Barbara London: My guest today is the Mexican artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer. Born 1967 in Mexico City, Rafael emigrated to Canada, where he is now based. His work has been shown across the world, including at the 2007 Venice Biennale, where he was the first artist to represent Mexico. Rafael’s interactive digital work examines social and political issues using technologies that include surveillance cameras, artificial intelligence, projection mapping and robotics. His survey exhibition “Obra Sonora” is on view at the Baker Museum in Naples, Florida, through June 15th, 2025. Rafael, thank you for joining me.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: It’s my pleasure, Barbara.

Barbara London: I’m delighted to be talking together today. You are one of the most energetic and affable artists I know. You were born in Mexico City, then found your way to Vancouver, where I believe you were active with radio. Is this when you first started to think about technology and communication?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Definitely, yes. At the University of Victoria of British Columbia, I met writers, actors and composers. And even though at the time I was studying chemistry, I would often go to the radio station CFUV, where my friends had a performance and radio program mostly based on music. When I moved to Montreal, I started a radio program called PoMo CoMo, the Postmodern Commotion, at CKUT Radio McGill.

That started my way into performance, because it was an experimental approach to radio. We would do a lot of sound art and interviews. But in essence, the spirit of radio needing airtime to be filled is how I got started in culture.

Barbara London: I know you come from a family where there was a lot of music going on.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: That’s right. I am the son of nightclub owners in Mexico City, so partying has been a big part of my life history. And to this date, I think that good artwork is a good party. You can set up the music, you can set up the ambiance, but it’s only when the public shows up that the party really starts. So, I pay very close attention to what the role of the public will be.

Surface Tension

1992

Shown here: Trackers, La Gaïté Lyrique, Paris, France, 2011

Photo by: Maxime Dufour

Surface Tension

1992

Shown here: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Pseudomatismos, MUAC Museum, Mexico City, Mexico, 2015

Photo by: Oliver Santana

Barbara London: Let’s now dive right into your first interactive work, Surface Tension from 1992. It’s a curious work. It features an image of a giant human eye that follows the observer with Orwellian precision. Could you tell me why the title, Surface Tension?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: This was in 1992, and at the time I had experienced some early VR experiments. In media art in the early 1990s there was this divide between the screen’s virtual world and your body—you could not reach out to it. I like the term from chemistry, surface tension, which describes how forces react at the boundary between two media, for example, a liquid and a gas. I felt surface tension was always present at the interface between virtual and real.

What I wanted to achieve was for the virtual world to look back into the space of our own bodies. I was inspired by traditions of painting where the protagonists are involving the public. I’m thinking of Diego Velázquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas, and also of Leon Golub, or any number of different artists who have addressed the line of sight, and worked on the question of who is the observer and who is the observed.

I did that, but this time with a massive human eye that was quite sinister, the feeling of the eye following you. And to this date, I think that the piece is valuable because it makes tangible the way that these data mechanisms are tracking us—it’s making that evident and very embodied.

Barbara London: I don’t know if it was a little birdie or something I read. Does Surface Tension have something to do with the French philosopher, Georges Bataille’s text, The Solar Anus written in 1927?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Yes, absolutely. I was reading Solar Anus in 1991 at the time of the first Gulf War and thinking about Bataille’s “violating ray of light”. As you may remember, in 1991 we first learned about these so-called intelligent bombs, which had the capacity to have executive override to locate their target autonomously. This was described by Manuel de Landa in his terrifying book, War at the Age of Intelligent Machines (1991). So, there was this tension I thought was productive, making sure this eyeball was representative of that predatory violence, but also of that agency and autonomy the computer system could be endowed with.

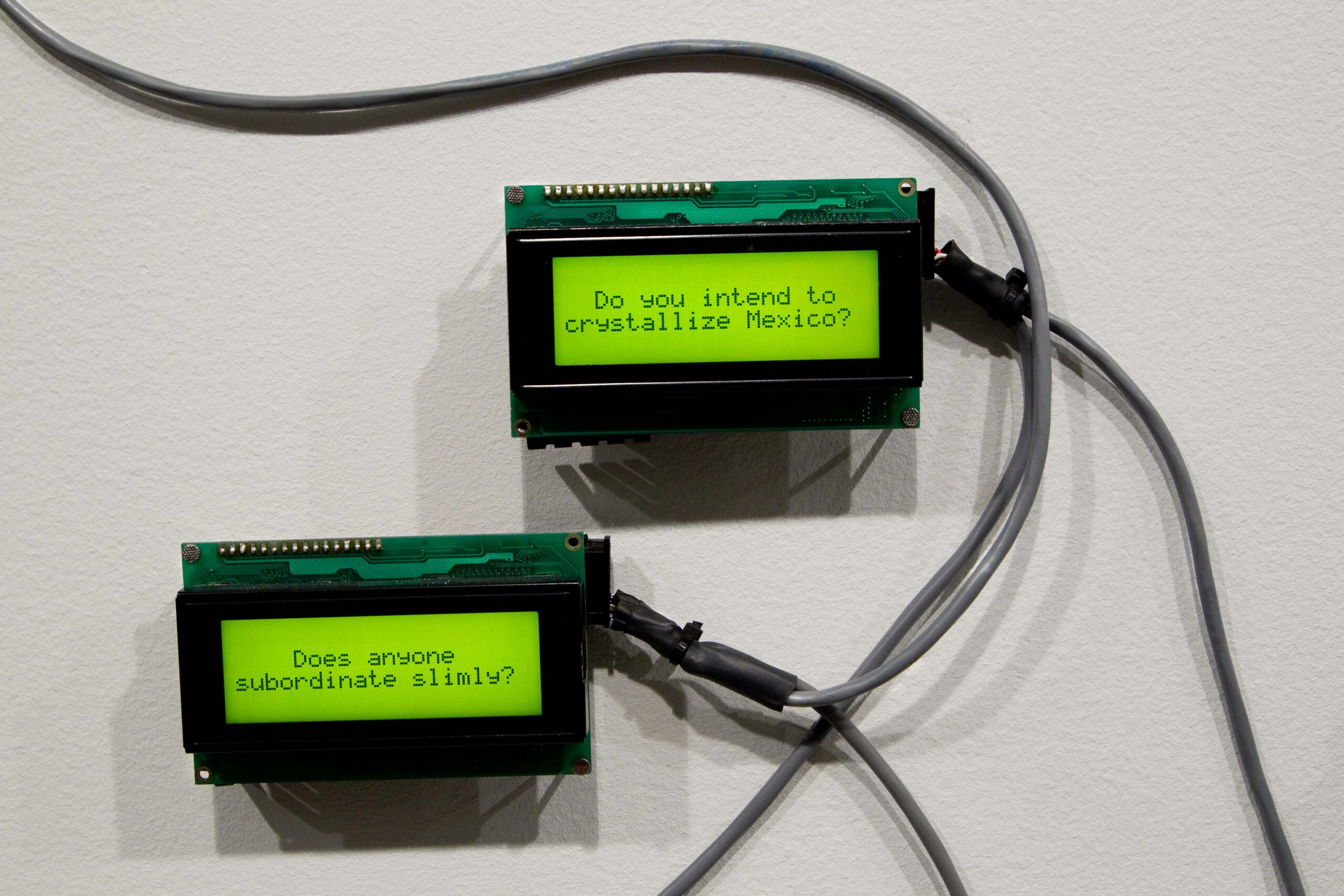

33 Questions per Minute, Relational Architecture 5

2000

Shown here: Recorders, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia, 2011

Photo by: Antimodular Studio

33 Questions per Minute, Relational Architecture 5

2000

Shown here: Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, United Kingdom, 2010

Photo by: Peter Mallet

Barbara London: Now, let’s move on to your work from 2000 and that is 33 Questions per Minute (2000) in MoMA’s collection. There are twenty-one tiny LCD screens installed on a wall with elegantly dangling wires that connect each tiny screen to a computer. On the adjacent computer keyboard that sits discreetly on a pedestal, viewers are invited to type in a question. The work’s computer program uses grammatical rules to combine the just typed in words and then, is able to generate unique fortuitous questions, let’s say about 4.7 trillion of them.

The automated questions posed by the viewer are presented on the screens at a rate of 33 questions per minute, which is the threshold of readability. I believe this piece is loosely based on the long tradition of automatic poetry. It’s full of anti-content. Could you tell me what is going on with this work?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Yes, absolutely. This piece was a collaboration with linguists in four different languages, and the rules are straightforward: The first rule is, choose words at random from a dictionary. The second rule is, ensure that you can compose a grammatically correct question,—so the system knows how to conjugate verbs, and add adverbs, nouns etc. Then, the third rule is, never repeat the same question. The result is a stream of constantly updating series of unique questions, that are often quite ridiculous. It asks things like, “Will you bleed in an orderly fashion?”, and it just keeps asking them at a speed that is the threshold of legibility. It’s frustrating, because you can’t keep up with a barrage of questions that it comes up with.

Originally, I premiered it in 2000 at the Havana Biennial in Cuba, in the Wilfredo Lam Art Center. I had heard that the internet was illegal for Cubans to use, but was available to foreigners like me. So, I got internet access and connected my system of automated questions to it, then asked people to add their own content into the automatic flow.

The spirit was if someone were to write something politically sensitive or otherwise could be censored, the authorities would not be able to determine whether the question was asked by a human or by the computer, creating a kind of Trojan horse that would allow people to express themselves freely. Interestingly, the piece had a very different outcome I did not anticipate.

I had thought people would express themselves about the political situation, but in fact, they were just adding flirty and sexy content. I like that a lot—that as the author of an artwork you are not necessarily in control of what’s going to happen with it, and the outcomes are surprising.

Since 33 Questions per Minute entered MoMA’s collection, and a few other museums have shown it, I think of it now as a very early version of an AI agent. The piece is, in a way, the opposite of the Turing engine: our incapability to know if the question was written by a human or a machine is in fact the way to curtail the systems of control.

Barbara London: I want to go on with one fact about the piece. In advance of the MoMA acquisition, you sent me a 30-page operating manual, which MoMA’s media conservator and I carefully read. You answered a few of our technical questions. A document like this is how you prepare your work for its future, right?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Absolutely. And in fact, what you guys did at MoMA with this work was so important because at the time, this was 2004 or 2005, there was a genuine and understandable concern over the conservation of digital media. What would happen if, for example, the computer we used for 33 Questions per Minute died? It was a Windows 95 machine programmed in Pascal, which very few people know how to program anymore!

So, I gave you the source code, I gave you the schematics, I gave you all of the elements that make up the artwork. Your conservation department together with a graduate student, managed to port the entire project from a Windows 95 operating system to a Linux operating system, and from Pascal to C++. This meant it was not necessary for the Museum of Modern Art to stockpile Windows 95 computers in order to play back this project forty years into the future, but rather, the code as the instructions that make up the artwork, can be re-performed with languages or devices of the future.

I started a “best practices” for conservation of media art based on that project. I felt we needed to connect ourselves with the traditions of instruction-based art. The typical example is the work of Sol LeWitt, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Tino Sehgal, or even Moholy-Nagy when he made his painting over the phone in the 1920s. Citing these precedents helped the museum community relax about media art, because if you have this code and these instructions, you can now interpret it almost as if it were a musical score. This helped me greatly. The moment MoMA acquired that work, other museums and collectors then understood it is not an impossible mission to conserve a work of digital art.

Barbara London: Shortly after MoMA acquired 33 Questions a Minute, I included it in an exhibition entitled “Automatic Update”, in 2007. I organized the show when the dot-com era infused media art with a heavy energy. How did this moment affect you in other ways, and your work?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: That show made many media artists feel we were getting legitimated. To a degree, all of the work I had done prior to the MoMA show had been in festivals and institutions dedicated to Media Art, like Arts Electronica, V2, Transmediale, ZKM, and at Tokyo’s ICC. And though I love them very much, I think the important step of normalizing this art type as something that can coexist with established fine arts required museums like MoMA, as well as writers and curators such as yourself, to consider them in other traditions of experimentation.

Of course, now we know, there were decades of work already existing in the domain of interactivity, performance, cybernetics, computer-assisted drawing and so on. Only it was just not common to see it featured in a museum. The idea that MoMA would show and collect this work and care for it was really important. This also happened at the time I was exhibited at the Venice Biennale, which again is another institution that legitimizes contemporary art.

My work was finally entering a platform of dialogue with other media as opposed to pretending to be original or new, or just inside a very specific nerdy niche. Of course it is part of that niche, but hopefully it also has questions for society in general.

Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Relational Architecture 23

2019

Shown here: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Bowie High-School / Parque Chamizal, El Paso / Ciudad Juárez, Texas / Chihuahua, United States / México, 2019

Photo by: Monica Lozano

Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Relational Architecture 23

2019

Shown here: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Bowie High-School / Parque Chamizal, El Paso / Ciudad Juárez, Texas / Chihuahua, United States / México, 2019

Photo by: Monica Lozano

Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Relational Architecture 23

2019

Shown here: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Bowie High-School / Parque Chamizal, El Paso / Ciudad Juárez, Texas / Chihuahua, United States / México

Photo by: Monica Lozano

Barbara London: Radio continues as a medium for you. For example, your work, Border Tuner from 2019 straddles the US-Mexico border. You designed Border Tuner to interconnect the cities of El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juarez in Chihuahua, Mexico. The work consists of powerful searchlights that make bridges of light, that open live sound channels for communication across the US-Mexico border. The piece can be modified by visitors at six interactive stations, three placed in El Paso and three in Juarez. What was on your mind in 2019 with this work?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: This was a time of intense adversarial energy, mostly coming from Trump who had famously said things like, Mexicans are rapists and needed to be shot in the legs and so on. This vitriol had created, for example, the energy for a mass shooter to commit the Walmart massacre of Latinos in El Paso. The tension around that racial divide and that antagonism, the hostility that the United States is undergoing right now again, was the context.

Having been to the region eight times, I had an opportunity to talk to local artists and activists and ask, “what kind of role can art have at a time of this division?” Among the fascinating things they said is, “we don’t want you or any other privileged artist to come here, do a project about the wall, photograph themselves, and then leave without a legacy”, and “we are sick of the wall…what we want is an artwork for listening to each other.” I found that so beautiful. The spirit of Border Tuner, is not to only to create visible bridges of communication between the cities, but also to show that there are already existing bridges between them historically, fraternally, environmentally, economically. These are sister cities where 70% of people on one side have family members on the other.

El Paso del Norte was already a town a hundred years before the United States even existed. The project was meant to present a continuity, a landscape where people could come together and listen to each other, as opposed to be divided. It’s one of my favorite projects, not because of what I did, but because tens of thousands of people came to the border to speak to each other.

What we heard was very moving: from people mourning, or connecting with relatives, to fun serenades, flirting, and singing. Also, some surprising material. For example, we heard a veteran of the Vietnam War who fought for the United States speak about being deported to Mexico. We heard poets, rappers, wrestlers, and indigenous communities.

There was a true diversity in the field. That’s what this kind of artwork can do—present a platform for people to self-represent.

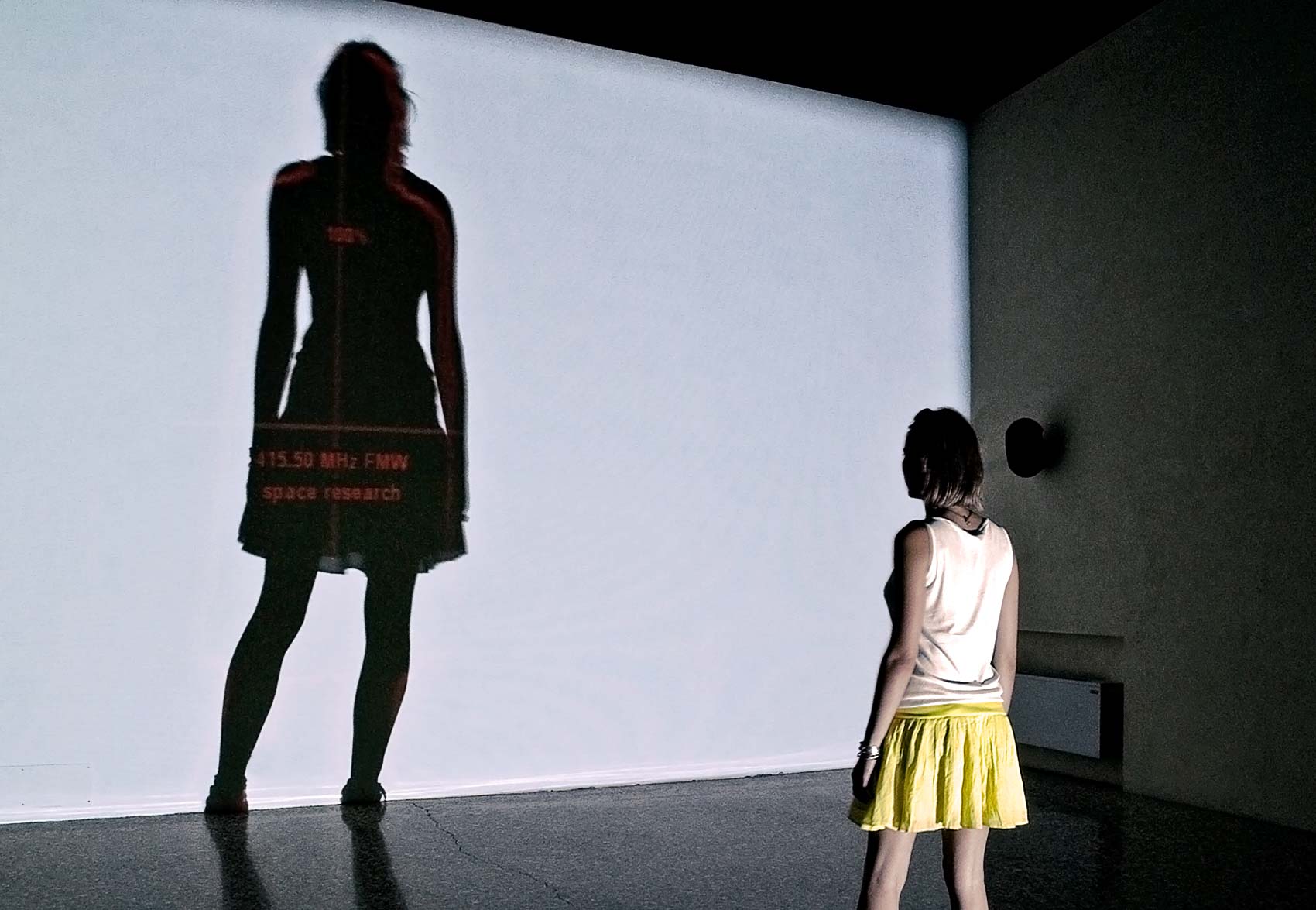

Shadow Tuner

2023

Shown here: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023

Photo by: Lance Gerber

Shadow Tuner

2023

Shown here: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023

Photo by: Pierre Tremblay

Barbara London: Let’s move on to Shadow Tuner from 2023. It’s a shadow play for listening to global radio streams. Radio again. This project was made in very large-scale last year in Abu Dhabi, with a large audience of very excited users. A small cozy version of the piece was recently shown in your recent exhibition, “Caressing the Circle” at bitforms Gallery in Manhattan. I’m curious what’s up with this work? Also, perhaps you could say something about how you are very comfortable having a work be small or big.

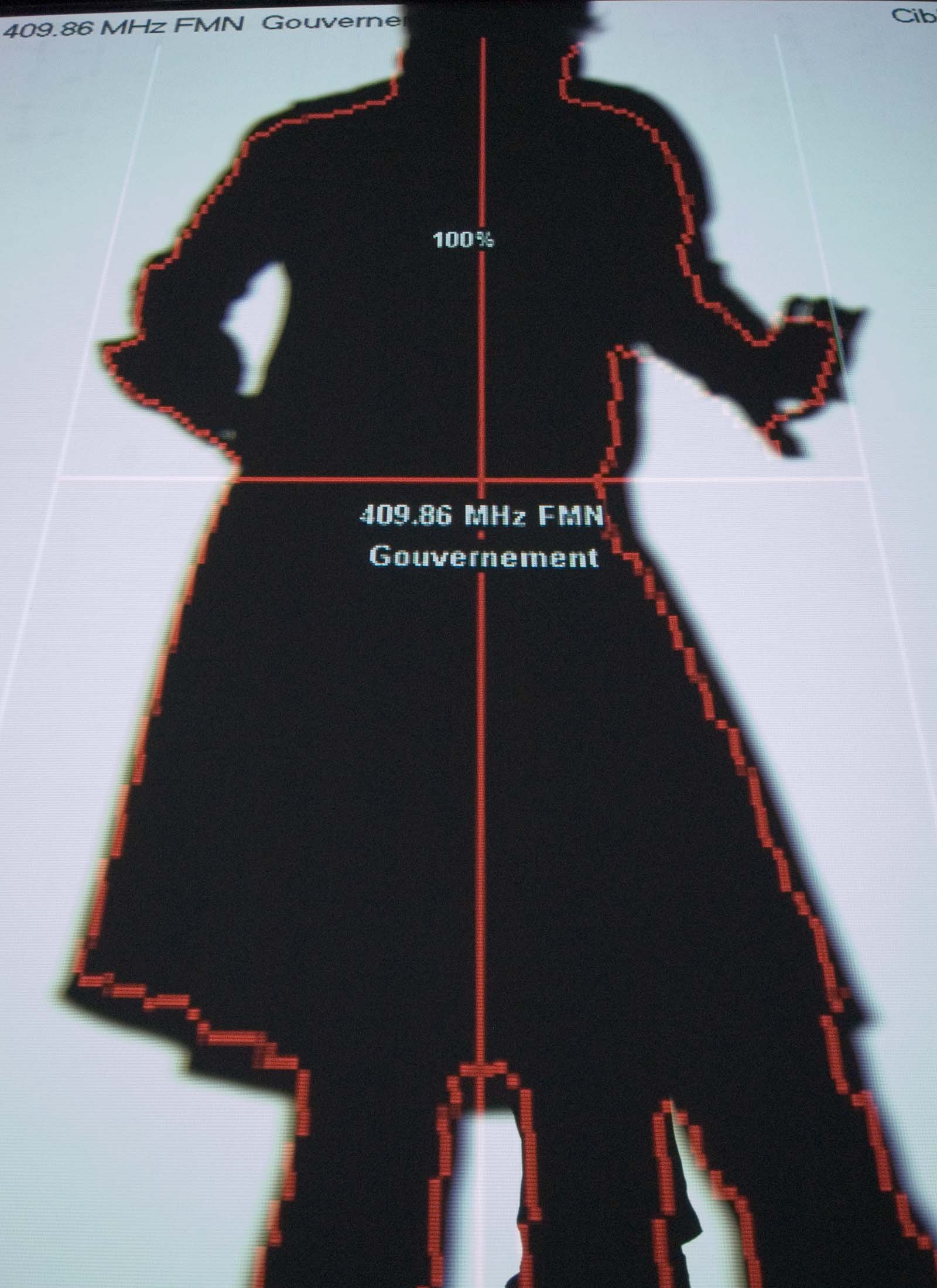

Frequency and Volume, Relational Architecture 9

2003

Shown here: Some Things Happen More Often Than All Of The Time, Mexican Pavilion, 52 Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy, 2007

Photo by: Antimodular Research

Frequency and Volume, Relational Architecture 9

2003

Shown here: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California, United States, 2012

Photo by: Natalia Puzisz

Frequency and Volume, Relational Architecture 9

2003

Shown here: Musée d’Art Contemporain, Elektra Festival, Montréal, Québec, Canada, 2005

Photo by: Antimodular Research

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: In 2003, I made a project called Frequency and Volume, which uses a shadow play for people to tune radio scanners and eavesdrop into any frequency from 150 kilohertz all the way to two gigahertz. The computer would track movements of visitors’ bodies and scan the spectrum with that information. As you moved from left to right you could tune, for example, air traffic control or taxi dispatch sequences, or analog phones. Fast forward to today, those airwaves which were in the electromagnetic spectrum, open and unencrypted, are no longer possible to hear because now everything goes through internet connections.

Shadow Tuner is a contemporary version of Frequency and Volume, but instead of electromagnetic signals it tunes up to 12,000 geolocated internet radio streams from around the world. Unlike Frequency and Volume which was a wall-projection, Shadow Tuner uses a spherical projection of the Earth as an interface. As your shadow covers different cities in the sphere, you hear live what those cities are broadcasting.

As you said, this work originally was presented in Abu Dhabi as part of an exhibition called “Translation Island”, where it was presented as a spherical projection onto a 14-metre diameter balloon. Carl Thoma, a dear collector who has supported my work over the years, saw the work and wondered if we could make a small version of the work for his foundation? And that’s how come we made the small LED sphere that you saw at bitforms gallery.

The capacity for an artwork to change scale, I call vectorial, —a conceptual work can be realized in different scales depending on the setting. Whenever I’m asked by younger people, “Hey, how would you get your start in media art? How can I make large-scale pieces and so on?” I always remind them that the artist proof, the prototype, the original concept, a maquette is a small thing and it can already contain all of the different complexities of interaction and devices you need. Then that can be scaled up, if you have the budget. The spirit is, you tinker around with a smaller version you can produce or maybe reproduce, but also use as a prototype to convince a collector, a festival, or a museum to make a large version of it. Of course, not all pieces can be scaled, but this one in particular was not difficult to do.

Barbara London: Now I have a question for you. I’m curious to know whether you and your team are using the updated term “simulation technologies”. I’ve heard that some people are not using the terms VR and AR because those are too reductive. So, I wonder if that is something that you are doing, simulation technologies?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: We like the word simulation. If it’s overlapped with reality, then that’s an augmentation. Digital continues to be a word that we use a lot. Interstitial is one of my favorites. Intermedia, is a term from dear Dick Higgins and is in Fluxus’s history; it is a word that has a lot of meaning and importance. So, intermedia, I like better than interdisciplinary, and definitely better than multimedia and virtual.

But, we are happy to call it whatever people want to call it. Right now, our pet peeve is the word immersive, which is being overused. And sadly, it is signifying a plethora of experiences which separate the public from the real problems of the earth—showing you virtual butterflies while the real ones are being decimated or showing you artworks that you have already seen ad nauseum. So, the works that we do that have an immersive quality we’re now calling inversive. We prefer this switch because it refers to using technology to refer us back to reality rather than providing a passive spectacle that distracts us. In the old words of the Mexican Zapatistas “we are not asking people to dream, we are asking them to wake up”.

Barbara London: Then there is another term that I think you have a lot of thoughts on, and that is the blockchain. What is the blockchain’s potential for media art and for artists?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Back in 2015, I gave a talk about conservation from an artist’s perspective. I had mentioned the possibility of using blockchain for a certification system that could be referenced globally and independently. This is something I still believe has some power. The problem we have is that with the arrival of NFTs and in general Web3, there is a possessive individualist, let’s call it vampiric and necrophiliac, emphasis on owning things, on property. Marcel Duchamp used to say that an artist is a creator of context. However, the context of NFTs is, unfortunately, financial, it is “a digital wallet” with pyramidal speculation and marketplaces—so much of it is about monetary relationships. I’m just genuinely not interested in that space. Even if I do sell my work to collections and I am part of the art market, I am insisting on a social approach to art.

As a democratic socialist, I believe that education and healthcare should be free, that we should have antitrust legislation to avoid oligarchs. We should have environmental checks. And none of these things are possible with the current crypto bros running blockchain because it’s exactly the opposite of having a central, accountable government that is democratically elected, that has the expertise to address a social and common good. Crypto is libertarian, and things like the commons.

I know there are people who believe that crypto and blockchain-based work could have a usefulness to people who are left-wing like I am, but I have not seen very many examples. I’ve expressed my position to several companies and galleries that want to mint NFTs of my work: “I will definitely produce NFTs so long as we find a way for crypto to never be involved.” If I can have a smart contract that specifically prevents trading in crypto then, I will do an NFT, —but I know it won’t happen.

Having said this, I do have friends who have been ignored by the existing art market who have managed to make some money out of the NFT world, and I think that’s amazing. But I think it’s very disingenuous for artists with privileges such as myself to just go into NFTs because it’s interesting. There’s nothing interesting about them other than the capability to certify somebody invested in it and their investment has been recorded. It’s almost like an accounting facility. As you can see, I’m not the biggest fan, but again, the problem is not blockchain, the problem is crypto. And as an extrapolation of crypto it’s capitalism. Let’s blame capitalism and you will never be wrong.

Barbara London: I have one last question and maybe spins off what you just were talking about. You have said, and I quote, “The artists that interest me most are those that are improvising the most. These are the ones that draw closer to the risk of uncertainty, those who seek things that aren’t computerized.” Do you want to explain?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: I’m not sure that’s exactly what I said. It sounds like a translation. It’s not that the art I’m interested in is outside of computation, it’s that computation can’t really improvise. I love the fact that by definition, an algorithm cannot produce a random number. There is an entire branch of mathematics called pseudo random number generators, which is based on the concept that if you use a program to generate a random number, it follows that you can use the exact same program to generate it again.

This incapability for computers to come up with an uncertain number, this incapability for computers to improvise is something that I see as a tiny little window of hope for humanity. Because among the things that we can do is we can improvise. The other thing that we can do that is much better than AI, and another reason why I’m hopeful is that we die. Dying is something that computers can’t do. And when I say we die, I don’t mean just us physically, but also in terms of forgetting.

There’s an entire section in Nietzsche’s The Genealogy of Morals book 2 about active forgetting. If it were not for the fact that we forget, we would not mutate. And if we did not mutate, we would not evolve. These are my two not anti-AI positions because I don’t have an anti-AI position, but I do note with interest that their incapability to improvise and their incapability to die sets us apart.

Barbara London: Well, that’s great. A great way to close.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: And on that, this podcast dies.

Barbara London: Rafael, thank you for taking the time to be in conversation.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Thank you.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Ryan Leahey, with audio engineer Amar Ibrahim and production assistant Sharifa Moore. Web design by Sol Skelton and Vivian Selbo.

Support for Barbara London Calling 3.0 is generously provided by the Richard Massey Foundation and by an anonymous donor.

Special thanks to Masayoshi Fujita and Erased Tapes Music for graciously providing our music. Thanks to Independent Curators International for their help with the series. Additional thanks to Kerosene Jones and Vuk Vuković.

Be sure to like and subscribe to the podcast so you can keep up to date with new episodes in the series. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

This conversation was recorded October 29, 2024; it has been edited for length and clarity.