Today I’m calling Jonathas de Andrade. Born in 1982, Jonathas lives in Recife, on the northeastern coast of Brazil, where he works across video and photography with an interest in how language can render truths as well as untruths, and how that same language can liberate or marginalize its subjects.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Jonathas, thank you so much for joining me.

Jonathas de Andrade: Hey, Barbara. Thanks a lot. Thanks for the invitation.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: You’ve lived your adult life in Recife, a vibrant Brazilian city rich with cultural history and a strong film industry. The city is marked by what you have called “a rural parallel civilization that coexists in the proto-urban Recife of a super under-developing Brazil.” There’s also a vibrant music scene. Was music a big part of your upbringing?

JdA: Yes, Recife is a very strong place that captured me. I came to Recife to study social communications. I was born in Maceio and went to south Brazil for two years and studied law, not sure where my career would go. There was already an interest in social concerns in general, in politics, and in how people in communities engage to make their living within a world full of injustice, full of the privileged and the unprivileged, and that only grew. So themes around race, class, and the city always interested me, but [combined] with the power of the image, with the power of creating ways of telling stories.

I quickly got closer to cinema. Even while studying law, I started attending classes in cinema school, in art school, as a listener. Then I realized my law career wouldn’t work, so I quit law school. I decided to study social communications in the city of Recife, which is a large city in the region of the northeast, where Brazil started to be colonized by the Portuguese.

It’s a region very much rooted in this past—and with all the scars of that. We can see the ruins, we can see a mixed people, very strongly marked by the traces of postcolonialism, of racism post-slavery. This heavy and culturally dense situation—also heavy politically and socially—creates a very intense environment in terms of culture. As you mentioned, there is a huge scene in music and in cinema; it’s a very complex place to be, but very inspiring.

I came here in 2002 and decided to stay, although my plan was to just finish university and then go somewhere else. But the city captured me. Being an artist in the contemporary art field, I found myself working a lot with photography, with cinema, motivated by the issues that this place would condense. I started to develop my first projects here, and it made sense to continue. I thought they would gather some of the aspects that I was interested in speaking about. My first projects already created an initial guideline.

BL: I’ve never been to your city, although I’ve been to São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro several times. But because I worked originally with artists’ books at MOMA, I came across the work of Paulo Bruscky (b. 1949). This older Recife artist is known for his very active role in the mail art movement. Did he have any influence on you, or did you know him? Or is mail art another world?

JdA: Yes, yes, Paulo Bruscky is a very interesting figure. He was around while I was studying, and I visited him a couple of times. I’d heard of him here and there, in conversations with other artists. Through him and through other artists of his generation, like Daniel Santiago (b. 1939), I got to know the spontaneous practice of doing performance, then collage, and the small actions in daily life.

This spontaneity and freedom inspired me, and to see contemporary art as something that could be anything. It could be an intervention in the newspaper, it could be going to the open square and performing an act, engaging people passing by. This freedom, and the idea of art being something that could be done outside the institution or a formal museum, was something that definitely inspired me to understand contemporary art practice as something beyond the big institutions, and to be absolutely free.

If I was unsure initially whether I would go to law school or turn to history, to filmmaking, to photography, or to research, contemporary art was something in which I could combine them all. My projects started to be a sort of collage of these interests, which, if isolated, couldn’t live by themselves.

The videos I started doing had a strategy of their own. I would sometimes decide a point of departure: put out an open call to people or form a narrative structure to explore or determine a way of photographing that then would become a video. Each would point to that one aspect, then I would create a strategy to go after it. This re-imagination of methodology was something that pleased me a lot, and I think it’s very dear to me to keep it alive—the interest in art and not settling down in only one way of doing it. Especially with the lack of commercial structure in Recife, where there are very few galleries. The museums always suffer from an unstable budget, so artists have to gather themselves and create access by themselves. I think this taught me to try somehow to create my own way of making my projects exist, and also be directed towards the audience in an inventive way. I would always have to think that I might not have a museum or gallery to make that work exist.

BL: Let’s now dive into a particular work. Let’s start with Pacifico, your twelve-minute work from 2010. You shot in Super 8 and transferred to HD. You created what we see in Pacifico by using very humble materials: Styrofoam, model board, paper, maps, and simple animation to render a ferocious earthquake that erupts over the Andes, detaching Chile from the South American continent. As a result, Bolivia regains its lost coastline, Argentina gains coast on both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, and Chile becomes a floating island, adrift in the sea. I’m curious, why did you focus on cartography in Chilean and Bolivian history?

Photo: Courtesy the artist

JdA: That work began in 2009, when I traveled for seven months around South America. Being Brazilian is very particular; we speak Portuguese, while the rest of South America speaks Spanish. That makes the Brazilian self-conscious, and a little bit distanced from the rest of the continent. We are facing toward the Atlantic, not the Pacific. We don’t exchange many cultural products with our neighboring countries as much as they do, because they produce in Spanish, and that makes a difference in the end.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

I was always curious or disturbed by the fact that we were Latin Americans, but there wasn’t a self-awareness of that. This project started as a trip of recognition, as if there was an echo of the dictatorships that set us apart from this continental unity. My idea was to travel around a few countries, learn Spanish finally, and try to make the exercise of behaving—even if it was fictional in the beginning—as a Latin American. I would get the awareness of an identity that I definitely was, but was not aware of as I was not brought up like that. My exercise was to look at the countries’ histories as if they were also mine, and play with them, and authorize myself to try some exercises while there.

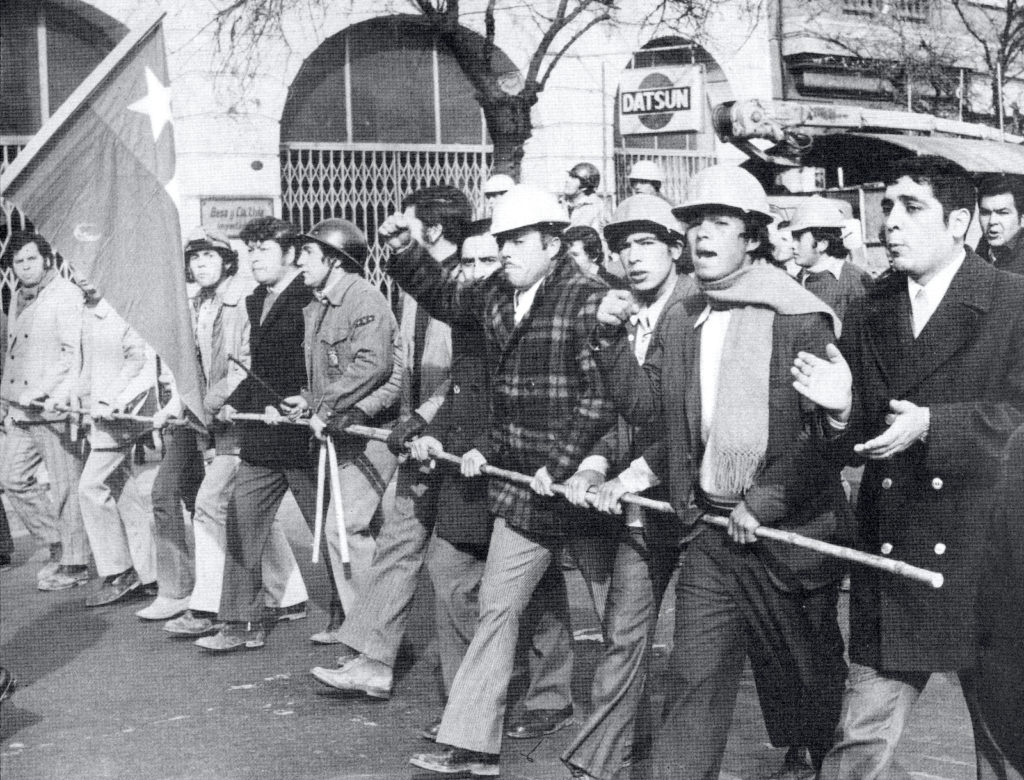

In Chile, I observed that the dictatorship was very harsh, and there was a particular alignment of Chile with the neoliberal agenda worldwide. And then there was a feeling of isolation, which made me think of the recurrent earthquakes that the country historically has had. What if there were an earthquake that separated the entire strip of land and set the country apart? That illusion was an excuse for me to get back to imagery of the dictatorship, and not locate it exactly in time, but as if we were facing a sort of a traumatic flashback; so, the images were puzzling for the mind, but they speak of a yesterday, which is also present.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

It’s very intense to remember about this work, particularly, because here in Brazil we have at the moment a very, how do I say, a crazy President, which somehow is very apologetic to the dictatorship, very sympathetic to it. It’s a particularly harsh moment in Brazil right now, and it speaks of that dictatorship, which is never over, exactly. It comes as a wave, recalling the tension, recalling strong echoes.

The Pacifico video had to do with that. But it had no idea about this past, this memory that it’s never overcome and would definitely be something that Brazil would relive in a very near future.

BL: Another work of yours from 2010, and maybe the result of that journey you took, is 4000 Shots. I gather it was originally sixty minutes long, shot in Super 8, and displayed as a loop. You recorded, one by one, the random faces of anonymous men, who looked at you and at your camera as they walked along the streets of Buenos Aires. The film moves faster and faster, and the tension builds. What was the audio?

JdA: The audio was built by me in the editing. I shot frame by frame in Super 8; then in the editing, every minute one second freezes on a random face. The sound that goes faster creates this tension, and then it freezes in a sound of an abrupt shock, as the video freezes as one single image.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

These are faces of men in Buenos Aires. I was trying to get closer to the iconography of the people who disappeared during the dictatorships in South America. Then it was very common to see similar black and white images of the people who disappeared.

There was also an approach toward a violent masculinity that I started to get closer to in this piece. That was the decision to portray only men, which was also to get closer to this desire, this homoerotic desire. It was very much cursed historically, cursed by a dictatorship that very much also targeted this kind of random persecution.

It was a very small detail that I tried to experiment with myself, [to figure out] how it would be to pursue these images from the street. Also, I wanted to see what would be the reactions of people when they noticed they were being photographed, in a sort of looting of their images. They were just passing by, and then would notice someone taking their photo with a vintage camera. That was in 2009, when people didn’t have mobile phones with cameras built in. So, it was another exercise.

It’s interesting now that eleven or twelve years have gone by, this exercise today would be something different today. It’s very interesting to understand the temperature of the videos, because strategies change from time to time. As I work a lot with ambiguous feelings, it’s very funny to see how an artwork sometimes is perceived in one way, and then a few years later, it would be something else, or changed slightly. That’s something that I’m starting to notice. I started producing work in 2008, and now I get a little bit of distance, and 4000 shots is one of these cases.

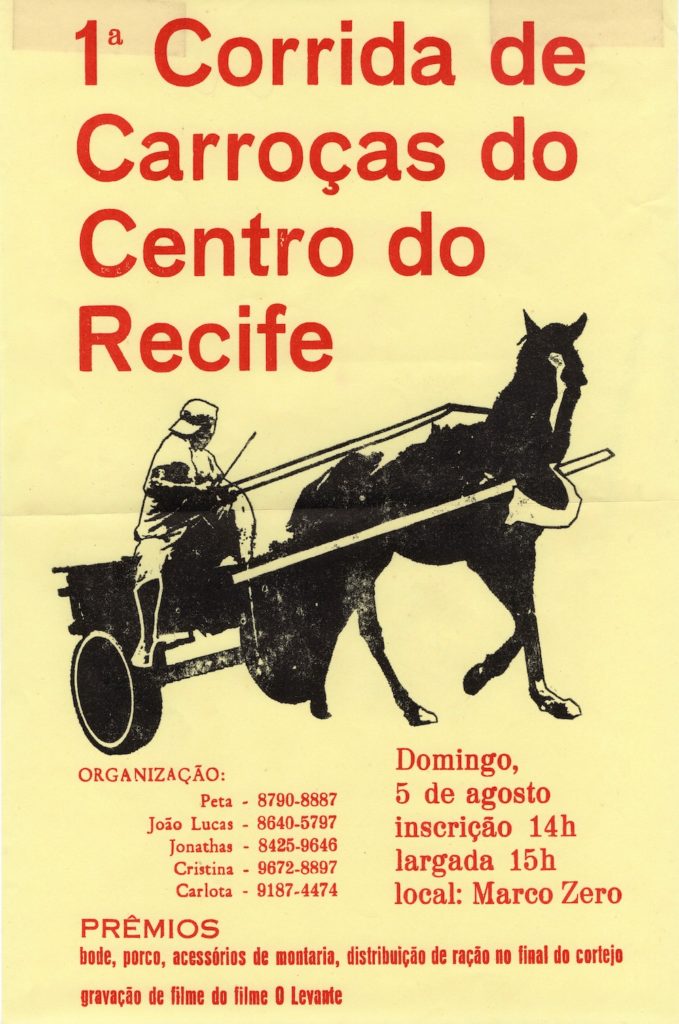

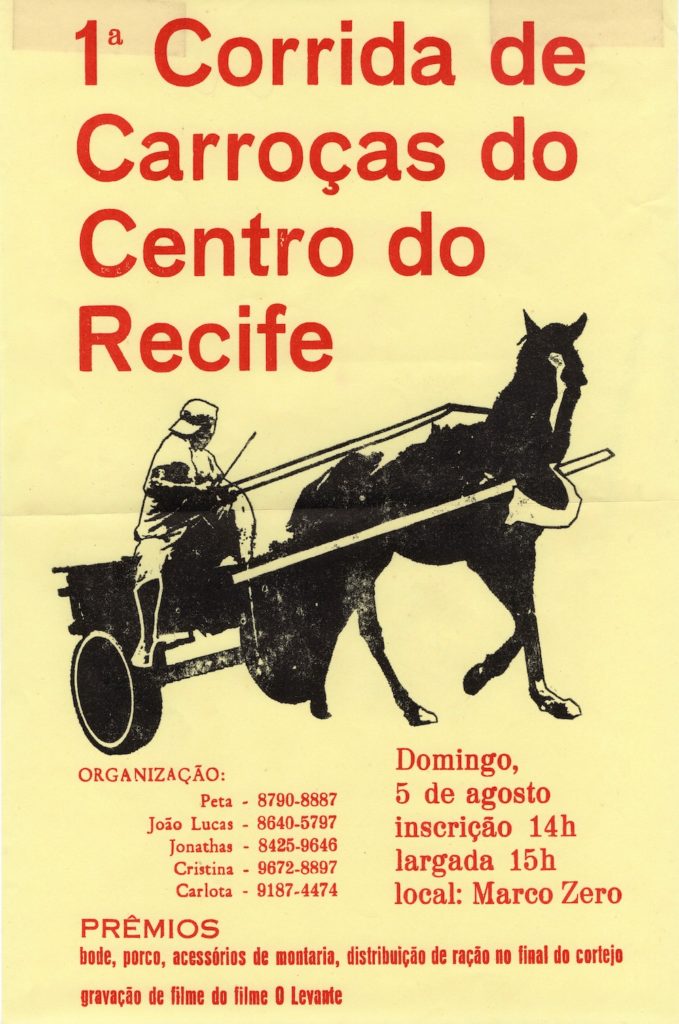

BL: I’m going to jump forward a couple of years to O Levante from 2012-2013. Please excuse my pronunciation. When I first saw the work, I was really bowled over by the energy and by your use of language. It’s an eight-minute video featuring over fifty horsemen, each in their own cart, storming through the streets of downtown Recife. You staged the first ever horse-drawn cart race in the center of the city, with goats given out as prizes to ten winners. Is it true that you were able to stage the race by asking the authorities for a permit to make a film?

Photo: Courtesy the artist

JdA: Yes. It was a very crazy project, one of the craziest things I ever organized or thought about, and it was so fundamental. The initial idea started when I realized how fascinated I was by the presence of carters with horses on the streets in the middle of a city that was primarily urban. The presence of horses and carters would make me think that they were a rural presence in the city. They were sort of a rural trace of the region’s past. We had a cycle of plantations producing sugar cane, which was the major economy of the region. In the beginning of Brazilian colonization, this was the big wealth, with a complex landscape of slavery, of indigenous people being killed or forced to work. To me, these complexities remain very clearly in the majority of the population, people who are poor and who have Black and indigenous ancestry.

Although the legislation, the law, forbids the presence of carts on the street, because it’s understood that the city is entirely urban, not rural. This law existed, but still people had no other choice. They work with the horses; it’s the way they would transport goods into the city and it’s their means of transportation. For me, it was a very strong act of understanding the law, one not made for the people, but limiting their life within this prohibition. For me that was a very brave act. Also, the law would make them invisible. The law would totally ignore them; you see the law is very clearly made for the elite.

When I realized that, I would often see one or another carter going along the avenues; for me, that was a marvelous scene of braveness, of resistance. I started to imagine that, if they are invisible when seen one-by-one, what if they were seen together as a crowd, as if they were a parade? Out of nowhere they would arrive together, all the carters driving along one road as a bold act. When this delirious poetic happening started to appear in my imagination, I would just smile.

Then I heard about a new law being written and was about to be approved. It would authorize the Recife government not only to forbid but to approach the carters, arrest them, and drive them out, restricting them to the countryside. This law was based on the suffering of animals and it was very cynical. Definitely the suffering of animals is a very urgent and very important case; however, the law was not about the caring of animals, because if it were, it would be applied with penalties, and there would be an educational program on how to treat the animals better. But if you arrest someone who has a horse and leave this person in the countryside, the mistreatment of animals will continue if there are no other actions involved. For me, it was very clearly about a hygienization of the city, a social hygienization of the city, because it was 2012 and there was the World Cup, a phantom that was present. The talk was all about the Olympics. Brazil was experiencing an economic boom and a lot of attention was on Brazil. And so, Recife should be cleaned up. The whole point wasn’t about shaking things up and giving possibilities to these people so they would engage better in the economic chain, but was just to set them apart as a poor and brown, Black, mixed crowd.

It was super hardcore, and my idea was: Okay, if this government is dealing with this situation like that, how could I make this scene possible, if it was something prohibited? I started to ask permission to shoot a film that had a scene of a horse race. Being that it was fiction, it was very hard but I got the permission. For the carters, I announced that a horse race would take place so that a film would be shot. Basically, it was the same thing understood from different perspectives.

I had meetings with many departments of the Mayor’s office—the Cultural Department, the Traffic and Roads Department, the Sanitary Department, and everyone engaged to support the film. Afterwards, this was O Levante, The Uprising.

I invited fifteen filmmakers from Recife, from this vibrant scene that we have in Recife. They stood in different spots from which I planned the race and the parade to happen. It was one of the craziest days of my life, because the carters took a long time to gather. All of the communication was done through pamphlets. I didn’t use social media because it could attract the wrong attention, like having TV reporters, and then maybe the film could not have happened.

I went to the exchange markets, assessorias [markets] for horses, that this group of people [the carters] usually would go on Wednesdays and Saturdays. I started to work on pamphleting with my crew there.

The carters took more than one hour to assemble, beyond the planned time for them to start arriving. It was insane because at that point, I imagined, okay, no one is coming. Everyone was looking at me. I had a huge team, police guys ready to stop the traffic for the scene to happen, and they were saying, “Where are the actors?” And I say, “Okay they are coming.” And then I was so nervous. Then I realized, oh my God, it was a huge frenzy. But they started coming, fifteen here, fifteen there, going to other places. Around fifty carters with their families showed up. It was a massive crowd, something I had never experienced.

I had a loudspeaker in my hands, and I didn’t know how to use one. I would say out loud, “Let’s organize here,” and of course, no one would respond because it was a different code, a different protocol for them. Then the police said, if we don’t do it now, we have to cancel. So, I asked the help of one of the men on a horse. Once someone leads, everyone follows, and the thing happened. I became part of the crowd instead of being the author, or someone who created, someone who was guiding. I became part of the mass, and that was beautiful. The thing had a life of its own. I did the open call, but once the thing was there, it had like its own peculiar life, and its own heart, and that was quite a lesson for me.

When I got the footage, it was insanely chaotic. I took one year to really breathe and have the relief of not having had accidents during the event, which was one of the challenges and one of the risks. I had to sign contracts with the Mayor, and with the supporters. This project was supported by the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, and I had to really commit to being responsible for everything that happened. I was super nervous. It took me one year to arrive at the final edit of the video.

I realize that I mentioned having a project, which is not only the video. It’s the video, it’s the event, the happening itself, the process of doing it; I also worked on a documentation of photographs, and the plan of the work as an installation. The art is not only what we see in the museum, but how it develops.

It was quite a lesson for me. At the point when I was about to edit the film, my internal feeling was that something had already happened, and that definitely was the core of that project. Something definitely was very astonishing. Then here and there I had people saying, “Ah, so that crazy horse crowd that I saw back in 2012, that was you behind that?” And I said, “I was involved, yeah.” That was major for me, and that was quite something.

BL: One way you pulled the video together was, I believe, you worked with what’s called an aboiador. Perhaps you could say a little about this type of traditional singer who narrates the work?

JdA: The aboiador is one type of singer from the countryside, one that improvises verses based on the experience of the countryside, of the plantations, of the cattle. The aboiador improvises on the tough life of the countryside, of the humble men and women.

This aboiador, Jerome, showed up on the day of the horse race. He started singing out loud about what he saw in the moment, and combined those images of the countryside repertoire, like the horses and the carts, with the elements of the city, the bridges and the beauty he saw. It was super interesting.

They have this culture of being challenged by a theme, and they improvise. I took his phone number and later I invited him over to the studio, and I challenged him to understand that day as a revolution of the carters, of the countryside within the city. The video, The Uprising, begins with our conversation. I recorded our conversation, and then he started improvising on that, singing for four hours. Half of the video is carried along with his verses, which speak about his poetic understanding of a revolution, and the harsh life of the countryside men, and the city.

At the end of The Uprising video, I invited a narrator to read a text that I wrote, which is a sort of manifesto around the issues of gentrification and the city, and the city which is free and welcoming, but also very much divided.

BL: Let’s move on to your work of 2016. The Brazilian filmmaker Joaquim Pedro de Andrade has been described as a true tropicalist. We’ve already been talking a little bit about that. With your two-channeled work O Caiseiro (The Housekeeper), you’re in dialogue with de Andrade’s 1959 film, O Mestre de Apipucos. You present his film on the left, which is juxtaposed with yours on the right. You touched on it but let’s go maybe further into what the term tropicalist means, and why you reference Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s work in this piece.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

JdA: Joaquim Pedro de Andrade was a great filmmaker. He made one of the great Brazilian films, Macunaima, which I recommend a lot. But then I engaged with this other piece, the first film he did in his career as a young filmmaker. He made a small report on Gilberto Freyre, the Brazilian sociologist who in the thirties wrote the book, Casa-Grande & Senzala (The Masters and the Slaves). Joaquim Pedro de Andrade records Freyre, films his daily routines over one day.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

It’s very interesting because Gilberto Freyre is a very controversial figure for having written this book, Casa-Grande & Senzala, which speaks of how the Brazilian racial mix was born in the mix of the Portuguese colonizer, the indigenous native people, and the enslaved Africans that were brought here. He’s criticized and reviewed a lot, because, although his theory in the book makes advances for being a theory from Brazil itself about the Brazilian mix, he is criticized for being too romantic, as if it’s a history of a gentle mix that created a sort of racial democracy.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Of course, this is not true. It’s more and more explicit, because we have a very racist Brazil. The police violence here is brutal, and it’s mostly targeted in Black communities; and the population in prisons, is majorly Black men. The segregation that happens seems to be very subtle, but it’s not. The possibilities in Brazil for achievement, access to jobs, education, possibilities primarily for privileged white people. But in daily life, you could read by mistake, as if it was too gentle.

So, my piece O Caseiro combines a film made in 1959 by Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, picturing Gilberto Freyre in his house, a big house with servants that he calls by their names. He is shown at breakfast with his wife, served by a Black man. He gently gives approving thoughts to the cook. And I create a second screen with footage I shot, where a housekeeper, a fictional one, lives in the same house today, and he is the protagonist.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

That’s the basic idea of the video. These two screens were synchronized in the editing. It makes us look back. especially in relation to the present, a moment when the Black community is carrying the discussion very much along, like is happening in the States with the recent events, such as the death of George Floyd. This has an echo in Brazil. I think this video makes us look into very harsh events and at racism in Brazil, that makes us also rethink Latin America.

BL: Perhaps we move on to your work from the same time period, your 2016 work, O Peixe. I tried to get the correct pronunciation… You shot O Peixe (The Fish) in 16 mm, and transferred it to HD. It’s visually stunning, and is a very complex production. The work unfolds as one after the other, ten very strong fishermen, kind of ruthlessly and very carefully, each in his own way, moves his boat to what is a beautiful river location, and prepares his tools. It could be a net, a single line of nylon with a hook, or a harpoon. Each casts his net or line into the water, and waits very calmly, and then reels in a fish. Then with the fish that they’ve just caught, each enacts a very tender ritual of embracing it, much the same way one might embrace a lover.

The work is also very sonic. We hear the splashing of water on the boat, the swishing of the breeze, the flapping of the fish against the floor of the boat. I’m curious, in your practice, do you consider sound and image to be equal? Do you prioritize one over the other?

JdA: This particular piece, O Peixe, was the moment when I understood the power of sound in video making, in filmmaking. It was my first experience of working with a Foley artist, Mauricio d’Orey.

I wanted to create something that was both fiction and non-fiction. The borderline between documentation and real fiction is a major interest of mine. For O Peixe, I invited a group of real fishermen to perform this action, which I created in my mind. It was to have a group of fishermen carry out a ritual of embracing with their bodies a just caught fish, as if they were asking to be excused, for they were following the fish to its death, out of their own needs to survive ,. It was a very ambiguous image, because I wanted it to be loving, although it was extremely violent, and it’s extremely naturalized.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

In our daily life, we do eat animals’ flesh, and there is a huge discussion about that. We are facing the collapse of nature, through the transformation of humanity. At this point, we are really starting to feel the major consequences of that; but also we are trying to review our ethical boundaries. At the same time, we realize that big companies are the ones who really lead in these decisions and these actions. So, it’s a super complex film, and I wanted this poetic loving gesture to shake these emotions, which are very much in the air right now.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

It’s an action without words; the fishermen don’t say anything, and the film doesn’t have any narration. Sound plays a very important role of moving the audience towards the psychological level of the scenes. While editing, for me it became more and more clear. I had no idea when I started this project that sound would be so important. When we have an immersive presentation of O Peixe with 5.1 surround sound, I have seen the audience really get immersed in the experience of the film.

The ten different fishermen are shown performing the same act but slightly differently, because everyone is somewhat different. The piece is very emotional, and I think I started with this tugging at my mind. I thought I had a clear idea, but when I started shooting, I realized it was very violent, and that came back to me, how I was emotionally very charged. I felt responsible, and I felt strange because of the violence of the death. Then I realized that was what the piece was about, to bring this emotional level to this discussion that is usually undertaken from a certain distance.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

It’s fiction if you understand that as a ritual, which it’s not. But it’s documentary, when you understand these fishermen have never embraced a fish in their life. There was no rehearsal, so the scene you see in the film is actually the first time that fisherman embraced a fish. So, it’s very documentary as well.

The camera plays its role and captures the beauty, not the eroticism that was in the air. These fishermen work within nature. It’s very warm, so they work with their shirts off. Also, the camera goes in closer to the fishermen, as if it were devouring the fisherman as much as he is devouring the fish.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

It’s the moment where I experienced working with a film crew, which had experience with this type of structure. That allowed me to get closer to the real act of talking to the fishermen instead of producing the whole thing. That was also very important to understand the type of result we reached, with one setup which is more spontaneous, and another one which is more controlled, and having the expertise of a crew that works with that. So it’s different. It was a moment where I tried something else.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

And now, the world is upside down, no? Basically, like most of us, I’m trying to figure out what’s next. It’s a moment of reviewing ideas, sketchbooks, and collections of things, documents, scratches, ideas, and trying to understand what’s relevant, not only to the moment, but also what’s relevant to my own personal heart in relation to what we are living, no? Everything is very … how do I say this in English … very much alert, no? And we have authoritarian governments, we have uprisings—silent uprisings and outspoken uprisings going on. What’s the role of art and poetics in the middle of that? Keeping ourselves alive but also alive in the dreams. So I try playing a lot with the things that are in the air, which are clearly here, but sometimes not spoken about in the same way. I’m scratching ideas, but I’m taking this moment as a way of also reviewing my practice and taking a little break to understand what could be a nice next step.

BL: I can’t wait to see what’s next. Now my very last question, which I’m asking everyone who’s part of the series. Do you consider yourself a media artist?

JdA: Wow. I don’t know exactly what label I would say. For me, what interests me in the artistic fields is the possibility of being a little bit of a chameleon. Using video that flirts with cinema, that flirts with photography, that flirts with sound. Sometimes I get away from the moving image to create a moving image within a series of photographs, and sometimes I engage with text.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

But even when I do so, I hear close friends say that I do photo installations very cinematically. My engagement with narrative and moving image, I think it’s beyond what we understand as projection with sound and video. I think it spreads all over. I think that’s the cool experimentation to do, to really play on that. That’s what I hope, actually, to have fun with this experimentation. Reinvent and really do that with enjoyment, because that’s how I experience the audience really engaging back and giving great responses that make me move forward in my research and in my practice.

BL: Thank you so much for taking the time today.

JdA: It was a great conversation, Barbara. Thank you very much.

—

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram @Barbara_London_Calling and check out BarbaraLondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Bower Blue , with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded June 24, 2020; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Images & Video

Born 1982 in Maceió, Brazil, Jonathas de Andrade lives on the northeastern coast of Brazil in Recife, where he studied social communications at the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. He works across sculpture and installation, video and photography, with an interest in how language can render truths as well as untruths, and how that same language can liberate or marginalize its subjects and even its users.

With the artist Cristiano Lenhardt and other friends based in Recife—the designer Priscila Gonzada, the architect Cristina Gouvea, and Silvan Kaelin—he co-founded the collective A Casa como Convém (The House as It Should Be) in 2007. Together the group would gather a small group of local and visiting artists in their house and studio. Over ten years, the group focused on issues surrounding tropical modern architecture, offering a counterpoint to the dominant cultural axis of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Using such humble materials as Styrofoam model board, paper, maps and simple animation, the artist created a ferocious earthquake that erupts over the Andes, detaching Chile from the South American continent. As a result, Bolivia regains its lost coastline, Argentina gains coasts with both the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans, and Chile becomes a floating island adrift in the South Pacific Ocean.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

De Andrade recorded individual faces of anonymous men who glanced at him and at his camera as they purposefully walked along the streets of Buenos Aires. They move towards the artist and pass him by. Tension builds as the film’s pace moves faster and faster.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

The artist staged the first-ever horse-drawn cart race in the center of Recife, with goats given out as prizes to ten winners. The work features around fifty horsemen, each in his own cart and accompanied by friends and family, storming through the streets of downtown Recife, encouraged by a spontaneous audience that grew to nearly four hundred people. Having obtained an official permit to make a movie, the artist managed to create a political work under the noses of city authorities.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

The work unfolds as ten fishermen, one after the other, wordlessly and carefully and each in his own way, move their boats to magnificent river locations. Each prepares his tools—a net, a single line of nylon with a hook, or a harpoon—that he casts into the water. The fisherman waits calmly, and then reels in his catch. In unrehearsed actions performed for the first time and recorded in just one take, each gently holds in his arms the large fish he has just caught, and enacts a tender ritual of embracing it, the same way one might embrace a lover. The work is as rich sonically as it is visually.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Photo: Courtesy the artist

De Andrade’s work is in dialogue with the 1959 film “O Mestre de Apipucos” by Joaquim Pedro de Andrade. The artist noted about his work, “it juxtaposes a film about a presumed housekeeper in the house of Gilberto Freyre [Brazilian sociologist, 1900-87], with a historical film about Freyre himself. We can see the complexity of this character that initiated a dialog and constructed ideologies of classes and race, but that himself carried aristocratic attributes—and he is portrayed like that. There are all these dynamics happening with his image and his identity in the film. It is very interesting, for example, to see that he had workers; that there is an element of servitude there. And there is also a temporal element because… I think that, during that time…[Freyre’s] introducing the house servants by name, perhaps signaling proximity, was maybe even an avant-garde gesture. Today, this would not be okay.”

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

The video is set in a village in the state of Piauí, where roughly ten percent of the indigenous population is deaf. Documenting the local community’s unique forms of communication and ritual, de Andrade respectfully recorded their movements and gestures, with particular focus on expressions of belonging, exchanges about social life in the arid hinterlands, the challenges of raising and caring for children, their experiences of frequent harassment, and their memories of lost loved ones.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

In Voyeristico, a dynamic sequence of different individuals’ hands that open wallets is shown in close-up so that only the contents are visible. De Andrade edited short clips together so that the movement fluidly transitions from one hand’s movement to another, until the first hand seen in the film reappears. The sound is based on the rough ripping apart of Velcro fasteners and the rustling of bills, overlapped with breathing sounds—actions representative of desire and the individual’s relationship to money and currency.