Today, I’m calling Didem Pekün, a Turkish–British artist, born 1978 and now based in Berlin. Didem’s lyrical video installations interrogate different ideas of identity, displacement and statelessness.

Didem, thanks for joining me.

Didem Pekün: Barbara, thanks so much for having me. Such a pleasure. Thank you.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: To begin, let’s start by talking about your upbringing and your early education. In the past, you’ve spoken about your interest in music, which began in your teens when you worked as a DJ in Istanbul’s underground music and dance club scene. Could you tell me a little bit about this?

DP: So we’ll go early, very early. We can say that my earliest “music practice” is actually collecting. I remember going with my family on trips and holidays outside of Turkey, to Europe or wherever, and returning home with thirty CDs. It was a perfect opportunity for me to discover new music, to return home with lots of new sounds. I ended up with a lot of CDs. We’re talking thousands.

This collecting lent itself to DJing, basically in Istanbul. I can say I had a rather intensive nightlife in my late teens and early twenties. It was a natural outcome of that phase, that I wanted to have a hand in the music that we were listening to. Some of my friends opened this club, Dixie, which was very close to my house. I would go there and play three, four nights a week. Then I moved to London. So that was a somewhat short-lived period of DJing, but it was a very nice and fruitful period, let’s say. When I moved to London, I think I was about twenty, I started to work at Tower Records. You remember Tower Records? It was a continuation of my music passion, let’s say. Then I started to do a BA in music.

That was the most natural outcome. I spent three years studying music on top of it all.

BL: You did a BA in Ethnomusicology at the School of Oriental and African studies; then you completed an MA at Goldsmiths, followed by a PhD in Documentary Film and Visual Culture. I’m curious, how did your trajectory of these studies stimulate your interest in identity displacement and statelessness?

DP: When I first moved to London, that was pre-education, pre- higher education. I was twenty-five when I started my BA. Finishing high school, I had refused to go into higher education. I wanted to live, as it were. That living involved being displaced, meaning the firsthand experience of being a Turk in the UK, which somewhat shapes your thinking. You can’t be a Turk and not be aware that you’re the Turk in the European countries. It is somewhat a continuous performance of the self, as it were. You suddenly are in a different country. You speak a different language and you sound very different, and there’s all of this “difference” that is constantly in your day-to-day life. I think that initial experience that preceded my higher education, really formed my awareness of being displaced.

When I did the BA, MA, and PhD, and all of them had this undertone. All of my research had the undertone of figuring out what to do with difference… There’s a saying, which I identified with a lot actually, by an American scholar, Alisa Lebow, who became one of my PhD examiners. She wrote in her book about being never fully an outsider and never fully an insider. I think all of my work has this undertone of, you’re never fully an insider because you’ve left “home,” and you never fully are an insider of the new place you went to. First of all, I‘ve never stayed in one place too long. That’s partially because of this constant movement. But there’s also the sense of refusing that kind of fitting in. These experiences, I think, became a core research project that’s ingrained in my genetics, as it were. Life experience defines what we can call an artistic fingerprint: something that’s ingrained in you that just keeps on coming up.

Araf – Trailer 1 from DP on Vimeo.

BL: Doing the PhD in documentary film and visual culture, was there anyone in particular who had an impact on you? We’ve talked about how John Akomfrah’s work was very important for you, but you never studied with him.

DP: I think John Akomfrah is such an eloquent filmmaker. From the Handsworth Songs to The Stuart Hall Project to pretty much all of his diverse work, actually. I guess what I really like about John Akomfrah’s work is his thoroughness. Everything is told through the smallest detail and nothing is rushed. I think I consider myself first and foremost a filmmaker, and I work within the medium. I have a friend, the colleague, Jan Verwoert, who’s a curator and an art critic. Together we’ve discussed this idea and notion of working within the form or working more outside the form, more conceptually. I love the formal aspects of the film, work fully with the medium.

As I like video; I like the possibilities. I like being able to stretch it—the sound, the vision, and what have you. To that end, I think John Akomfrah is a filmmaker who’s worked within the form and who knows his medium and who works with it in very diverse ways. For example, The Stuart Hall Project, which in many ways is very important to me because, not only filmically, but because he did two versions of it. There’s the single channel one. Then there is the three-screen version, which is called The Unfinished Conversation. It’s looped, and it’s slow. Slowness is an important factor for me, as well, taking time to think about things.

BL: Let’s move on to some of your multimedia works, starting with your elegiac two-channel installation Of Dice and Men of 2016, which was presented in a special exhibition, “We Interrupt Regular Broadcasting to Bring You This Special Program!”, that I co-organized at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens in 2018. The installation is very dramatic. It features a towering pair of screens that stand side by side, like a gigantic open book.

You use video as a means to connect so-called everyday events with momentous political events.

There are thirty-five short diary-like entries, mini episodes in black-and-white. With lengths ranging from one to four minutes, each flowed across the tall screens. Each entry received its own formal treatment, turning the episodes into distinct poetic entities.

Of Dice and Men excerpt from DP on Vimeo.

“Did you know that eagles mate for life? And when they mate, they go to the highest points of the sky. They fold wings and plummet towards the earth to separate, only at the very last moment.”

BL: Let’s begin with how the installation opens with footage you recorded as you joined the Occupy movement in London in November, 2011. The work continues on to Turkey, where in 2013 you recorded your own, very hectic movement as part of an enraged crowd that was protesting the murder, several years before, of Hrant Dink, a Turkish-Armenian intellectual and human rights journalist. Tell me more about some of the individual episodes and the larger themes you had in mind for Of Dice and Men.

DP: I think what makes Of Dice and Men very special is that I had no idea what I was getting into when I started that video. It’s kind of ironic because it’s the most ambitious work I did to date, because it took five years. It was five years of continuous recording day-to- day life. In that sense, it’s five year long diary-making. The way I started it was, I read a text that had to do with dice from Alain Badiou, dice throwing and about the repetition, and about it never being the same. Also, this throw of dice is an event. So, there is an event that happens. Then the question is, how do we respond to that event? It’s like this constant day-to-day life. You go out, there’s an event; how do you, as a subject, respond? So, it has to do with our agency, because at that time I was very concerned with the question of agency.

There were a lot of things shifting. There were political subjectivities being awakened: there was the Occupy movement that began in London in 2011, there was the resistance that began in Istanbul’s Taksim Gezi Park in 2013. The days were hopeful. That was the hunch that led me to pick up the camera in 2011. I said to myself, ‘Okay, now I’m going to start a diary.’ Little did I know it would take me five years of recording. Perhaps a bit like Agnès Varda and her 2000 documentary film, Gleaners and I, how she used her camera as if she were gleaning. She goes out, collects bits and pieces, comes home, puts them into her computer and makes things out of the material she collected. That was the kind of methodology that I used. With regards to specific entries, I started with the woman at the Occupy march in London in 2011. She shouts, ‘What we want? We want a revolution.’

That’s the beginning of that time. It is what I, we, wished. Hrant Dink is an ongoing wound in the society in Turkey. It’s a murder that happened in broad daylight. It’s a racial hatred. I think you know very well what it means to have racial hatred that really scars a society, especially someone like Hrant Dink, who just spoke of peace. He had integrity; he spoke of the conscience that called for some form of reconciliation or acknowledgement between Turkey and Armenia. Every year, there’s a memorial on the date of his murder, January 19.

That initial entry basically asks, what do we want? At that time in 2011, I went into a shop in London and I asked, “Did you watch the news? What happened with the march?” Because the tradition is there’s a march, but there’s a police attack. That’s part of the dialectics, as it were. She responded to me, ‘Yeah, but what’s the point? Like what’s the point of walking?’ I wanted to go against this jaded attitude. There is still something to be done.

Something must be done, because I think the entire fight for me is this fight between sides, ‘What’s the point?’ and then the militant, and the discussion between the two. I think the whole video boils down to that.

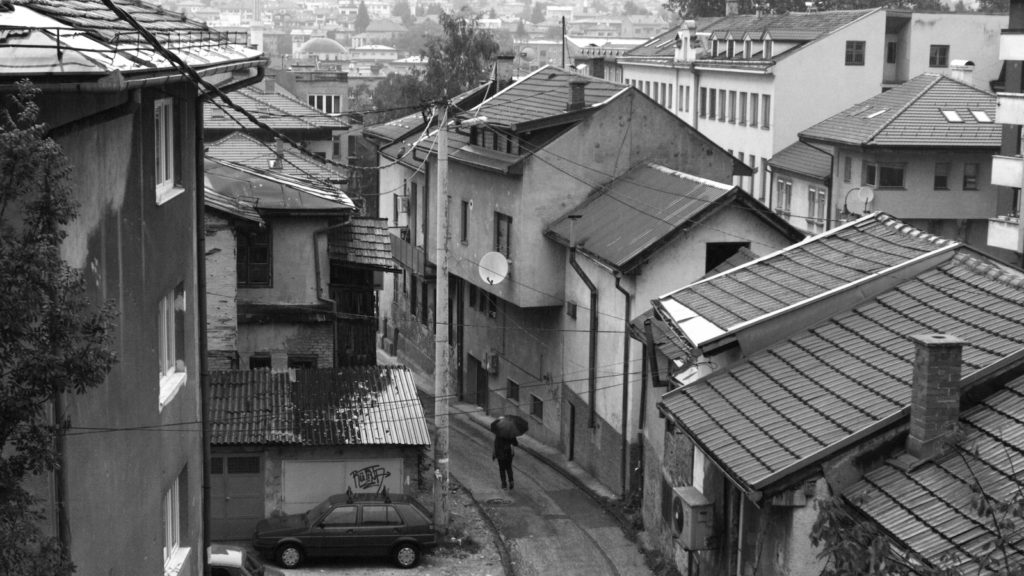

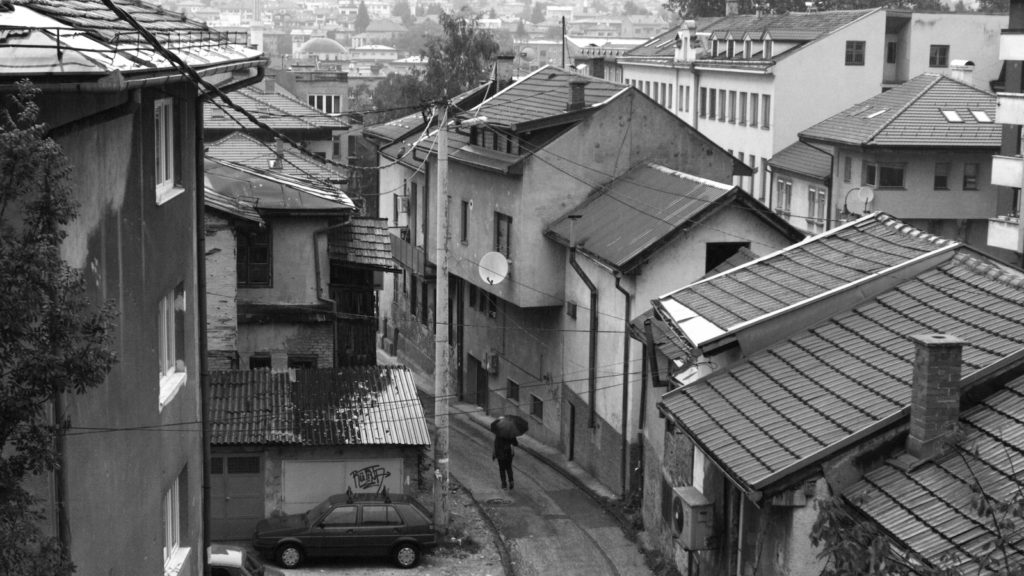

BL: You now live mainly in Berlin, but you remain very invested in what’s happening further east. This was clear when I saw your single channel installation Araf (2018).

To me, Araf is a kind of road movie derived from the purported diary of Nayia, a woman who travels between Srebrenica and Sarajevo. She returns from exile for the 22nd anniversary of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide.

We’ve talked often about the scene of the man who stands high up on the bridge in the old city of Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina. And in very slow motion, he gracefully dives. I’ve heard you reference the story of Icarus as an inspiration. What story were you trying to tell with Araf?

Image: Courtesy the artist.

DP: Multiple stories were at stake there. I have family who came from Mostar, so this migrant story actually took place before me. That’s my connection to the region. I have family that came from Mostar and moved to Turkey. Nayia’s fictional story is actually a semi-fictional story. Nayia is a little bit me, kind of. I created a Nayia through which to say things a bit more freely. There’s this diving tradition in Mostar, which goes as far back as four hundred and fifty years. Dino Bajric is the name of the diver that I filmed. Every year, the winner of the diving competition is awarded the title Icarus. If you jump in the most spectacular way, and there are certain ways and means to measure the jump, you are the Icarus of the year. The Greek myth of Icarus and Daedalus is actually part of their discourse and the tradition, as well.

What I basically did, in a rather far-stretched, ambitious, metaphorical narrative, was think about the tradition of Icarus in a different way. The myth goes that Icarus was too ambitious. He flies too high, and then as he goes too close to the sun his wings melt and he crashes. His myth is actually the tradition of over- ambition and total collapse.

Image: Courtesy the artist.

What I try to do is present the cyclical nature of history, because the history of war in the region, is it just the repetition of one side killing the other side. You know, this war is an ambition. I drew upon Icarus in order to say that. Can we write this history otherwise? How will the cyclical nature of catastrophe after catastrophe ever end? It seems like we just keep on acting out the same script. But actually, it’s somewhat a continuation of Of Dice and Men, as it were, because we’re forever handed the same rolls of the dice. There’s the same shit happening. How will this ever stop? In a nutshell, that’s what I thought about in Araf. I tried to make Icarus fly. He won’t be the traditional person who flies too high, gets too ambitious and dies. I tried to present it as, perhaps we can think of a future that is otherwise.

Image: Courtesy the artist.

BL: I saw Araf in Athens in a beautifully installed way. The installation was in a dark, black box kind of dark gallery, where there was a large, luminous projection and sound system with good speakers. I was totally immersed in the work. I think your skillful handling of sound comes out of your DJ experience. You are a wonderful editor. Do you agree?

Image: Courtesy the artist.

DP: I mean, I agree to the extent that I spent so much time with sound, an incredible amount of time editing. I would refrain from calling myself ‘wonderful,’ but would say that sound is the part of the film I spend so much time in. And then with the sound, I have collaborated with the same people on the last three films, Fatih Ragbet and Eli Haligua. They are sound designers, and are extraordinary. Basically, once I have the film, we start thinking about the audio together. With Araf they came up with a wonderful sound design in 5.1 surround. Sound is very central, and as you say it’s an immersive, experiential sound design. I’m a bit pedantic when it comes to editing and sound.

BL: In all the work of yours I’ve seen, there seems to be an optimism that positive change will be brought on by new technologies. Is that something you believe or is that something I’ve intuited?

Image: Courtesy the artist.

DP: I am not sure at this point. I don’t feel too hopeful. I think we are sitting on a threshold, and there’s a lot of work that falls on all of our shoulders to make this change, the shift into something that will at last destroy some systemic racism, at last destroy some form of systemic sexism or whatever. Technology to me is secondary. I saw technology as providing a lot of help to us in the Gezi Uprising, for instance. Technology helps us see what’s happening around the world and connect to each other. But I still think technology is secondary.

There’s a lot of work on our shoulders to be done using that technology. I guess a lot of the optimism revolves around this constant fight. It’s nihil and the militant inside of me that are constantly fighting. But I use the technology a lot to do things within the activist world. The kind of collaborative work I do with my friends, we use technology for that, for sure. We benefit from it. Sometimes one of us gets very tired, and then the other person continues. That’s another application of it. But I think the two are not separate from each other, which is what I’m trying to say. The human needs to constantly work, work on herself, to remain determined, to see the change, determined to do the work that needs to be done to see brighter, better, justice and equality.

BL: We’ve talked a little bit about how you’ve described yourself as someone who ceaselessly changes language, changes SIM cards, changes humor, changes cities. You seem to live a life forever split between two cities. Do you feel fractured as a person and as an artist? What keeps you whole?

DP: This is such a wonderful and core question. I feel forever fractured. Living in London and Istanbul, there was the fracture of two cities. Then the cities multiplied. Now, there are more fractures. There’s obviously my home, which is Istanbul, and where I reside now, which is in Berlin. There’s the perpetual effort to reach and keep my people close to me. It takes a lot of effort to keep that communication running, and is what keeps me whole. I have to add that I have a Buddhist practice. That keeps it together, keeps me centered as much as possible. But I can’t claim to be an extremely centered person, but that’s from where I try to draw my wholeness. To that end, I think Araf was very much a film with that tone. Despite everything, there is a centeredness, and a connection. There’s imminence and impermanence. All of these things are rooted in my Buddhist practice.

BL: I’d like you to tell me about someone who’s been very important in your life, and that is the businessman and philanthropist Osman Kavala. Maybe you could tell me a little about how he’s been such an important figure in your life.

DP: Thank you so much for making time for Osman Kavala. Osman Kavala is a unique person, a role model, such a figure of generosity, decency, and I can even say of optimism. I met him in 2008. I had just returned to Istanbul from London, and a mutual friend told me, ‘You should meet Osman Kavala. I think he will understand what you want to do.’ Out of the blue I sent him an email. I said, ‘Hi, I’m Didem, I did this and this. I’m making a film, and I’d like to meet you.’ He replied, ‘Sure, would you like to come in two days at this time, would it suit you?’ Such is Osman Kavala. He is so kind and so generous. There are so many people I am in touch with, and they give you an appointment in three months and they put you in touch with their three assistants. Osman Kavala will tell you, “I can do in two days. Would it work for you?” He’s so kind and generous like that.

Image: courtesy Didem Pekün

That’s how I met him. He then supported three films, and was there for my PhD. What Osman Kavala does is, he is there for the arts because he thinks the arts create this platform of communication, of dialogue, a place to think about these burning questions, that other platforms might just make it a bit too stiff. He really believes in artists. He doesn’t even care if he likes the film I make or not. He wants to enable artists to continue making their artwork. Then through this cultural work, we can have dialogue with each other. I would say that he is a facilitator of dialogue.

Osman has been in prison for almost 1000 days, as of now on July 27. The European Court of Justice acquitted him. He should have been freed, but he’s not. He’s a political prisoner. I can tell you that all of us are so frustrated. We went in and watched the show trials, where he never expressed words with distaste.

Who is Osman Kavala? from DP on Vimeo.

He has never expressed bitterness, in any of the letters that I’ve exchanged with him. We’ve talked about work. With me he still exchanges ideas about the new film I’m making, about the script. And I know from Asena Gunal who runs Anadolu Kultur, his company in his absence now for three years, I know from Asena that he’s in good spirits. I mean, in the midst of all of this, as we’re spending so much time trying to keep centered and getting angry, we are still taking inspiration from Osman, who has been in prison for three years. Osman Kavala is such a person.

BL: Thank you for sharing. You’ve mentioned how important your academic teaching career is. What are you most surprised by in your new students?

DP: I love it when they’re surprised. I love it when they discover something about themselves or about the medium of video. To me, that’s what the whole work of teaching is about, to share a new language, because video won’t be a hit with everyone. You might be an art student, but you may hate video. It’s very detailed work. But when students discover video as a new language, then suddenly they shift and make it their own. That for me is the most fulfilling. I’ve had various students from five or seven years ago call me during CORONA and ask, “What do we do now?”

I had no answer, because I was figuring it out for myself as I spoke. Their calling to ask me what they should do, shook me out of my inertia. I had to think, how do we get back to filmmaking in this time? I guess teaching is a two-way thing.

BL: I agree with you. So, what is next?

DP: Right before CORONA hit, I was very close to shooting a new film. It was going to be a very crowded film, crowded in the sense that we had about fifteen actors. There would be big sets, unlike my previous, much smaller-teamed works. That is still pending.

Image: Courtesy the artist

I’m still trying to shoot it. It is called Disturbed Earth. I collaborated with two script writers and together we wrote a script based on archives about the UN and NATO’s non-action during the Bosnian war. The whole film takes place in these bureaucratic meeting rooms. The audience knows that something horrible is happening, but we just watch these bureaucrats dancing around decision- making. It’s that choreography of bureaucratic incompetence. I’ve been invested in the film for almost two and a half years now. After that, I intend to make something on a much different topic.

BL: I’ll be sending positive energy.

DP: Please do. You’re like good angel Barbara. Whenever you’re around, something good happens.

BL: That’s lovely to hear. Now, here’s my very last question, which I’m asking everyone in the series. Do you consider yourself a media artist?

DP: I think I’m actually a very straightforward filmmaker, even though I’m not fully in one area or another. I can say I’m a video artist, but then I go and make a film which enters festivals, and so on and so forth. Then I get tired of that, and make work that goes to galleries and museums. I’m interested in sitting on a fault line there as well, where I’m neither a straight-forward filmmaker, nor only a video artist. I use both of these mediums to be able to make a film—a filmmaker at the core.

—

Support for “Barbara London Calling” is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and Independent Curators International in conjunction with their upcoming exhibition, “Seeing Sound,” curated by Barbara London.

Be sure to like and subscribe to “Barbara London Calling” so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out BarbaraLondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

“Barbara London Calling” is produced by Bower Blue , with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded June 16, 2020; it has been edited for length and clarity. All photos courtesy of the artist.

Images & Video

Born in 1978 in Istanbul, Didem Pekün is an artist who divides her time between Istanbul, London and Berlin. A love of jazz and soul music inspired her to explore the Yoruba language and the culture of Nigeria, while studying ethnomusicology at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. At Goldsmiths College, she completed an MA and a practice-based PhD in documentary film and visual culture. Her research-based media art practice she addresses how violence and displacement destroy and define life. She is currently a fellow at the Graduiertenschule, UdK Berlin.

A pair of towering screens stand side by side like a gigantic open book, portraying images of everyday events coupled with political ones. Pekün uses video as a means of digging into the emotional cache of memory, specifically events in her own home cities of London and Istanbul, ones that dominated international news between 2011 to 2014. Short diary entries, mini-episodes, flow across the tall screens. Weaving across the screens, each episode has a sense of authenticity in its portrayal of events, unlike the blur of mediated news that networks consistently spew out.

Indeed, Pekün originally picked up her camera hoping to capture and make sense of a present that she felt was shifting around her—palpable in both the events unfolding in these cities, but also in the emergence of a new political subjectivity that was awakening from its slumber. Dice are a leitmotif of the installation, an allusion to how life often appears as a game involving chance.

Image: Courtesy the artist.

Image: Courtesy the artist.

Image: Courtesy the artist.

Image: Courtesy the artist.

Image: Courtesy the artist.

A kind of road movie, Araf is drawn from the purported diary of Nayia, a woman who travels between Srebrenica and Sarajevo, to Mostar in Bosnia, as she returns from exile for the twenty-second anniversary of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide. The film is guided by Nayia’s notes of the journey, which merge with the ancient Greek myth of Daedalus and his son Icarus. The myth, symbolic of man’s over-ambition and inevitable failure, is woven throughout the film as a way to think about exorcizing the vicious cycle of destructive events happening in the future and of a possible reconciliation. Nayia considers Icarus from a different perspective. She sees optimism in the act of taking a leap, and the braveness of diving into the unknown, in particular during an era of radical instability. Araf traces these paradoxes through Nayia’s displacement and her return to her post-war home country. The discord between displacement and permanence never seems to cease.

Pekün once noted:

I was in a trance when I was making this film, or perhaps in a nightmare I was unable to snap out of. Everything fell into place in that manner, in the sense of how the team came together, how the production materialized out of a series of what almost looked like impossibilities…The film is also an elegy in slow motion; an elegy of an event that the world fast-forwarded. I wanted to rewind and replay and really look to see through the commemoration, because commemoration is an act of protest against this repulsive phenomenon of genocide and the desire to erase a people from history.

Image: Courtesy the artist

In a dimly lit conference room, six men gather around a circular table with papers everywhere, a never-ending meeting in a safe area at a safe distance. The men deliberate, sending messages and directions to officials off screen. No decisions are ever made, as the tragedy unfolds elsewhere.

Disturbed Earth was filmed as a one-day rehearsal, with a script based on the archived conversations at the UN. The theater of war occurring off screen is mirrored in the film’s set, where the actors embody a language at odds with the reality outside. The film is a critique of bureaucracy and its inability to act at a time of crisis.

.

Who is Osman Kavala? from DP on Vimeo.

Who Is Osman Kavala? Animation film by Osman Kavala’s artist friends. 2020. 1:54 min.

On the 950th day of Osman Kavala’s illicit detention, ten artists uploaded and shared their animation. The artists are Tan Cemal Genç, Murat Çelikkol, Didem Pekün, Asena Günal, Çiğdem Mater, Arsinee Khanjian, Özge Ersoy, Merve Ertufan, Evrim Kavcar, and Ayça Telgeren.

Image: courtesy Didem Pekün

Osman Kavala (born 1957) is a Turkish businessman, who founded several publishing companies in the 1980s. He went on to become a philanthropist of the arts, and a supporter of civil society organizations in Turkey. Kavala is the founder of Anadolu Kültür, a nonprofit arts and culture organization based in Istanbul. In 2019, he received the European Archaeological Heritage Prize by the European Association of Archaeologists for his efforts to protect and preserve important examples of cultural heritage in Turkey. The same year, he received the Ayşenur Zarakolu

Freedom of Thought and Expression Award by Human Rights Association, Istanbul. Since 2017, Kavala has been arrested and acquitted by the Turkish government, although currently, he is still incarcerated as a political prisoner.