Barbara London: My guest today is Kameelah Janan Rasheed. Born 1985 in East Palo Alto, California, she describes her childhood as that of a Muslim kid enrolled at a Catholic school, who attended Mormon school dances, went to Shabbat dinners and attended Sunday Church services with friends. Today, Kameelah is an artist, author, educator, a great lecturer, and a self-described learner. Kameelah was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2021. Currently, she’s teaching full-time at Yale University as an instructor in the sculpture department. She teaches Thesis, Body, Space, Time, and next semester will teach a self-designed course entitled The Word is the Fourth Dimension. Kameelah, thank you for joining me. There is so much to discuss with you.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Thank you for having me.

Barbara London: To start, you came to art through the door of historical inquiry. You came to photography and collaging while living and studying in South Africa as an exchange student; and later, as a Fulbright Scholar, when you discovered an interest in the act of documentation and interviewing. I would love to know how you started on this interesting trajectory.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Thank you so much again for having me. In a lot of ways, I think there was always something sort of percolating under the surface when it came to wanting to make art, but not really knowing what medium or what sort of language or logic to use. When I went to Cape Town in 2005 as an exchange student, I was in the Arabic studies department, criminal justice, and sociology, and I really enjoyed all the studies there. But I was looking for something else to do other than writing an essay about what I was exploring.

[Later] I reapplied to go back to South Africa, but this time to go to Johannesburg on a Fulbright grant, and everything that I expected to do when I got there did not happen. I thought that I was going to do all this deep academic research and come back and possibly, after teaching, do a Ph.D. program. At that time, I thought that academia was the main method for expression, or publishing for getting ideas out in the world, because I hadn’t seen what else I could do with my art practice.

While I was in Johannesburg, I ran into these groups of activists and they were protesting. And so I would just show up and start photographing and interviewing people. I just really love the social aspect of talking to people about what it is that they’re doing, rather than inferring from documents or inferring from other contexts. I just love the social element of going to a place, meeting people, getting to know people, talking to them about what it is they’re outside about, what’s going on in their lives. And then taking that as opportunities for me to reflect, but also for me to story or narrate my understanding of a given history through these encounters.

The practice of photography shows up because, at that time, I had purchased a tiny four megapixel point and shoot [camera]. It was my pride and joy. I was like, “I’m a photographer,” with my little old camera. I just had such deep joy in trying to work with the limitations of that camera. I photographed a lot of workers who were concerned about union issues. I photographed folks that I would meet on the street as I was going to and from different things. I just really love that way of getting to know a community through that. I think because of that, in so many ways I kept coming back. I’ve been going back and forth to Johannesburg since 2006; I go back about every year. That’s sort of how we started.

When I got back to the States, I enrolled in my master’s program at Stanford to be a teacher, because that’s still my thing, I like teaching. I taught for about five years, and somewhere midway through I was like, “I still want to teach and I like teaching, but I think there’s another sort of context or substrate for this to happen. I want to say something, but I don’t know if it is done through high school education.” I started to take on this opportunity to install work, make collages, trying to figure out my footing. If you fast-forward now fifteen years, we end up here, but there was a lot in the midst of that before we got to that. It really starts as just an interest in social connection, a desire to understand how people story their own lives.

Barbara London: You’ve got these two sides, or you’ve got many sides to your practice: you’ve got the images and you’ve got the words.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Mm-hmm.

Barbara London: I love that you describe yourself as a logophile, a lover of words, that you’re fascinated with the written word, it’s power, both to define and destabilize how we understand the world. I love also how you work on the page, on walls, and in public spaces to create associative arrangements of letters and words and shapes and invite. You call it an embodied and iterative reading process and encourage viewers to do the work of understanding. You don’t hand it over to people, you want them to work. The love of images comes through a kind of social practice; where does the love of words come from?

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I think that words and images have always battled each other, as a sort of interest of mine. I think at this point in my practice, I kind of think about them in parallel or overlapping in a lot of ways. As a young person, my parents were very clear about watching TV. We didn’t get to watch a lot of TV. The music that we listened to was carefully curated.

We spent a lot of time with books. We would spend a lot of time at the libraries, doing all of the summer reading programs. We would go to the Menlo Park Library, which at the time had this one room of deaccessioned books, which were basically books they had pulled off the shelf. My entire family would just go, and we would build up our library from these deaccessioned books. My parents were big readers, and so I feel like in a lot of ways I grew up in a very language-rich household. There were texts everywhere—books, flyers, newspapers. At one point my dad was throwing out newspapers, so we had all these leftover newspapers in the house. We had newsletters from our mosque; we had flyers from school.

I just got really interested in seeing type on a page. I was just sort of fascinated by the curvature of letters, the ligature, how something may have been partially erased or eroded over time. Because I grew up during the time when we were getting personal computers, someone had gifted my dad a computer. I think it was one of the early, early, early Apple computers; but we had had a Windows computer before. I sort of toggled between these computers, playing with all the typefaces and fonts. I would spend hours upon hours typing my name, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, trying to find every single font, until I settled on a font that I was like, “This is the font that best expresses my interiority.”

To this day, my relationship to words and to language is that I think that letters themselves are these characters. I find them to be expressive. I’m really interested in a letter not just as something that’s conveying information, but conveying more than that. I would also say that at the same time that I was learning to read English, my dad was also teaching me Arabic. Part of that experience was learning how to write from left to right, and then having these early morning sessions where I was writing from right to left. I think there was something very interesting to me about how language could show up in these very familiar Latin letters, but also show up as what just felt like these deeply whimsical shapes. I think that there’s that.

I think that because of that interest in language and seeing things on a page and being fascinated with the curvature of a letter, I quickly took on the opportunity to use the publishing center at my school. It was like a trailer. It was an older woman who had just paper and binding materials. You could either go outside and play at lunch, or you could make books. Obviously, I chose to become an author at six years old, because that seemed much cooler than playing outside. I would spend every lunch period. I published about six books before I left third grade. We had book readings, where adults came to listen to kids read ridiculous stories. Now that I think about how ridiculous that was, that adults showed up to listen to me, at seven, read a story called When I Was a Baby that which was two years prior to that.

I think there were a lot of people in my life, particularly adults, who were really encouraging this interest in language and text. At one point, I self-deputized as the handwriting coach, where I was teaching students how to correctly write their letters to meet the line. I think I’ve always just been interested in the visual sort of imagery of texts. And then when it comes down to meeting and other installation practices, that branches off. I think it really does start with the love for the beauty of the letter itself.

Barbara London: You’ve already talked a little bit about your father. Reading about you and your work, I gather that he had a big impact on your working process. Could you tell me how?

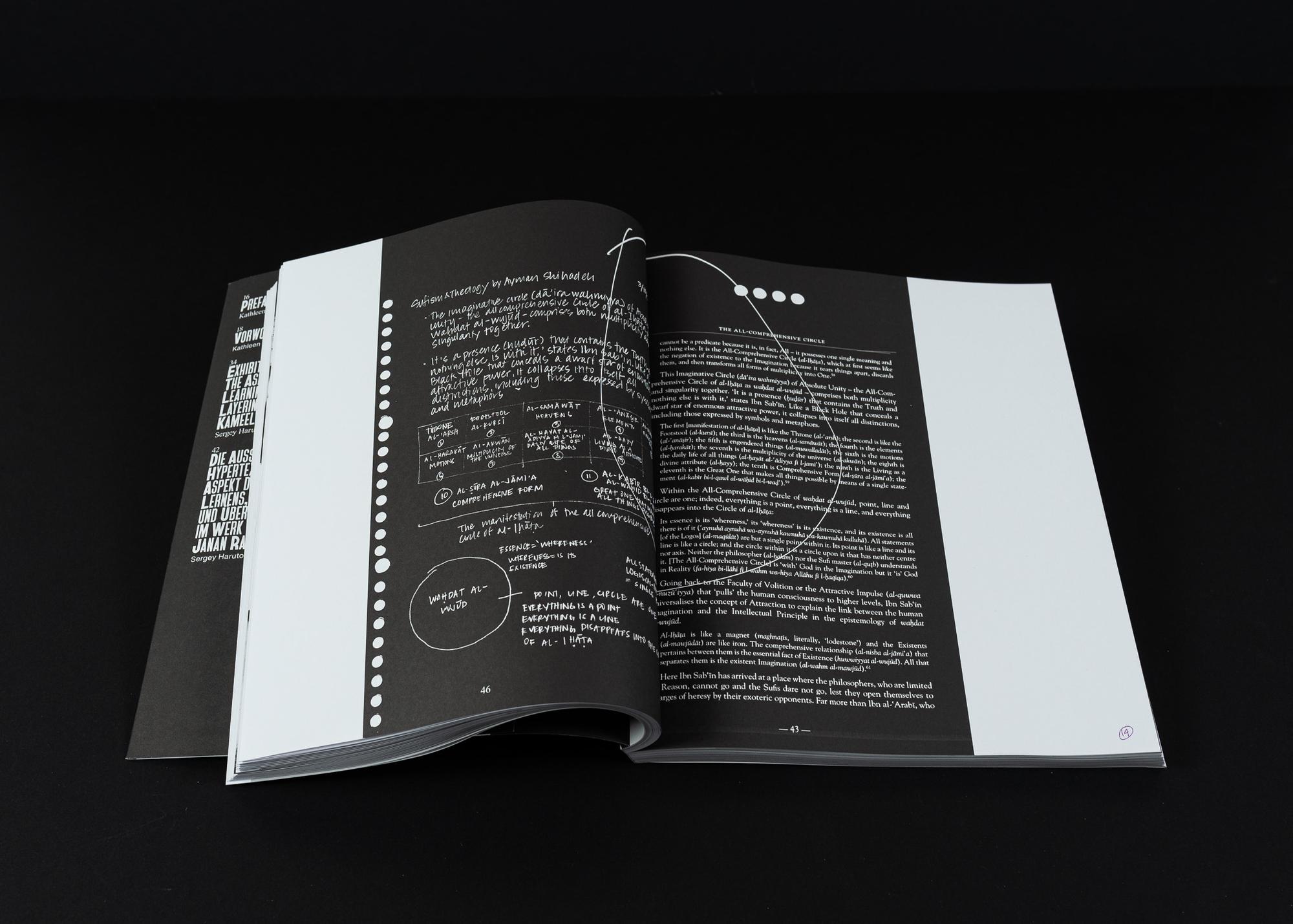

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I mean it’s purely accidental, if I’m being completely honest. I had always seen the notes and things that my dad had left around the house, when he was converting to Islam in the early 1980s. He was also in a pharmacy school, so he would basically flip over his pharmacy notes and type out his Islamic studies research and notes, which would include his handwriting in Latin alphabet, and in Arabic writing. Then he would photocopy excerpts with the Quran and paste them and then annotate them.

Maybe a decade and some change ago, I found the burgundy binder that I had, a glimpse of memories of when I was younger. As the family archivist/thief, I took it and I was like, “Dad, I’m taking this. I’m rescuing this. I’m taking this, where something’s going to happen with it.” I spent a lot of time pouring over it and being fascinated by how my dad was going through this very particular learning process, where he was annotating, redacting, and building up this layered field of texts as his learning process.

In 2019, I published a book. It was a republishing of the same book that had a printing error. And we did something different with the interview in the text. I basically annotated, cut out things, and basically created all this marginalia. I didn’t think about it. I was like, “This just makes sense to me.” I was giving a lecture at Brown and one of the students was like, “To what extent has your father influenced your practice?” I was like, “I didn’t even mention him. What does my dad have to do with it? Where is this coming from?” She gently said, she said, “Just go back a few slides.”

It was literally in that moment that I had recognized sort of this passive consumption and exploration of [how] my dad’s work deeply influenced the way that I thought text should show up on a page, that it shouldn’t just be sitting on a page in a linear fashion, that it should have depth, literal depth, there should be layers, there should be overwriting, underwriting, there should be evidence off change over time. In a lot of ways, I think that my dad’s process of conversion deeply influenced the way that I sort of think about and thought about learning as it relates to language, and how we leave evidence or traces of that through our annotations and marginalia.

I would be wrong not to include my mom here, also a very big reader. She would get through multiple books in a day. It was fascinating to watch this woman sort of speed through books. I remember this very clear practice she had around dog-earing pages, and becoming also really fascinated by that crease in the page or the ways that she indicated importance as she read. I remember her handwriting deeply too, when she was writing notes for school or even when she was correcting something of mine. In a lot of ways, my art influences are very vernacular and family based, but that awareness has not shown up until more recently when I actually am asked, who your influences are. And people will point to other people. And I was like, “Well, it’s kind of my dad and my mom and this random newsletter that my mom published in 1998.” These are all the deepest influences for how I think about how language shows up on a substrate.

Barbara London: You’re very lucky to have that rich culture growing up with family. I don’t think everybody does. You’re very lucky.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I feel very lucky.

Barbara London: Knowing we were going to have this conversation, I’ve been reading about your work. I love the title of your recent catalog, i am not done yet.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Mm-hmm.

Barbara London: It’s very dynamic and the publication is very inspiring. In the catalog I really enjoyed the transcript of your interview with Legacy Russell. It’s quite illuminating. There are a couple of words that are fascinating. One word you use is nothingness, and that’s an abstract term that the writer Professor Ashon Crawley describes as this dance between moments of opacity and transparency. How does this idea of nothingness fit into your work, given now what we’ve just discussed?

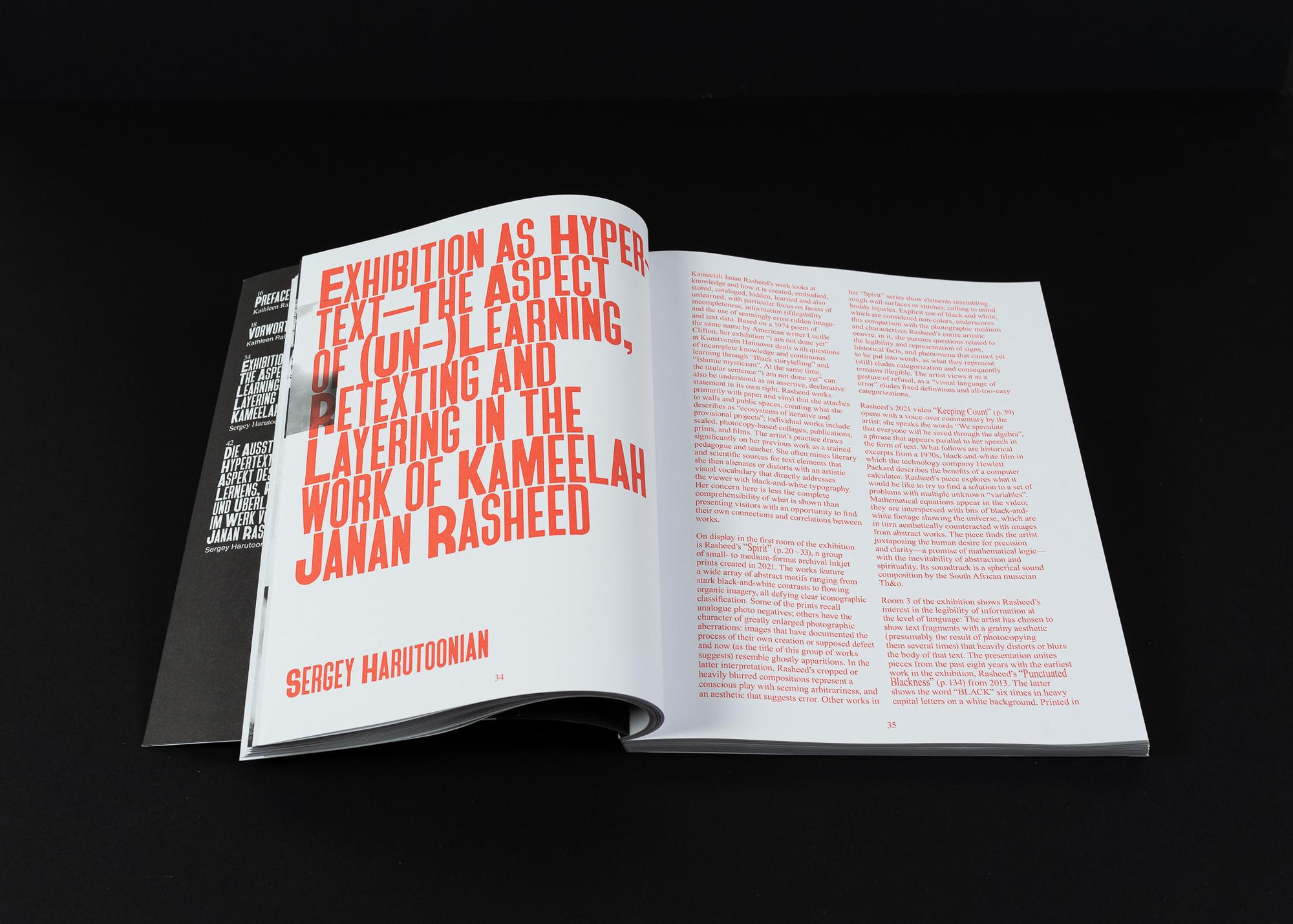

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I make a lot of books, but this one was for the 2022 show at the Kunstverein in Hanover. That was an amazing opportunity. They gave me the entire museum, so I had six halls to myself to sort of play in, which was great. The title of this publication comes from a poem by Lucille Clifton, a black American poet who has really transformed the way that I think about relationships to language, because of the way that she plays with language, engaged with ancestors and spirits in her writing process.

In this poem, i am not done yet, she has this very clear language around [what] she says, “As eminent as bread.” I think that there’s something about making work or just existing as a human being, where the goal is not to sort of reach a point of finality or completion, but to always be on the cusp or always be in an anticipatory sort of context. I think that there’s a certain point where if you are done, then what are we here for? I like to get up every morning and say, even on my worst days, the thing that makes me get up every morning is the possibility of learning something new or the possibility of figuring out something about myself.

2022

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

Mouuse Publishing

Book display photo credit: Sven Michael of Studio S/M/L

2022

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

Mouuse Publishing

Book display photo credit: Sven Michael of Studio S/M/L

The poem means a lot to me in terms of my many prayers around the importance of not settling too quickly into a belief or into an idea or into a practice, but allowing yourself to be eminent rather than have a particular role. Instead of being like, “I am X,” I sort of take on the language of, “I am a learner,” which gives me this expansive context of being on the cusp of being eminent versus having been an expert.

The context of nothingness comes from this essay by Ashon Crawley that he wrote in 2016. It is such a beautiful essay, and I’ve read it over and over. It’s an essay that is dense in a way that is beautiful and makes me so excited because I always return to it and find something more. The thing that struck me most about that paper is that he references a very specific example of the Bilali Document. The Bilali Document was a document written by an enslaved; I think he was a Fulani man in the south. Tons and tons and tons of folks have been able to translate most of it, as Ashon Crawley reminds us. There are five pages, he reminds us, that people have not been able to translate. Some of the issues have been like, “Oh, because he was an African Muslim, that his Arabic was just really poor Arabic and so maybe it’s gibberish,” or that, “There’s just nothing there.” There’s been this language of, if I can’t penetrate and analyze it, then there’s nothing there.

Ashon Crawley takes up that concern to say that nothingness becomes sort of this black hole where, because I can’t imagine, because I can’t see it, because I can’t access, nothing must be there. He sort of offers nothingness not as a lack, but as a space of productive and generative incoherence or as a space ripe for possible investigation or inquiry. It’s not about there being nothing there. It’s about our perceptive technologies and to what extent we have them. Also, he poses this question around what other relationships can we have to texts, to language, to existence, to people, to ideas that are beyond comprehension. I think he notes, “Can I look at a piece of text that is not comprehensible to me and find beauty possibly in the sort of markings of the text and sort of the curvature of the letters, finding something other than meaning in the reading process?”

This sort of dovetails well with some things that Harryette Mullen talks about in an essay that she writes about African spirit writing. She talks about the sort of relationship to writing, always needing to be in the context of rationality or comprehensibility. I think they dovetail well in saying that there are times where the writing is not for everyone, so you’re not supposed to translate it, possibly. There are times where the writing performs a role that exceeds, that is extra comprehension, where the comprehension may not be content comprehension as much as a comprehension of oneself as you sort of make sense of why you’re interested in that text itself.

When it comes to my own practice, I think that being an artist who, I like to say, I like to make my weird little projects and play in the corner, not as a refusal to engage with other people. But I think that there is consistently a pressure in one’s art practice to make everything legible, to make everything finished, to make everything polished, to make everything have a tight elevator pitch.

I think that when it comes to this language of nothingness, I sort of embrace it as an opportunity to encourage or invite people to think about other relationships they can have to my work or to have durational relationships. The durational context comes in as the first time you may encounter something; it may feel like nothingness because you can’t get everything that you want now. You can’t squeeze everything out, you can’t extract everything. I do think that through durational engagement, like repeated and iterative explorations of the work, something else is happening. I think nothingness is almost in some ways like a Trojan horse in a way of, if you perceive this as nothingness, if you engage with this as nothingness, in what ways can that be useful in helping you develop a different relationship to information in the world? Also, is there a sneaky way for me to think about other possibilities through the perception of simplicity or through the perception of absence?

Barbara London: There’s also another factor in there that sometimes we’re not ready.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Exactly.

Barbara London: We could say, “I don’t get it,” and then you go back to it.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I’ve spent the majority of my life in education. I was a high school teacher, and then I went to curriculum development where I was coaching high school teachers; and then I went into post-secondary teaching, where I am teaching again. There’s a pedagogical edge to the way that I relate to my own practice, where what I was learning [about] how to become a teacher and sort of going through this process, we were always reminded you do not give students the answer. You can take them on a quest to help them discover on their own. We can set up scaffolds to support their inquiry, but we don’t give them the answer because when you give someone the answer, they don’t have the actual embodied somatic into spiritual experience of having gotten somewhere.

I think in a lot of my work when I don’t complete sentences or I don’t finish a thought, it’s not me sort of performing difficulty, as much as it is me saying that I actually want to collaborate with you in this sense. Maybe I don’t know how to finish that sentence and I’d be so curious to see how you would finish it. I think Pope.L talks about this a lot when he, may he rest very, very radically and peacefully, when he talks about whole theory. I find [in] that text there are parts that I understand, parts that I don’t understand, but I think the part that resonates the most for me is [when] he talks about holes as occasions and opportunities. I like to think about having holes in my work, not as performative, but as opportunities for intervention and collaboration.

In his video interviews for his hospital show in London, he says, “I’ve left a lot of holes in the show and I want you to fill them in with your experience.” For the past year whenever I’m teaching, I’ve included this because I think it’s such a beautiful reminder for artists, for writers to think about what space is there for the reader, what space is there for the viewer? If I take up all the space with everything, you can’t hear yourself. I have to figure out a cadence and a pitch that allows for me to be heard, but at the same time doesn’t speak so much over the audience, or so much over the reader, that they can’t actually be part of braiding a story together.

Barbara London: There’s another word that came up in your catalog, i am not done yet, and that’s destabilizing. It’s very related to what you’re talking about because you’re enacting, you’ve got the act of repetition and layering as part of making what you’re just saying possible.

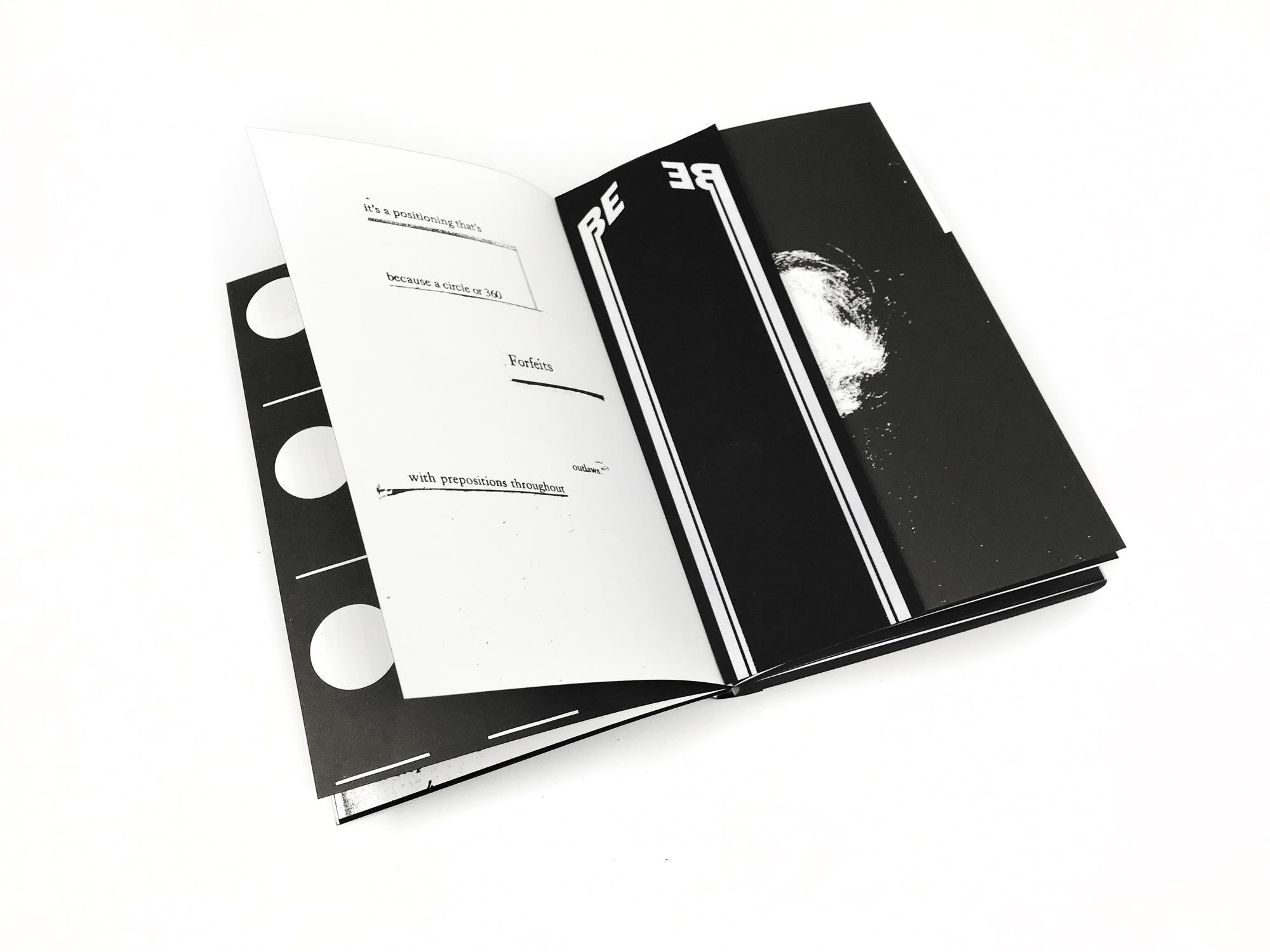

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Mm-hmm. Yeah. I will relay a story. In 2018, I published this book called No New Theories, and it was with Printed Matter, [and] that was a dream. I came to New York in 2010 and said, if I could just volunteer for free at a Printed Matter book fair, I’d be the happiest person in the world. When they approached me about a show in 2017, I was really excited. When they approached me about a book in 2018, I was very excited, and now I’m on the board. There is a sense of joy. I was like, I made it past being a volunteer but…

2019

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

Printed Matter, Inc.

I mention all of this because the first edition of No New Theories had a series of printing errors. Prior to that occurring, I had been talking a lot about incoherency and revision and public learning, and all of these very sexy concepts: revision and opacity and all these things. Then I had the actual opportunity to live the thing I was talking about, [and] I could not deal with it. I was like, a book was misprinted, pull every book off the shelf, burn every single book. Something of imperfection has gone out into the world.

In the summer of 2018, I had this very clear, not so much an existential crisis as much as this very clear moment where I said, “Hey Kameelah, there’s intellectual understanding and there’s spiritual and emotional understanding, and these are not in relation at this point.” I really had to do something with myself, because it was a deeply destabilizing moment. I had a choice of either trying to pretend this other book never existed, or actually leaning fully into it to think about what could happen, when a particular belief or a particular filling or a particular set of processes are destabilized for you.

Part of that experience was republishing the book in 2019. In the republishing of the book, the way that it was typeset was that there was the court interview and then there were a series of annotations, much like my dad’s notes. For me, destabilization is metaphorical, that sense of literally feeling destabilized as you’re sort of going through an experience. I think also in terms of the book itself, having encountered Espen Aarseth’s Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. There is an interest in ergodic literature, in that it actually asks for the reader to do something, as he says, “Other than just moving their eyes back and forth.” I think about destabilization as a somatic and corporeal experience of how do I create a reading experience that may in some way mimic that sense of many things coming at you at once, which is how my brain sometimes feels, but also what does it mean to have a sentence that is consistently being interrupted by other thoughts, as a reminder that we almost rarely get to finish a thought without other destabilizing factors coming in to sort of move that around.

For me, I think about destabilization as a pedagogical tool. I use it a lot in my teaching, particularly if a student is saying something or I’m saying something and I’m like, “Now we got to kind of fight about this. Let’s fight, lovingly fight.” I love a good argument. I love a good fight in my class because I think that discomfort has helped me grow so much. I think very carefully calibrated discomfort is very generous. I think about destabilization discomfort within the same context. I think that I’m interested in destabilization as a neurodivergent person, because so much of how I move through the world is about me constantly trying to calibrate with systems that are not well calibrated to me. I’m constantly trying to find some sort of balance. I think that now as I’ve gotten older, the stabilization and the destabilization have become more generative than painful. I sort of like to lean into that as a productive spiritual force, as productive artistic force. I like the vibration as a reminder that things are buffering and coming into form versus already in a final form.

Barbara London: I read something where you said that your work exists as a kind of performative score. But when I’ve looked at recordings of you giving lectures, which are as remarkable as our conversation, you’re very performative. I’m interested in that, in the middle of our topic of performative.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: What’s funny is, I think I would often say, “I would never do performance art. That’s not me, that’s not who I am.” I think that in a lot of ways that is exactly what’s happening by accident. I would like to argue for myself that the things that I think I do the best, are the things that I come at at an unconscious angle. I think the things that I put my brain to like, “Yeah, I’m going to do X, Y, and Z.” And they don’t turn out as well as the things that I sort of fall into. I don’t think that I would ever call myself a performance artist, because I don’t think that is a register that I’m aiming for. But I think that my work has to be performative organically, because so much of how I think about my practice is about social discourse and social interaction.

Whenever I have an exhibition, I also plan the public programming with the same rigor and same excitement and same sort of attention as the work in the show because I do think about them as being in relation. I think about public programming as another context for contextualizing, but building relationships between people, building relationships between ideas. I think about it as a form of aftercare too. I do think often about museums and galleries and aftercare and pre-care; what does it mean to leave an experience but not have a space to hold you after that, to either talk about it, release, or whatever the case may be. I think that shows up.

I just think also, by the choice of being a high school teacher, you are a performer. I think it’s the best improv. It’s the best improv training you’ll ever receive because you could be giving a lesson on the Punic Wars and someone has a breakdown. And you have to figure out how to manage that breakdown and continue this lecture about the Punic Wars, and make sure that no one goes out of the class when they’re not supposed to, and make sure that the bathroom pass is where it needs to be. I think that I just got very good with this process of entertaining multiple things at once. I also grew up with four brothers, so I think I’m used to improv. I think that teaching is improv. I just think that’s what it is. I took an improv class in 2020, I think it was, and I was like, “Oh, this doesn’t feel difficult.” I was trying to figure out why, and I was like, “Because girl, you do this every day.”

I think that that element of it, but maybe this is a very basic thing to say, I just really like talking. I think as evidence, I really like talking and I really like listening, and I really like what happens in unplanned conversations. I just think there’s a certain magic there when people are just talking and they arrive at things and you leave the meeting saying, “Dang it, I should have recorded that.” I think those are the best moments. I think, yeah, I like that. Yeah, I feel like socially, I’m not like a person who goes out all the time and does all this. But you could put me on the stage in front of a thousand people and that feels easy to me. Or you could tell me to go to a party and I’ll be terrified.

There’s something about the framing of the stage, the framing of audience interaction. I did stand-up comedy once by accident, and then I was invited to do it for real. I was giving what I thought was a very, very, very serious academic lecture. It was about these very vernacular advertisements in South Africa, and there was an Irish comedian in the crowd who was like, “You should do stand-up. That was really funny.” I was like, “I was not trying to be funny. I was giving a very important and serious lecture.” She invited me back. I finally got back on the stage in 2016 and I did an eight-minute set, and it was exhilarating and amazing. And I did crowd work, and it feels like a very comfortable context to be in.

Barbara London: Maybe before we move on to a last thing, museums are very special places. People might knock them, but they’re environments for work like yours and environments for an artist like you to engage with an audience, because everybody who goes to a museum doesn’t know everything. I find it to be quite beautiful to have your work and to have you present to talk with people.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Sometimes I hide at my shows. I’ll go to my own opening and sort of hide in the back because I am interested in the dance that people do with the work of moving close, moving back, trying to find the right angle. I am sort of witnessing the dancing with the work. I think maybe this goes back to a question either I saw or that you may have asked and I didn’t answer around performance scores. The way that I design my installations is very intentional, in that I’m interested in how the body is implicated in a viewing process. I’ll often organize things conceptually, but also architecturally to sort of think about bodies and space. Having something in the corner that pulls you to the corner so that you can sort of snuggle on the corner, having something very small next to something very large, so that you are literally using your body to zoom in and out. Having something that’s floor based, having something that’s closer to the ceiling, but to sort of stretch your eye and body across the space.

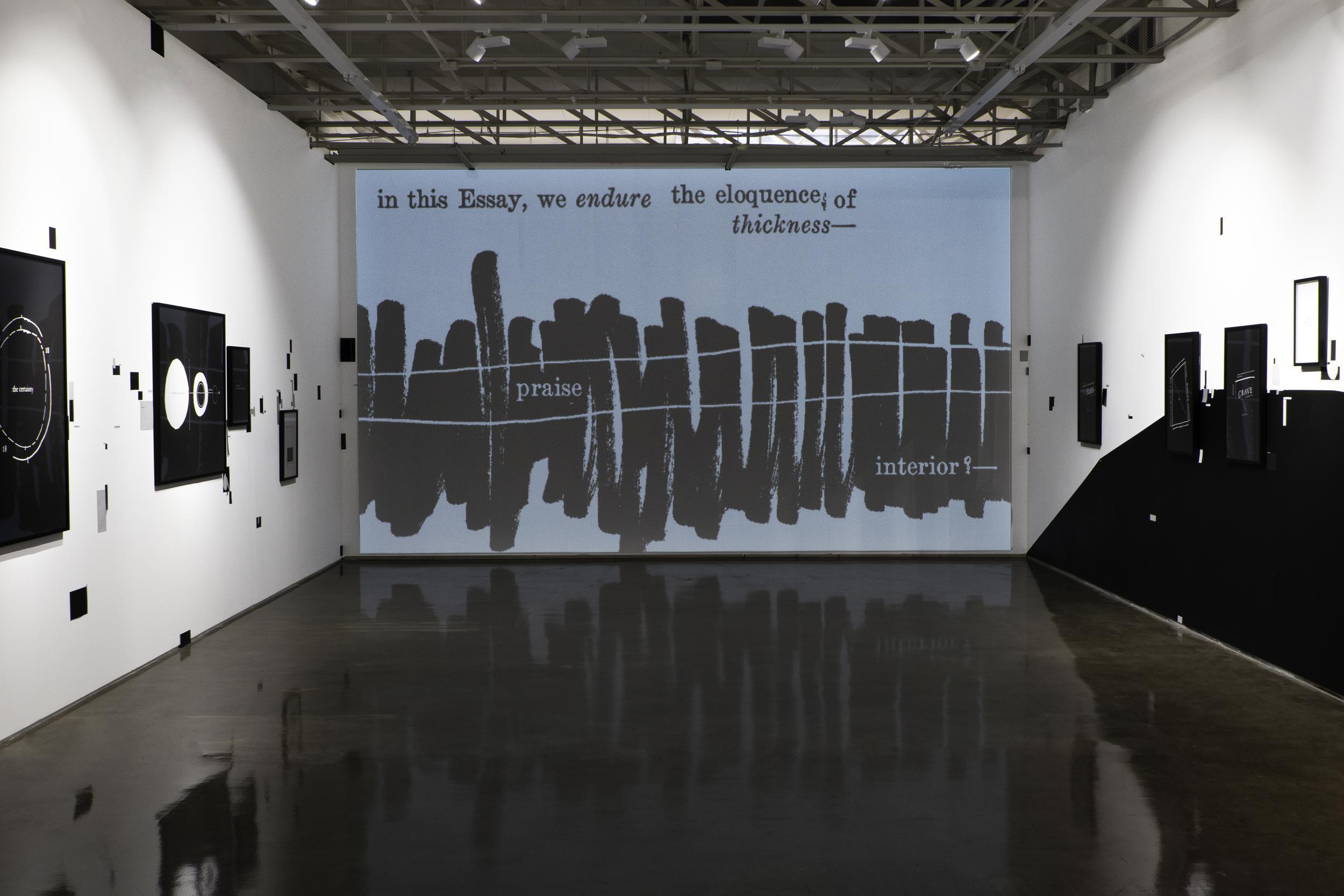

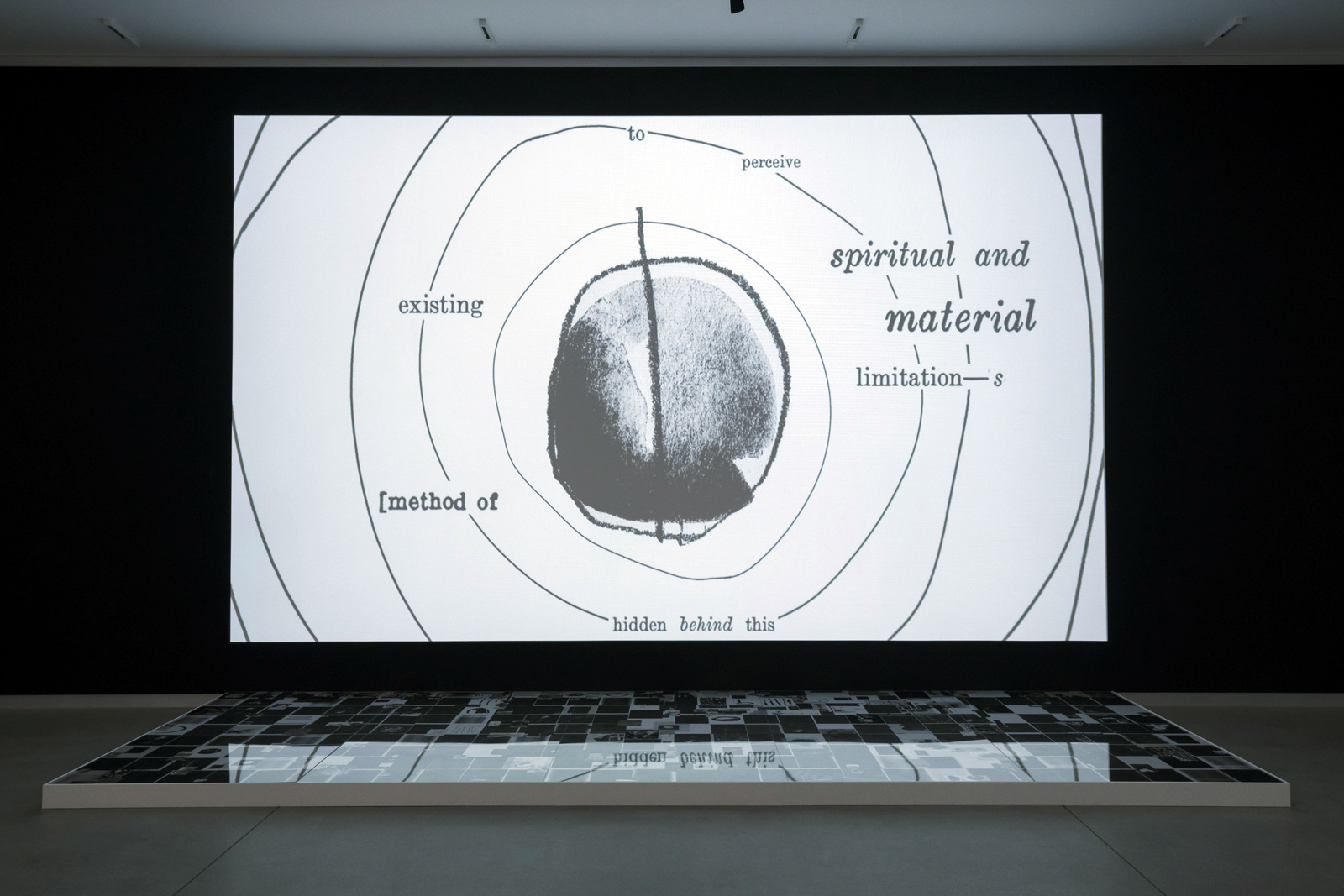

Barbara London: You’re not known for doing videos, but I did see your video work called Keeping Count. How did the video come about?

2022

Single-Channel Video

00:04:13

Original Score by Th&o. (Johannesburg, South Africa)

Film Excerpts (Prelinger Archives): Computer Calculator for Math and Science (Hewlett Packer, 1970s); Your Chance to Live: Earthwatch (U.S. Defense Civil Preparedness Agency, 1972); Frontiers of the Future (National Industrial Council, 1937); Some Fruits We Like (Unknown, 1920); Above the Clouds in Rainier National Park (Unknown, 1920); Basic Typing, Part I: Methods (Part II) (U.S. Navy, 1944)

Hand and Digitally Edited 35mm Film Trailer Teasers: Meteor (1979) The X-Files (2008)

Keeping Count

Keeping Count2022

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

Install shot at the Piero Atchugarry Gallery, 2021

2022

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

Install shot at the Benton Museum of Art, 2022

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: I did this thing when someone asked me about a show. I was like, “You know what? I’m just going to try something new and I’ll figure it out along the way.” I had taken a Premiere Pro class for a day or two, but got bored very quickly, because that’s what happens when people are giving very, very mundane instructions. I just zone out. I learned a little bit and I was like, “I think I could figure this out.” The video came about because I had this show in Miami, it was in May of 2021, and I said, “Oh yeah, I’ll just make a video.” Maybe this was foolish overconfidence, but I was like, “I feel confident that I can figure this out in time for this.”

A lot of what ended up happening is that I almost sort of figured out my own sort of logic or vernacular for how I approach video work. I quickly realized that I’m not interested in doing live shooting, I’m not interested in that element. I figured out quickly I wasn’t really interested in narrative at all. What I found very quickly was that I was interested in the politics of layering, and I was interested in thinking about collage, as well within that context. The video came about because I had a previous series called Casual Mathematics where I was thinking about the relationship between data, liberation, theories, and blackness in terms of thinking about how do you calculate or approximate a point in the future, or how do you calculate or approximate the amount of dehumanization? Is it quantifiable? AI had all these works that included the intentional misuse of mathematical and scientific language and signage to sort of empty it of the numbers necessarily, or the symbols, and to include texts and sort of one of these other poetic fragments.

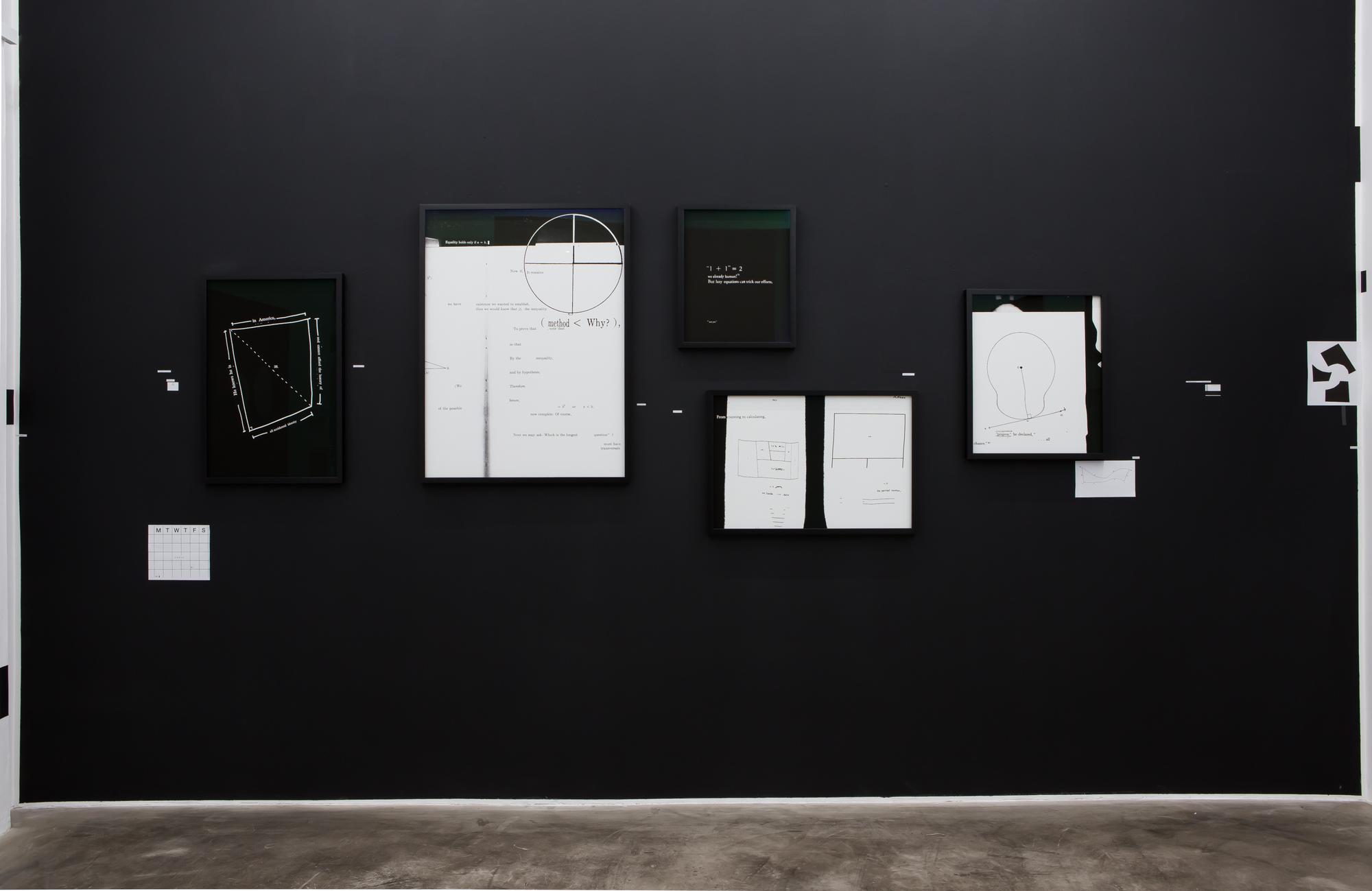

2019

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

NOME Gallery

Photo credit: Billie Clarken

2019

Kameelay Janan Rasheed

NOME Gallery

Photo credit: Billie Clarken

For the video, I wanted to make something that spoke directly to that work without being redundant. I knew that it couldn’t be another print, but it actually had to be something moving. The way that I approached it, because I was a novice at Premiere Pro, is that the animation you see in the video I did by hand. There’s a thing called After Effects that you can use that creates movement. I did not use that. I basically said, “Here’s a line of text that I want to include. I’m going to create a mask for every 13 seconds and move that mask over in Premiere Pro to create this animation.” It was a slow, tedious process. It was like 70 layers of tracks in Premiere Pro. I found it to be a deeply beautiful and meditative practice of sitting and trying to build a world, not so much through this horizontal process, but through this vertical process of literally building these geological layers.

I think about video production as geological layers of how a core sample works. You’re building these things on top and that there are different opacities to these different levels that allow for a certain image to come through. I worked a lot with some of the found footage at the Prelinger Archives. I worked with some of my own handwriting. I worked with a range of things. In the credits, there’s a whole list. I also got some film from eBay, which were just sort of like these reels, like the actual plastic film. I would scan them in in a regular fashion. I also took leader film and painted directly on them and photographed them using a film scanner while shaking them at the same time.

There are all these different methods that I had taken from non-digital practice that I wanted to translate into this. I think that translation shows up a lot in my practice as I’m like: I made a photocopy, now this photocopy becomes something digital. Now this digital thing now becomes a projection. Now the projection now becomes a textile. I like sort of moving the same thing across different substrates and contexts and seeing how sort of the artifact from the previous thing gets carried with it and becomes part of the content itself. That’s how the video came together.

My best friend, Thando Kunene, who is a amazing music engineer, human being, best friend in the world, he provided the score. The funny thing about the score is that I sent him my voice saying things and said, “Just respond.” I didn’t expect my voice to be in the video because I don’t like hearing my voice back, which I’m saying as I’m doing an oral interview. I mention all that to say that it was a collaborative work in that I think the score did so much to illuminate the work that I could not see that work without the score. He’s been my collaborative partner for all of my music scores forever. I hope, as he becomes more and more famous every day, I hope that he doesn’t forget about me and continues to work with me.

It was a fun experience and I really like challenge-based work. I don’t want to do something that comes easy to me. I want the challenge of working with a new medium or a new process. I want the work to show that I’m learning and not to show that I’ve learned, if that makes sense. I want the work to show learning in process. I’m sure you can go through there and find tiny errors or moments where things wouldn’t look the way that I may have wanted. I just couldn’t figure it out, but I was okay with leaving them in there because I think I’ve gotten to a place around public learning where I think it’s important, particularly as an educator for younger artists, to see what learning publicly or learning out loud looks like, and that you can have drafts of things, you can put drafts into the world. Everything doesn’t have to be perfect, finished, done. I do love the video, actually.

Barbara London: No, it’s very special and you’re very special. I think you have so many wonderful projects, and we haven’t even touched on some of the other things you do like the Orange Tangent study, a consulting business. You have Black Orbits, a platform for digital archives, exploring the many permutations of black life through the material and the immaterial. You’ve got something called Scratch Disk Full, a project of publishing leftovers, excess, dirty data, spillage, and the unfulfilled, I don’t know how you decide where to put your energy.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: It is a consistent concern of mine. I think that I feel like from 2018 to present, I’ve been doing all of this very specific neurological, psychological study of myself because you live your life and there’s so many things that you do and you’re like, “Well, everyone is doing this.” Everyone is juggling fifteen different tracks of stories and interests at the same time, and everyone is being obsessive and everyone’s doing all these things. And you actually pull back and you say, “No, that’s just you.” I think that in this sort of journey to better understand my own neurodivergence, what ended up happening after this very specific mourning and grieving process once you realize everything you suspected about not being within the typicalness. What I tried to do with that was instead of being sad about having such a diverse interest in a lot of things, instead of being sad about being obsessive, instead of all these things I said, I could just use all of this very unspent energy that is already running inside of me to make things.

Orange Tangent Study is a consulting business, but at the end of the day, I really just want to give grants to other artists. When I get a client, I put a little bit aside, and then that money becomes money as microgrants for other artists. We have an application round that just closed. We’re giving three artists $1,275, and there’s one that’s reserved for artists over the age of fifty, because I was looking at gaps in grants.

I have clients, I have fun with them. But really, I just like giving money to other artists because I think that there are so many people who have great ideas but don’t have access to resources. If I can give you $200 for you just to get the supplies for you to test something out, I’m not a gatekeeper. I want everyone to make their art, and I want everyone to get their stuff out there. I think that they’re probably amazing masterpieces in people’s studio and they don’t have a space to show it, or they don’t have the money to get it framed. I kind of want to close the gap between an idea or a desire and resources.

Black Orbits is a project that’s come out of a lot of desire to think about archives. It includes one archive called Mapping the Spirit that’s already live, which is looking at black religious experiences, but not so much at belief systems as much as itinerancy and movement over time. It’s not about beliefs, but it’s about self-revision in the spiritual journey. There’s another one that’s going live next year, which is black vernacular photographs. It’s an archive of about 4,000 black vernacular photographs that I’ve sourced from a range of places over the past fifteen years. They’re sort of released to the world as these sets that come along with an essay by a writer. They come with an interview from a family member related to the theme.

The first one that’s coming up is pets. So, there are a bunch of black vernacular photographs of black folks with pets. My mother grew up with tons of pets. I didn’t even understand. She grew up in LA and she had rabbits, she had birds; she had all kinds of pets. She’s an avid bird watcher now. She wouldn’t call herself that, but she loves watching birds. I’m interested in this angle of black folks in nature, but not just like in nature, but this relationship to other species.

Then Scratch Disk Full actually got reincorporated under a different project called the Little Octopus School. The Little Octopus School is a school for people who have eight tentacles that are reaching for everything simultaneously. All of our classes are sort of niche interest classes. Literally, I’m doing a class right now on Clarice Lispector, where we’re reading her book slowly and talking about it, Água Viva [The Stream of Life].

Next year we’re going to have a club called Info Dump Club, which is for people who info dump frequently but may not have a consistent audience for it. I’m kind of calling it matchmaking, too. I think that more people should be matched with people who also have weird niche interests. You get seven minutes: you come in, you can hang out, you get to info dump, and then you get paired up with other people so that you can do speed info dumping. My dream is to create a dating platform that is organized around info dumping. I think that that’s how I’m going to find my partner, through info dumping: who has the best info dumping.

Scratch Disk Full is the imprint under the Little Octopus School, where it’s basically any random obsession you have that doesn’t sort of fit within the contents of a show or a future publication finds a home there. We do publications. There are games that I’m working on. I made a publishing game that determiners for you how your book will look, how it’ll be distributed. I’m working on some other games that sort of are across between Sudoku and Kakuro, which are both Japanese games. Kakuro is a math one. They’re both numbers based, but Kakuro is arithmetic arrangement and Sudoku is a logic game with numbers. I just like games and making things for people to come together to have fun.

Barbara London: You’re pretty amazing, I have to say. I was going to ask you about the title of your upcoming Yale course, “The Word is the Fourth Dimension.”

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: That actually comes from Clarice Lispector’s, Água Viva. She is talking about her writing process and she makes all these announcements about how writing is a lot of phrases. It is hard because you’re trying to grasp something that’s out of reach. She has this one sentence where she says the word is a fourth dimension. It is organized around artists who are engaged in text-based practices, particularly installation artists who work with text. The fourth dimension is sort of a way to talk about our relationship to space and duration. In the class, basically we will read Água Viva in the background. We’ll read a couple pages every week and discuss. Then we’ll also be doing a series of projects throughout the semester, looking at these different artists who are engaged in text-based installation practice.

Their final project, as I have conceived it today, it probably will change tomorrow, is that everyone is going to write an ergodic essay, either in a browser or in printed form. I forgot to say that I do a lot of coding. I also want to integrate what it means to think about reading on a browser versus on a piece of printed matter. We’ll explore all substrates. They’ll have a project for writing on paper type substrates, writing on the browser, writing in physical space, writing on architecture. We’re going to get at all the substrates. We might even bring in a tattoo artist to sort of think about what does it mean to write directly on skin, as a porous substrate. I just like teaching and having fun and making weird projects.

Barbara London: Well, you’re pretty amazing. It’s wonderful to talk with you, and I want to thank you for joining me.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Thank you so much. This was great. I really appreciated that. We got to talk a lot about ideas. I do conversations that are almost sometimes so much focused on the art. I’m like, “No, there was weird story I really want to tell you.” I appreciate being allowed to go off on a couple of tangents. Yeah, thank you.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Ryan Leahey, with audio engineer Amar Ibrahim and production assistant Sharifa Moore.

Support for Barbara London Calling 3.0 is generously provided by the Richard Massey Foundation and by an anonymous donor.

Special thanks to Masayoshi Fujita and Erased Tapes Music for graciously providing our music.

Thanks to Independent Curators International for their help with the series. Be sure to like and subscribe to the podcast so you can keep up to date with new episodes in the series. Follow us on Instagram at @barbara_london_calling.

Web design by Sol Skelton and Vivian Selbo

This conversation was recorded December 10, 2024; it has been edited for length and clarity.