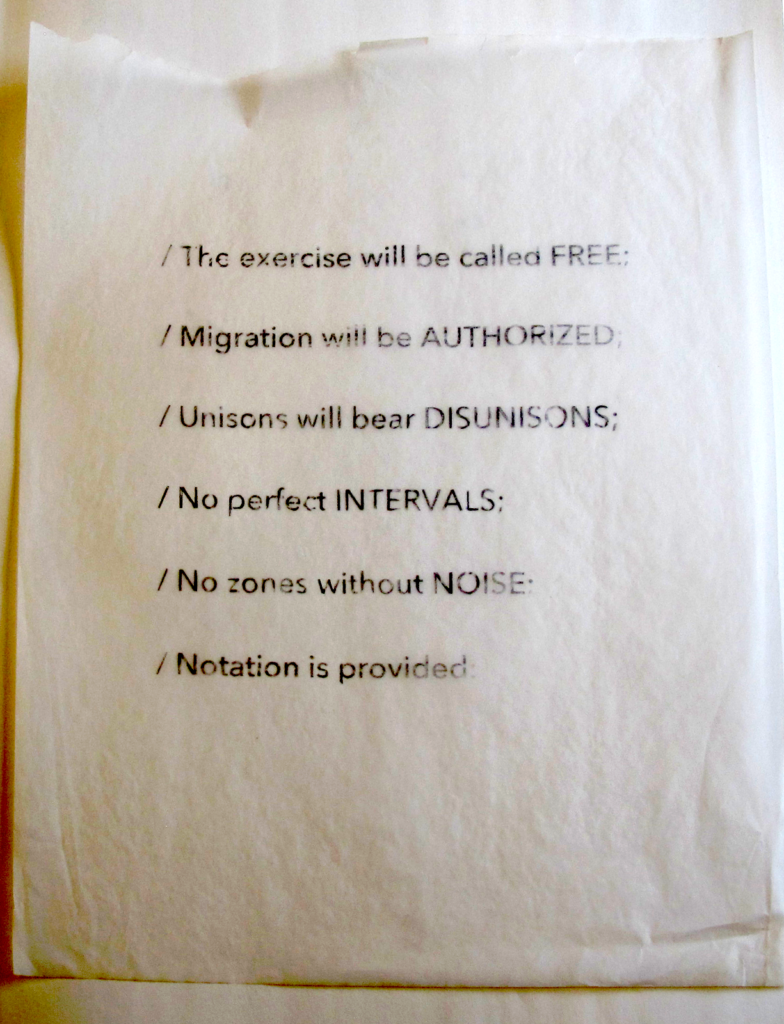

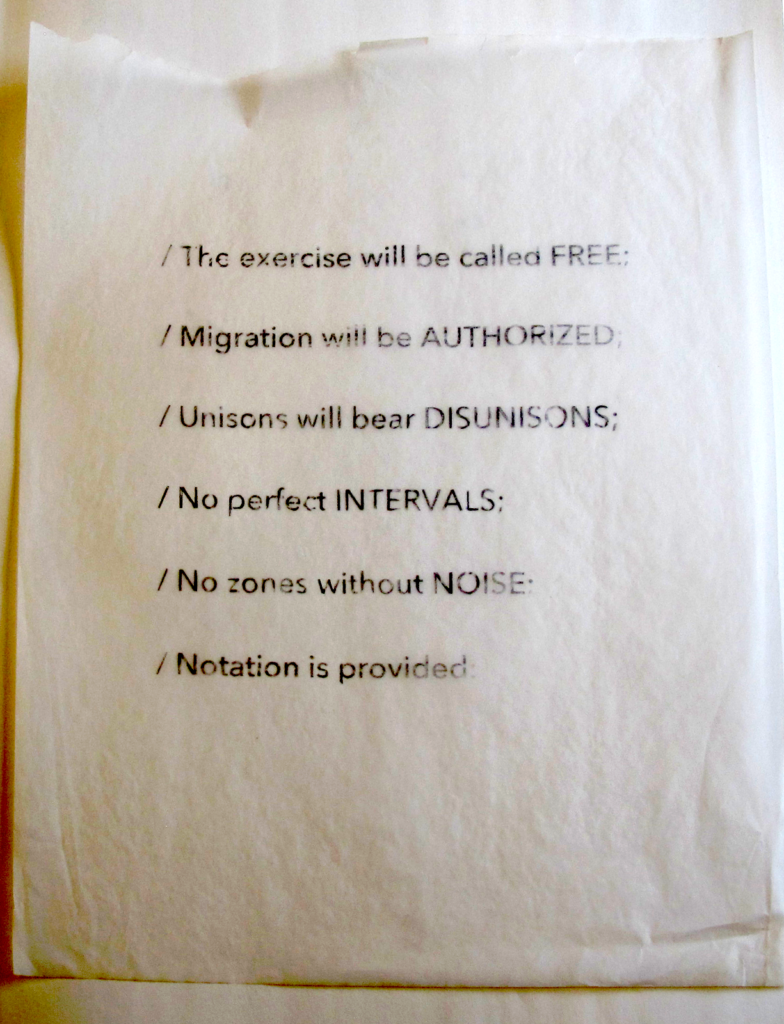

Free Exercise is a performance/installation for enlisted military and (civilian) experimental musicians who carry out a series of “exercises” of various degrees of physicality together. It was first mounted at Bergen Kunsthall (Norway) in 2014; an expanded version was mounted for the Biennale de Montréal in 2016 at the Regiment de Maisonneuve, a Quebecois military armory, and the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art. The work calls on musicians to stage a series of rhythmic and choreographic relations, taking up different formations and arrangements, and performing original music in unison and in what the artist has called “dis-unions”: a procedural prying apart of complex rhythmic unisons into cloud-like structures of duplication and temporal distortion. Together and apart, musicians navigate and overlap the institutional architectures of the museum and the military site, probing patterns of cooperation and conflict.

Ssalute is a work Rosenfeld created for Dallas, Texas’s Aurora Biennial in response to the conditions of the Covid era. Occupying the upper floors of a parking structure in downtown Dallas, Ssalute conceived of the spectator as a driver, who could safely navigate the work while enclosed in the protective skin of their vehicle. As drivers wound their way up the labyrinthine architecture of the empty car park, they encountered a trumpet player, whose thickly amplified and augmented trumpet salutation followed them, until they emerged onto the roof and the ambient sound of the city. In two locations, passersby may have already encountered an image of Ssalute in the form of a billboard, suggesting a visual form to the experience that left space equally for presence, intimacy and alienation. Substituting the vacant car park and its radical acoustic treatment for actual civic gathering space, Rosenfeld’s work was an enigmatic public proposal in a time of widespread isolation.