Barbara London: Today I’m speaking with Brooklyn-based artist, Matthew Ritchie. Born 1964 in London, Matthew received a BFA from the Camberwell School of Art, before he moved to the United States in 1987. He works in installation, painting and public art, drawing from ideas as varied as creation myths, particle physics, thermodynamics and art history. His artwork has been shown around the world, including in the Whitney Biennial and the Venice Architecture Biennial. It is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Matthew, thank you for joining me.

Matthew Ritchie: Such a pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Barbara London: For starters, tell me about your upbringing in the UK and your move to the United States in the 1980s. Do you feel a connection or a disconnect to where you’re from and where you are now?

Matthew Ritchie: Oh, such a lovely question, especially given the title of this podcast. Because of course, I grew up in London. As a kid, we got to see “Top of the Pops” with David Bowie, Marc Bolan, the glam rock explosion followed by punk, new wave, the Clash. Their song London Calling is like an anthem from my generation, really.

To be honest, I did not love London, but by now I’m a bit older, I feel how lucky I was to have lived through just this incredible sequence of cultural shifts. It wasn’t really anything I could understand at the time. But the British Empire, that cruel and obscene entity that once ruled a quarter of the world, had collapsed. And it was the 1960s, when it really was in its death throes. And it was being replaced by something called the Commonwealth, which was a made-up effort to apologize for centuries of absolutely appalling behavior.

And as a result, this was a real rare pocket, I think, in history to grow up inside. It might well have been naive or false on lots of people’s parts, but to welcome citizens of the Commonwealth in a really a last-ditch attempt to prop up the old residue of the empire. You had this incredible crossover of all these people migrating from India and Jamaica into London, at the same time as you had this other growth. And then you had a massive economic collapse. These things all conspired under a socialist government to both be a remarkable thing that began, that you could say, with the Beatles and ended with Margaret Thatcher and the Clash and The Specials singing “Ghost Town.” In between that, you had every possible version of what it meant to be an artist and a musician. All in a twenty-year lifespan, but I was a kid inside. I grew up inside that on the outskirts of London. It’s one of those things you just don’t realize how lucky you are until it’s gone.

I look back now and think in many ways, that completely shaped me; that openness to multiple cultures of syncretic thinking and the idealize notion of internationalism that was written about a little by a guy called Paul Gilroy, who wrote a book called There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack (1987) about both the consequences of imperialism and also, to some extent later, he would write about the opportunities in a global idea of music. We’ll get back to that with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and the opportunities in a global idea of music.

Barbara London: Was landing in the States then a shock? You landed in New York, right?

Matthew Ritchie: I first moved under this delusion, really, that the Commonwealth included Canada, so I moved to Vancouver Island. I was the fifth wheel in a very complicated relationship that involved multiple people, who were all splitting up with each other. And I’d tagged along for the ride. I got to Canada and I thought it’s going to be great here. The Queen’s on the money. They love British people. They did not love British people, especially in 1987. They saw me coming a mile away, and they were like, “How much money do you have?” And I was like, “I have $400.” And they were like, “Well, you can stay three weeks,” and stamped my passport. It was an amazing adventure on Vancouver Island, where at the time, they were then making something that was called BC Bud, which was hydroponic weed, an incredible new invention in the world. It was the strongest weed in the world, and there were all these people smoking it at the university.

Then three weeks later, (in a Cheech and Chong style cloud), I was ejected and took the ferry to Seattle, where there was no entrance examination. No one asked how much money I had, they were just like, “You’re in.” But it was jarring because Canada’s very clean and nice and uptight but organized, and then Seattle was just, at the time, pretty trashed. I got there, and by that point I no longer had $400, I had $250, being frugal. I got a Greyhound bus ticket, which was a one-way ticket across America for a year. You could stay on the bus. I was like, “This is a year of hotel rooms for $99,” as long as you kept moving in one direction. Some months later, after picking up some work moving across America, I got to New York. It was really literally the end of the ride; there was no further east to get to. A total accident. That’s how I got to New York.

Barbara London: You landed in New York and you started making art in New York?

Matthew Ritchie: What a lovely idea. It’s tough making art in a homeless hostel. It was a SRO; there’s not a lot of room. No, I was just pounding the pavement looking for a job. It was one of those times where, although I’d been waved in in Seattle, in New York there was an immigration crackdown. Suddenly, it was, “Show me your papers.”

I was lucky enough to run into an artist friend of mine from England, Matthew Radford, last seen in the North Peckham Estate, which was a notoriously disastrous estate where I lived in South London. He had disappeared from my life, certainly, and moved to New York. I ran into him, again an incredible fortuitous accident, stepping out of a door on my way to look for a messenger job. He got me a job painting storefronts in the South Street Seaport, which at that time was pre-Giuliani, so it was like cardboard boxes full of fish on the sidewalk. It was a terrible place, all run by the mob.

We were hired to paint over the grills with pictures of fish, to paint over the graffiti to make it look a little more user-friendly. It was such a lifesaver. I owe a huge debt to this guy for that. Through him, eventually I found my way into the New York art world in a very roundabout way, five or six years later, really by writing criticism for a magazine called Flash Art. Aptly named. Which I think survives as a website, based in Italy.

Barbara London: You’ve had a very rich career. That’s great to hear the beginning. I’m going to move on a few years and to a phrase you’ve called drawing, an infinite machine, a dictionary and a map, something at the heart of everything you do. It is a continuation, it sounds like, of that early job in New York. Drawing and painting is always there.

Matthew Ritchie: The college I went to in London [the Camberwell School of Art] was famous for a very strange form of teaching called analytical drawings. It was very British. It was founded in the 1940s. There was an influential teacher by the name of William Coldstream [1908-1987], coming really out of the Second World War. Analytical drawing was about exploring volumetric space through coordinates. You’d make all these tiny, little crosses, and then you gradually join them up and they would turn into a person. It was very exacting training.

What it had that’s quite special and unique was, it re-dimensionalized the flatness of mid-20th century abstraction and workbench abstraction that was the dominant form. It had survived at Camberwell through these ancient characters, some of whom had served in the Second World War, and vaguely referred to it as something they did on the bridge of a destroyer when they were drawing during the Suez crisis, or something.

There’s an empirical tradition in England that goes back, really, 1,000 years, separate from the main continental tradition that we know today as Occam’s razor. It’s about a rationalization of the impossible of imagination. Sherlock Holmes is the classic example of this bizarre idea that you can “detectivize” your way through reality.

And drawing is like a through line; it seeks to identify salient points in any continuum, in any dimension. I think that’s where it relates very strongly to music and mathematics. It’s the kind of common language, what some people have called a “semasiographic” space. In the inner drawing or a musical score or a mathematical space, you can go backwards and forwards in time, which you can’t do in a logographic space or a storytelling space. If we were to just randomly break up this podcast, run it backwards, it would become unintelligible. But you can do that with drawing and you can do that in mathematics and you can do that in music. You can rearrange a score and section it up.

I think there’s a way of thinking about space and time that those things all have in common that’s quite different from verbal intelligence. And that’s why I often refer to drawing as a dictionary. It’s somewhere where the old Babylonian idea that there’s numbers and there’s words and there’s pictures; they all fuse in drawing to be the same thing.

Barbara London: I love that word, detectivize.

Matthew Ritchie: It may be a first on the podcast. Maybe the first use of that in the English language.

Barbara London: It’s been fascinating watching your career, because we’ve known each other a few years. Over the years, you’ve worked quite extensively with writers, musicians, dancers, and scientists. You describe yourself as classically trained, but note a minimalist influence. Does that have to do with the drawing, that minimalist influence? What do you mean when you say that?

Matthew Ritchie: Well, I think there’s an amazing tradition that’s really centered on New York, from Brice Marden to Morton Feldman, this idea of the held space that inside which is where drawing can occur. That was completely new to me and one of the great revelations of coming to New York. The idea that you see that active line that travels into and also acknowledges the void that it’s in and understanding that that line, in a way, has to collaborate. It’s not just colonizing an empty space. Whatever is there actually has substance of its own. And you’re engaging in this back and forth. An American art historian would recognize it. They’d call it figure ground relationship, like Hans Hofmann, like push-pull.

But the tradition I came from didn’t really see it that way, so this was always really interesting… I’m still fascinated by it, and it’s like I’m slightly to the left of that understanding. It’s not intuitive for me. I always have to remind myself that the field is actually an invention, similar but quite different to, say, what Matisse produces in the Red Studio [1911], where you can see the beginnings of a field where it’s like the red is now almost like a sound; it’s almost alive. But as that progresses into American abstraction, it becomes something much grander and more sophisticated. And similarly with John Cage and American music, of Phillip Glass, Terry Riley. You get this huge spectrum of sounds that really hold notes and think about them almost as phrases, but always inside this enormous other space. To me, that’s a very different thing than, say, Iannis Xenakis. He’s almost ornamenting space and time rather than just accepting its immensity.

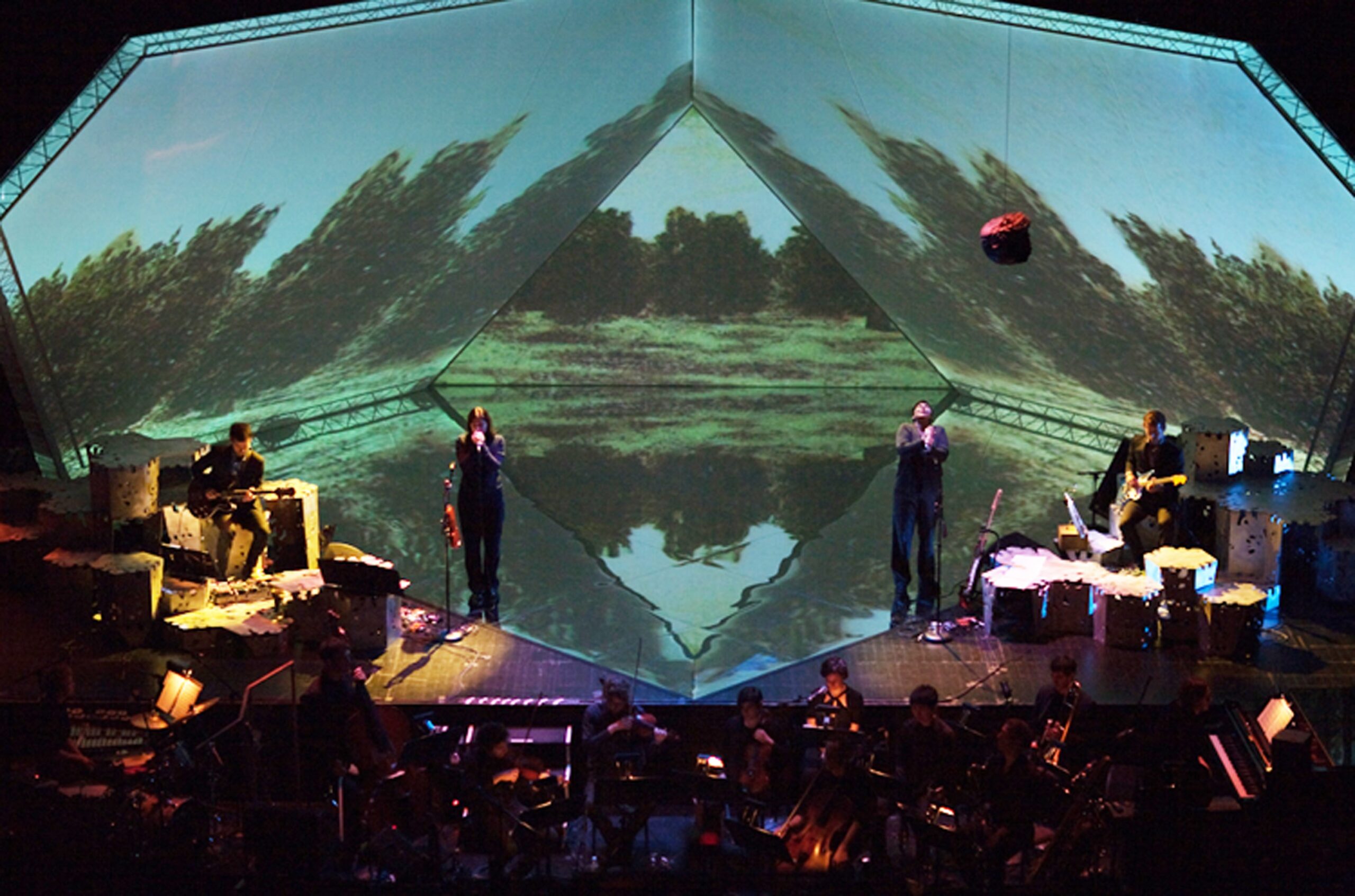

Barbara London: Let’s move on from that to your 2009 work, The Long Count, an hour-long immersive multimedia experience exploring ideas of symmetry and creation. It was a multimedia song cycle commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where it premiered. How did that come about? Or what was the music? Who was the musician or the composer you worked with?

The Long Count, Title Song performed by Kelley Deal

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist

The Long Count, Bull Run performed by Kim and Kelley Deal, and Aaron and Bryce Dessner

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

The Long Count, Time to Play performed by Kim and Kelley Deal, and Aaron and Bryce Dessner

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

The Long Count, Fall performed by Shara Nova

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Matthew Ritchie: Well, I was so lucky, honestly. This was after I’d been exhibiting in galleries and Biennials, doing very much the visual artist thing. I ran into a guy at a benefit for The Kitchen, and he had a band called Clogs. I was actually a fan of Clogs [an instrumental project led by Bryce Dessner and Padma Newsome], which I thought was erroneously a Canadian band. I was like, “Oh my God, you guys come down from Toronto. This is so good.” And he’s like, “Actually, I live in Brooklyn with my brother, and his name was Bryce Dessner.” He and his brother, Aaron Dessner, were part of a band called the National, which became extremely well known for the Fake Empire [2007], which was used as a theme song for the Obama campaign. They’ve gone on from strength to strength.

And so, Bryce and I really hit it off. I think he was charmed by my complete disinterest in the National and my immense interest in Clogs, which was a classical avant-garde thing with lots of weird noises. I was like, “Yeah, okay, fine, fine the National, but tell me more about Clogs.” We became great friends. He invited me to participate in a show at The Kitchen. And as the National gathered steam, Bryce and Aaron were invited to produce something for BAM’s Next Wave Festival. Again, I think they’d never contemplated this as an option. They had already so many creative venues, so they were like, “I don’t know, do you want to write it with us and do all the other stuff?” We’ll do the music and you do the other stuff. And I thought, “That sounds cool. The other stuff sounds cool.” I’m a huge, longtime fan of Laurie Anderson and Philip Glass and all the icons of BAM, as everyone who had been in New York at that time was. It was the gold standard, the BAM Next Wave Festival. Amazing opportunity.

I had long been fascinated with the twin myth of the Mesoamerican cultures that you find replicated, especially in the Mayan. And in the K’iche’ Maya of Guatemala, and in a book called the Popol Vuh, which is their creation myth. And Bryce was a big fan of Theodore Olsen [1899-1981], who is an American poet who had been down there often. He was also very intrigued by this as a starting point, because the story is about a pair of twins, and Bryce and Aaron are identical twins. So, they said, “that sounds great. You take it away. We love that idea. If you could also make it about baseball, that would be really good, because we’re huge fans of the Cincinnati Reds, especially the 1976 and ’77 games.” They’re from Cincinnati. I was like, “Interesting.” It’s because the Mayan creation myth is all about a ball game, and these twins play a ball game essentially for the future of the universe.

As the project developed, they added, “By the way, now that we’re into this. we’re going to try and find other twins to be in the opera with us.” They invited Kim and Kelley Deal, who had a band called The Breeders, which was to be very influential. And we invited a pair of Guatemalan twins to play handball on the stage as part of the opening at BAM. Then we started to think about the antagonists in the production, who would be opposed to the twins. There is a strange, very vain, beautiful bird god, Seven Macaw, and Bryce suggested Shara Nova, an extraordinary opera trained performer, to sing two amazing parts. She played the part of Seven Macaw, who is this very vain false creator, and the Corn God. Matt Berninger, from the National played one of the Lords of Death.

The whole thing basically spiraled out of control into an almost incomprehensible variety of musical forms, as Bryce is classically trained and his brother’s very much a rock musician. It ended up being just the richest sonic tapestry of filigreed scores, opera songs, rock songs, anthems, spoken word, everything all in the mix. Incredible.

Barbara London: It feels really contemporary, and almost like sampling. You had so many things.

Matthew Ritchie: It was a banquet of sounds. All of us were like, “Well, we’re probably not going to get invited back, so we may as well just throw everything in to this.” It ended up touring around the world. Audiences loved it; we always got standing ovations. It remains a baffling moment in all of our careers, because you’ll never generate that. There was such a confluence of creative talent. Later on, Tunde Adebimpe joined and we wrote other material… We added songs, as it went along. We ended up reprising it at the ICA Boston a few years ago, when it sounded just as good.

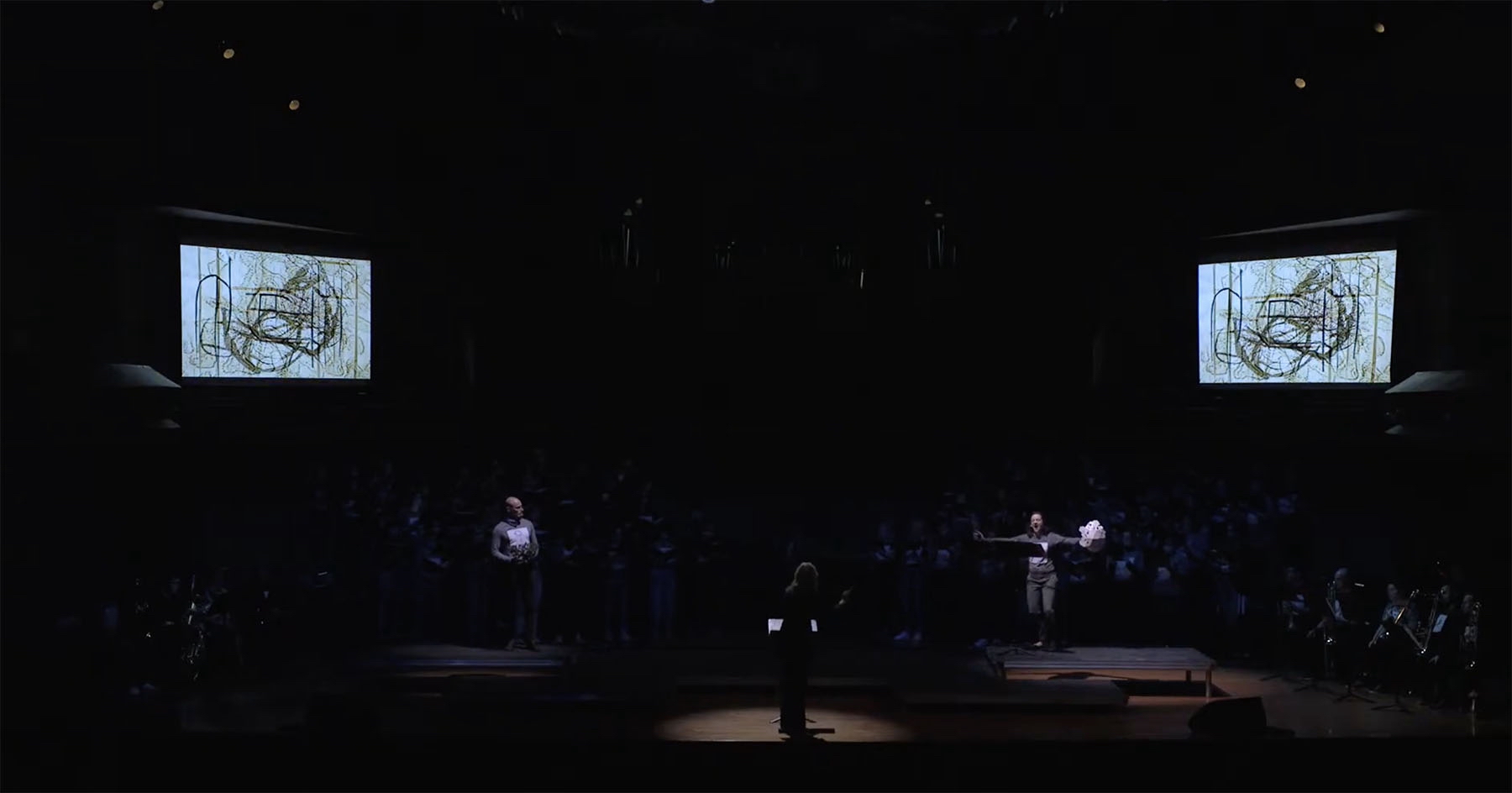

Barbara London: I think you told me there’s a link, The Long Count. Then in 2021 you collaborated with the composer and multi-instrumentalist, Shara Nova. You and Nova created Infinite Movement, commissioned by the University of North Texas. And that sounds like it was also over the top. You had an opera with two choirs, four soloists, two brass ensembles, sound design by James Eck Rippie and conducted by Kristina MacMullen. Also, over the top. It fuses artificial intelligence with the story of Paradise Lost, the epic poem written by John Milton (1608–1674). You’ve engaged in some pretty wild endeavors.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Matthew Ritchie: Yeah. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that a lot of this was tied into a project called The Morning Line (2008), which was a touring musical with mutable structures, that I worked on with Bryce Desner and a number of other musicians, including Evan Ziporyn. It toured all around Europe, and in each country, we would add more recorded compositions. I think it was a model of the universe that you could walk inside with a soundscape. I think that inspired me essentially to think about music as having no limits so that by the time we got to the project at the University of North Texas, which is another one of those beautiful connections with Shara, I was like, “I just love doing this.” I love it when you can just throw caution to the winds.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

And there we were incredibly lucky. The university invited me to do a public art piece. Then COVID happened, and they were like, “We had a lot of extra time.” Then they said, “Why don’t you do a residency, an online residency?” I thought, “Well, University of North Texas has the second-biggest music department in America.” I was like, “Can we work with them?”

I found a professor there, Dr. Kristina MacMullen, and contacted her. I asked, “I’m thinking of this Shara Nova who went to UNT as a collaborator.” And she says, “Oh my God, Shara Nova; I sing my children to sleep with her songs every night.” They have a enormous 100 person choir, so we were able to stretch out in ways that were absolutely impossible. And Shara seized the opportunity, “Well, when I was there, I don’t think people took me particularly seriously as a composer, so I’m going to show them what is what.” She wrote twenty songs in twenty different song styles from medieval choral to super operatic, high coloratura to ambient Meredith Monk-style pieces and very much all in her own idiom, which is absolutely brilliant.

Again, I was fortunate in my collaborator. I tend to work with them in a very open way. I provide them with a text that allows them the maximum flexibility, which they happily explore… I’m like, “Throw away as much as you want.” It’s not about framing this. And then we’ll work through it and find out. And that seems to work out really well. I give them a whole pile of stuff, and then they throw most of it away. It creates a very positive relationship because I don’t really have a proprietary feeling about the logic of the text; it’s really about creating this ambient soundscape.

Barbara London: I want to go on to something that very much reflects your visuals and very much touches on science, we could say. So let’s move on to your work from 2022, A Garden in the Machine, which premiered at the James Cohen Gallery in Tribeca. I remember thinking that the paintings had all your signature elements: earthy color, visceral shapes, mysterious lyricism combined with theory. For the work, you collaborated with Sarah Schwettmann, an MIT scientist you have collaborated with since 2018 on cross disciplinary projects that explore a type of machine learning known as Generative Adversarial Networks, GANs. These treat images as data from which to develop new imagery. In essence, this machine learning is a serialist image generator from which you built the compositions in this exhibition. They were very beautiful but very, very complicated. What was it about machine learning that interested you? Also, what’s the meaning of the title, A Garden in the Machine?

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Matthew Ritchie: A Garden in the Machine was an effort really to create an exhibition out of something that’s quite a vexing subject, which is artificial intelligence and, what can we say, its effects? Its omnipresence, its secret malign agenda. It’s a very complicated way of talking about something quite simple, which is a long-term human project. We’ve been trying to make something like artificial intelligence for thousands of years. We have myths about it going back to Galatea [the Greek myth]. For some odd reason, we’re interested in the idea of a created intelligence. And we’re getting closer. It’s ominously close.

When I first saw the GANs, that Generative Adversarial Intelligence up at MIT, it was at something called a hackathon, which was a strange event between the Metropolitan Museum, Microsoft, and MIT, which had collaborated to allow researchers to look at what a supercomputer could do with adversarial networks. Microsoft was allowing us to use something called Azure. I was an artist in residence then, at the Center for Art Science and Technology.

I instantly thought, well, this is new, for the first time I could see what computers thinking looked like, rather than lines of code. You see in the matrix, computers thinking is always represented as ones and zeros. It’s absolutely uncanny to see ones and zeros turn into pictures in real time. Cross the uncanny valley over into something very close to what a lot of my students would make in the studio, as a sketch of an artwork.

That tradition you mentioned, of surrealism and the automatic image generation, is also something musicians and poets use a lot. David Bowie was a famous user of one of the earliest automatic computerized text generators, something I was familiar with from the world of music and from the world of art where you hybridize things and create beautiful corpses out of these weird combinations. But the eerie thing about artificial intelligence, in the form of machine learning, is it is automatic. It doesn’t really require human input. And it contains within itself all of the possible variations. It doesn’t just make one. The mathematics of it is, what’s called latent space. And in the latent spaces of any given program are all of the possible variations that could come out of that space. You’re not just seeing a drawing that a computer has made with a bunch of random inputs, what you’re seeing is just the very, very tip of the potentials that it could generate.

Happily, I was encountering this early enough that you could really see the gaps where it was messing up. There are these beautiful blobs, really, where the computer couldn’t identify enough information so it produced these strange circles and glitches. But I saw in it a real affinity to something that precedes what you might think of as canonical western art going back to England and the “insular tradition”, which are these versions of the creation and the apocalypse that were produced off to the side, where they really did not know how to make pictures in the sense that we think of them.

I’m specifically talking about 800 AD, when some monks in Ireland created the Book of Kells. One page is a gigantic doodle of two letters, that probably took years of one guy’s life. And it’s amazing. It’s not really based on anything. It’s not based on the text. There’s just this ornamentation and elaboration; this filigree gets produced almost to fill in the gaps. And you really sense that with the AI of machine learning. Whenever it can’t fill in the gaps, it will just add a layer of information that it hopes might be relevant. But if it isn’t, it’s interesting anyway. I felt in that you’re in the presence then of a fullness that is also empty, or an emptiness that is also full. And it’s very disturbing and also fascinating, because the quality that surrealist art has of a slightly decadent quality where it’s like a Max Ernst painting, for example Europe after the Rain (1940-42), where there’s just a little too much muchness. It’s a little bit like a sci-fi book jacket. He is just going for it.

And you can’t really have a decadent machine, but there’s a decadence to AI in that it’s vapid and yet overproduces. There’s just an endless amount of it. And the endlessness is a machinic quality that reminds me of the kind of mindlessness of vegetation when you have a giant willow tree growing out of a stream, or brambles, and they are just way too much. They have been given way too much resources. And it’s actually a monoculture. It’s not really doing anything good for the landscape, it’s just a weed, but it’s grown to the size of an enormous tree. And now you’ve got this thing, and you’re like, “Wow, it’s beautiful and hideous at the same time.” But if you just let it go, it’s just going to engulf everything else with this monoculture, so you’ve got to be very conscientious about one’s appreciation.

It is now a fully functional part of our society. It’s co-creating our cultural information. So, to disregard it, or to pretend it’s not happening, or just say it’s very bad and we should stop it, these are all legitimate points of view, but they’re not realistic. It’s not going to be stopped. It is going to take a lot of jobs away. It’s going to use up huge amounts of energy for no reason, much like many invasive species like the lantern fly or something. Here it comes.

Barbara London: I like these analogies.

Matthew Ritchie: I thought of a garden, both because it is a complicated term and because it related to the project Infinite Movement, where I had two characters: one called the Generator and one called the Discriminator, who are the components of the adversarial network. They argue with each other about the nature of creation and the universe. This was the early days of ChatGPT. One is afraid. The Discriminator is always trying to control the universe, and the Generator always just wants to make more. The generative adversarial system has built into it this odd schizophrenia.

Barbara London: Definitely in this work, A Garden in the Flood, there were paintings, weren’t there? There were beautiful paintings on the wall. It operated on many levels, right?

Generator

Oil and Ink on Canvas

2022

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Photo: P.d. Heurle

Discriminator

Oil and Ink on Canvas

2022

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Photo: P.d. Heurle

Matthew Ritchie: Yeah, in the sense that drawing pulls it all together. In the Infinite Movement opera, there’s an adaptation of Paul Klee’s notebook where this extraordinary beautiful singer, a counter tenor by the name of Daniel Bubeck, who’s playing a character, the Discriminator. And the quote is, “The first case, the active line.” Paul Klee had this wonderful idea of a line goes on a walk, and out of that comes drawing, painting, singing, the universe. So the Discriminator is describing the initial condition of the universe as a line that goes on a walk.

And if one wants to be poetic, you can imagine that the wave forms that constitute the fundamental structures of string theory or the loop gravity are lines or waves that are, in a sense, drawing everything together at the same time. You can see the universe as an oscillation. And in the exhibition, A Garden in the Flood, we placed Telmun, which was the film that accompanied the song, A Garden in the Flood, in the middle of nine other films that I’ve made including elements of The Long Count.

And together, they form a giant hyper project called The Arguments that I’ve been working on for fifteen years, which is a title I borrowed from the original subtitle of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, where each book is presented as an Argument. There are actually twelve in the final version, and I’m up to ten. I’m just working on number eleven. There’s one more to go after that. Collectively, it’s about eight hours long, eight hours of music. It is set inside this filigreed map that has all these almost stained-glass windows. Each one of which is a film, an animated film, used with very different kinds of machine technology. Some are based on video games, Machinima, artificial intelligence. There’s a whole variety, really, reflecting the time span of the piece.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

I love this idea that when we draw or make art or sing songs or write books, we’re making arguments for creativity, for new worlds, for better ideas. We’re doing something bigger than ourselves. And we’re not just arguing for the sake of it or for power, we’re presenting a vision. And when that first line, “Went on a walk,” whenever that was billions of years ago, it started the argument. But the argument was always about making more and making it better and more beautiful. It was never about cutting it up into smaller pieces and making it less.

Barbara London: Let’s have more.

Matthew Ritchie: More, always more.

Barbara London: Did you carry over those ideas into the work I saw last year in Nashville? I was very fortunate to see A Garden in the Flood (2022), which filled the second floor of the Frist Art Museum. It was an outstanding collaboration of yours with the Composer Hanna Benn and the truly remarkable Fisk Jubilee Singers, vocal artists based at the Fisk University in Nashville. It’s the Frist Museum and the Fisk University. I want to go back to 1871, which is when the original Fisk Jubilee Singers introduced so-called slave songs to the world. And they were instrumental in preserving this unique American musical tradition known today as the Negro spiritual. How did that collaboration with the Jubilee Singers come about? He sadly passed away, but did you work with the great Paul Kwami?

Ten-channel multimedia installation with sound database, acrylic, and ink.

Courtesy of the James Cohan Gallery and the artist.

Matthew Ritchie: Yeah, it was an extraordinary loss. He wasn’t just a great teacher, but a mentor and a pastor and a thought leader for his entire community. I was incredibly lucky to work with someone like that. It’s like meeting a truly, I would say, a genius in the old sense of the word, a genius of a place, a genius loci [the protective spirit of a place]. He informed the tradition and re-informed it.

If you go back and listen to the Fisk Jubilee Singers, they have had many iterations since they were formed. Dr. Kwami was from Ghana originally, then came over, went to Fisk and brought with him an awareness of that tradition exported from West Africa, the forms of the songs and the manner of singing. It was a journey of endurance and the triumph of hope over experience, in a way.

He was far too polite to say it when we first met, but he said to me afterwards, “I wondered what has the Lord brought me now?” It is a big swing for an old white British guy like me, whose background is the 1980s, to show up Nashville in his home territory, in the chapel at Fisk University and say, “Oh, I think it’d be great if we could collaborate.”

But what I brought with me was a story of my own from the western isles of Scotland, where a tradition called” precenting the line” is still carried out today. It’s a very original form of singing. It’s where a precentor (or a presenter) sings out and the congregation sings back in whatever ragged form they can. It was actually banned, the practice of it in England in the 18th century, as ‘the old music’ when ”shape music” replaced it. And this tradition intersects with the story of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. There’s a beautiful documentary about this produced by Dr Willy Ruff, a Yale professor, called A Conjoining of Ancient Song that describes how line singing was brought over by the displaced persons from Scotland when they were cleared out in the clearances, and who then became indentured workers in the fields in Tennessee working next to the enslaved persons. They would have been the next social level up, nominally free, but still working for the overseers, still working for the landlord. One can only speculate because there is obviously no Ted Talk or YouTube from that time about this, but Tennessee was famous for its independent churches and the styles of singing that were maintained. And the documentary draws attention to the likelihood that what we call the “sorrow songs”, built around call and response, essentially the foundational elements of modern music came out of the fields of Tennessee, from these songs being sung and the white churches and the Black churches being right next to each other. After the Civil War, when the Fisk Jubilee Singers, composed largely of freed persons, were on tour, that was the first time anyone had seen Black people singing in white spaces. Not only were these songs never heard before, but people had only ever seen minstrel shows. but that was a bumpy ride. It took them a couple of decades. Eventually they became an international phenomenon. They ended up in London in the court of Queen Victoria, who was too old and probably too rich to care where they were from, so just said, “Oh, we greet the people from Music City,” which is how Nashville got its name, not the Grand Ole Opry.

So, when I went to Dr. Kwami, I was really saying, “I want to do a collaboration with the most authentic source of music in Nashville. This is where Music City comes from. It’s where it got its name. It didn’t get it from Country Hall Music Hall of Fame, it got it from you guys.” I think at that moment we found a common bond. And later, I was reminded by a friend of mine that this was something that Paul Gilroy, who I mentioned at the beginning, had written about in ‘The Black Atlantic’. It was literally the diasporic journey of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and how this is one way to think about an alternate history of globalization: through the history of music and how central the Fisk Jubilee Singers were to that.

And then, I was lucky enough, as you said, to work with Hanna Benn, who was recommended by Shara Nova, who produced an absolutely extraordinary new gospel song, the first new gospel song they’d recorded in decades. And watching Dr. Kwami work with the singers, each word of it, he would say, “What does this mean? What does it really mean to pull into being the struggle?” The theme of the song is really a counterpart to The Garden in the Machine. It is, in a sense, that the much older tradition of the garden is what we preserve in the face of the flood. It is what we truly value and what is of value. It is the Garden of Eden, but also the garden of what we think of as culture in the face of the flood, of an endless machinic and mass-produced world. What are we really gardening? Ourselves, our culture. How much care we must lavish that to allow that to survive. I think that really resonated. And I would also say it was an absolute highlight of my entire career as an artist working with him. Making this piece happen was just a joy.

Barbara London: I think that’s a beautiful way to conclude. And I feel very fortunate that I was in Nashville to see it. I want to thank you so much.

Matthew Ritchie: Thank you.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Ryan Leahey, with audio engineer Amar Ibrahim and production assistant Sharifa Moore.

Support for Barbara London Calling 3.0 is generously provided by the Richard Massey Foundation and by an anonymous donor.

Special thanks to Masayoshi Fujita and Erased Tapes Music for graciously providing our music.

Thanks to Independent Curators International for their help with the series. Be sure to like and subscribe to the podcast so you can keep up to date with new episodes in the series. Follow us on Instagram at @barbara_london_calling.

Web design by Sol Skelton and Vivian Selbo

This conversation was recorded December 13, 2024; it has been edited for length and clarity.