Barbara London: My guests today are Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, two sound and installation artists who began collaborating in 1995. Based in rural British Columbia, they often travel internationally to develop and install their artwork, which explores the idea of narration and the plasticity of noise, sound, music, and poetry. Their work has been shown in many exhibitions and in major museums around the world. Janet and George, thank you both for joining me.

Janet Cardiff: Oh, thank you for inviting us.

George Bures Miller: Yeah, it’s great to be here.

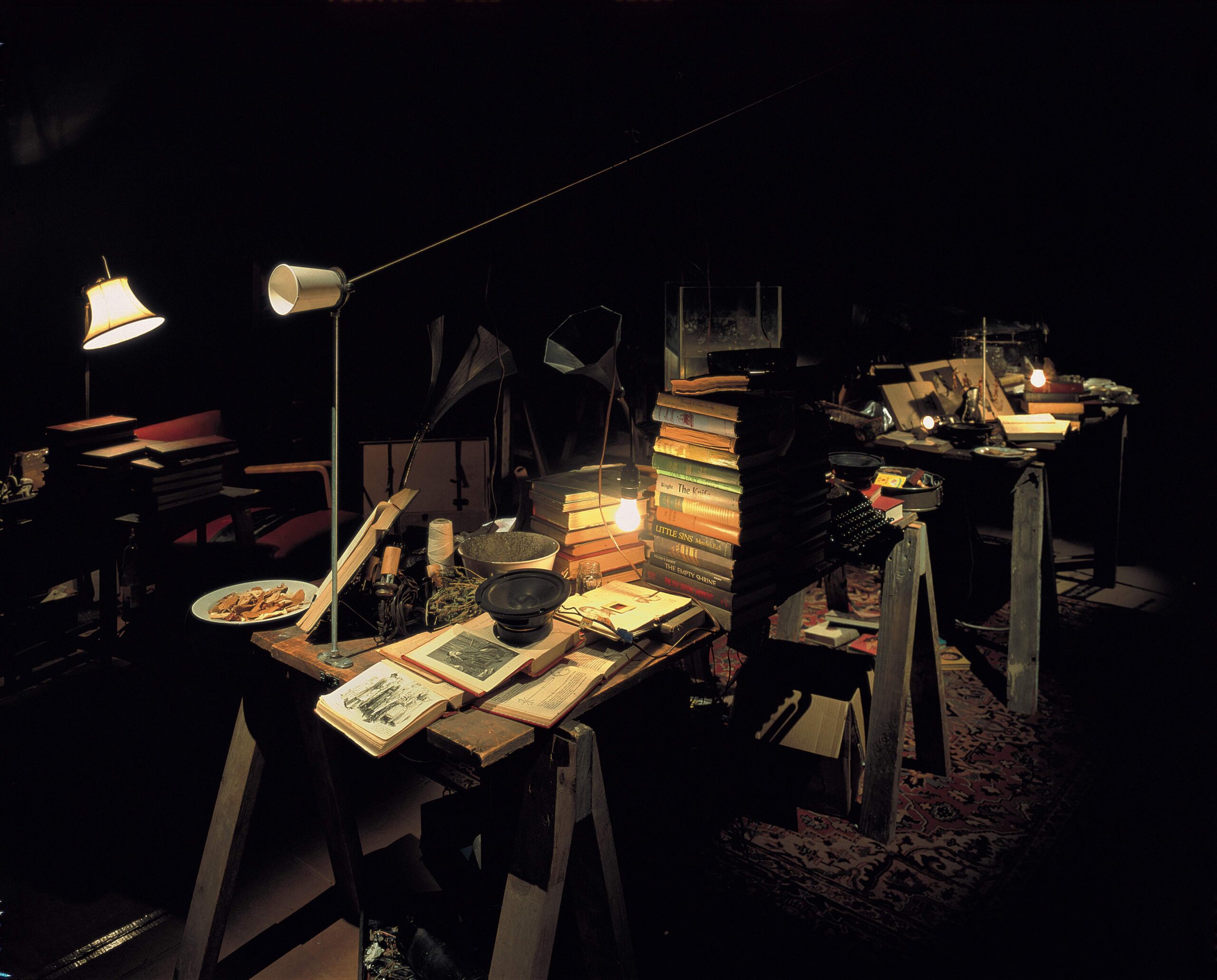

Barbara London: Although visual, to me your work is sonic at its core. So, let’s begin with your first collaboration, The Dark Pool (1995).

The Dark Pool, 1995

Mixed media, audio installation

Dimensions approximately 10 x 7 meters

Voices: Audrey Baster, Lise Gibbons, Caitlin Murray, Amanda Murray, Michael Turner, Judy Radul Photo Element: Vaughn Berg.

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York.

Photo: Paolo Pellion.

On entering the installation, the audience encounters an elaborate assemblage of furniture, carpets, books, empty dishes and mechanical paraphernalia, a realm of suspended animation. Moving through the installation, the audience activates acoustic components of the work: strands of music, echoes of stories, and fragments of dialogue. Similar to your other work, the viewer engages with a magical environment, almost a cabinet of curiosities that has a strong sense of personal history. Can you tell me about how this first collaboration came about?

Janet Cardiff: It was 1994, when I was invited to do a residency and show at Western Front in Vancouver and I didn’t know quite what we were doing or what I was doing. George and I had lived together for a long time, and we would sit and have coffee together, talk about ideas a lot and stuff like that. We had this one piece that we couldn’t remember whose idea it was. So, I proposed to Western Front, the space in Vancouver, “Could we possibly do a collaboration for this piece?” They went, “Sure.” So basically, it was the first time that we officially worked together.

Normally, I would help him out with his work, and he would help me with my work. I would be doing the camera on his work or something, and he’d be helping record on mine or help with printmaking or whatever we were doing. So, it was nice to be able to collaborate. It was great fun.

George Bures Miller: It was a bit weird, because at first, we couldn’t figure out who was boss. We both always worked on each other’s work a lot. I’d ask Janet, Well, what did she think of this? But in the end, I would be the one saying, “Well, yeah, I don’t like your idea. This is better.” But then when we started working on The Dark Pool, it was like all of a sudden, we had to always be thinking about, “Oh, so now I have to take her opinion into account.” It was a nice shift in a way, but it took some adjustment because of that.

Janet Cardiff: In terms of the sonic quality of that piece, we first started working with sound back in the 1980s actually. George went to the Ontario College of Art and Design, and all of a sudden, he had access to a sound lab. I was the mooch student. I would go in at nights and be able to play around with the equipment. I discovered when I started working with sound that it was almost like coming home. It just felt so natural for me for a medium, because I’d been trying to work with narrative in my printmaking, as well as in some of my little sculptures and things like that. I’ve always been basically based in narrative, and sound has this quality — it deals with memory, it deals with time. So, you can take people along and say, “They can still remember what they heard thirty seconds before, and they are expecting something in the future.” It’s the way music works, right? Because a musician plans it so you know the note that’s going to be the next note, and you can remember a few bars back. But then before that, it melds in your memory. I love that, how you can have almost this peripheral memory as you’re listening to something, and that can influence your current listening ability. I felt really comfortable in sound, once I started working in it.

George Bures Miller: We loved it also because it bypasses your intellect and gets straight to your emotions. It just goes right inside of you. You can’t close your ears. Well, you can close your ears, but it’s difficult. Even if you do close your ears, a bass drum will go right through your whole body. It’ll ring through your bones, and you’ll feel it in your stomach. There’s something that is just so amazing about how sound can affect us emotionally. So that’s why we love it.

To Touch, 1993

Wooden carpenter’s table, electronic photo cells, 16 audio speakers

Dimensions: Table: 98cm x 140cm, room size variable

© Janet Cardiff; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

Furthermore, about Dark Pool, it was a continuation of some of Janet’s early sound installations where we use multi-speakers. In one, called To Touch (1993), there’s an old table. You move your hands over it, and it triggers sounds. So, in Dark Pool, the sounds are triggered as you walk through the piece, but we added a lot more little sculptures and old furniture. We really like using inanimate objects or old things, old objects like telephones or old speakers. They have an inherent storytelling ability. People see them, and it triggers something for everybody. Every object may be different for everybody, but something comes up about it.

Janet Cardiff: Yeah, because it’s the same way with sound and object, in that you are referencing. If you have, say, an old toaster, well, someone comes in, and they see that toaster and go, “Oh, my grandma had one just like that.” They’re able to access their own memories, and then add that as a layering element to our narratives. That’s why I think we work in narrative in that abstract way. We really want the viewer to bring a lot to it. We found that certain vintage objects, because they have been around so much, have a certain sense of theatrical-ness. But they also have a sense of memory and texture, and all that leads to reminiscing.

Barbara London: The objects have a patina. But to me, that aspect of your work makes me think so much of the world of dreams and fairy tales. I think what you do with that memory — you evoke really a sense of wonder in the audience. Do you think that’s true?

George Bures Miller: I think we definitely try to do that. Our most successful pieces do that. They give people that sense of wonder or transport people away from their everyday life. Janet’s Walks do that literally — take people away from their whole life. You take over their sound listening and you take them on a tour of a city. People who have lived in the cities that she does her Walks in, they go: “I’ve never seen any of this city before. It’s a whole other kind of thing.” So that transportation is quite effective in the “Walks.”

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller

Alter Bahnhof, 2012

Video walk

Duration: 26 minutes

Commissioner:

Produced for dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel, Germany.

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy of the artists

Janet Cardiff: It makes me think about this concept of “wonder “you were saying. The Walks, I think, create this three-dimensional sound that is layered with a physical world, so people are placed into a virtual space mentally. But I’ve often thought about wonder and beauty, and why is it that? Is it part of our ancient genealogy? So that when we look at the stars, it makes us wonder and we go, “What are these things?” It makes us curious, and it makes us appreciate the world.

George and I lament sometimes that there’s not enough wonder in the world. So, in one of the current pieces we’re working on now, I’m really thinking about this idea of magic and wonder. How do you take people past the intellect and just make them create undefined narratives?

George Bures Miller: We really love dance choreography and people like Pina Bausch. I think she works in a similar way; or we have been influenced to work in the way that she might work, by just giving you a snapshot of a scene. Maybe there’s not even any movement or dance in it. It’s just gives you a sense of a snapshot of reality from somewhere. It gives you a mood. It gives you an emotion. You get all kinds of things from it, but you can’t put your finger on what it is.

Janet Cardiff: But about the dreams, I think because over the years and decades I have done a lot of recording of my dreams. I think the surrealist juxtaposition is one of the things that interests us. That came across a lot in the Walks. So perhaps some of the audio narratives are structured in such a way as a similar structure of the content of our dreams.

George Bures Miller: It’s funny. With our work, we always say what we want to do to each other. We’re talking about it, but in the end, sometimes they don’t work, or they’re not doing what we want them to do. So, we go back, and we work into them really quite vigorously, changing them up and taking out parts, trying to get them to do what we want them to do.

Barbara London: Well, I think of your work and you as artists, and hearing you say those words, it’s like you really pay attention, and you deal almost painstakingly with attention to detail. Your installations are that way. You’ve worked them. You think about them. You choose the objects. I find them quite extraordinary.

George Bures Miller: Thank you. I’m glad that you say that because, I mean, we do. It’s a painstaking process, but I don’t think most of our audience realizes it.

Janet Cardiff: I think it’s like slow cooking rather than fast food. I mean, we do labor over it, but because of our personalities being so different and working together, it creates a different working process.

Barbara London: I’ve experienced quite a few of the Walks, including the one you did for SFMOMA. I went into storage places, weird hallways that the public is never allowed into. Being a museum person, I understood exactly what that was and what it meant to the museum. You did one in Kassel, Germany, and in many different cities, including New York’s Central Park and Münster. The listener has on a Walkman and they hear Janet whispering in their ear, making them pay attention. They’re fascinating. Tell me something about those.

Her Long Black Hair, 2004

Audio Walk with photographs, 46 minutes

Curated by Tom Eccles for the Public Art Fund, Central Park, New York

© Janet Cardiff; Courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Public Art Fund, New York.

Münster Walk, 1997

Audio walk with mixed media props

Duration: 17 minutes

Commissioner: Curated by Kasper König (with assistant curator Ulrike Groos) for Skulptur

© Janet Cardiff; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

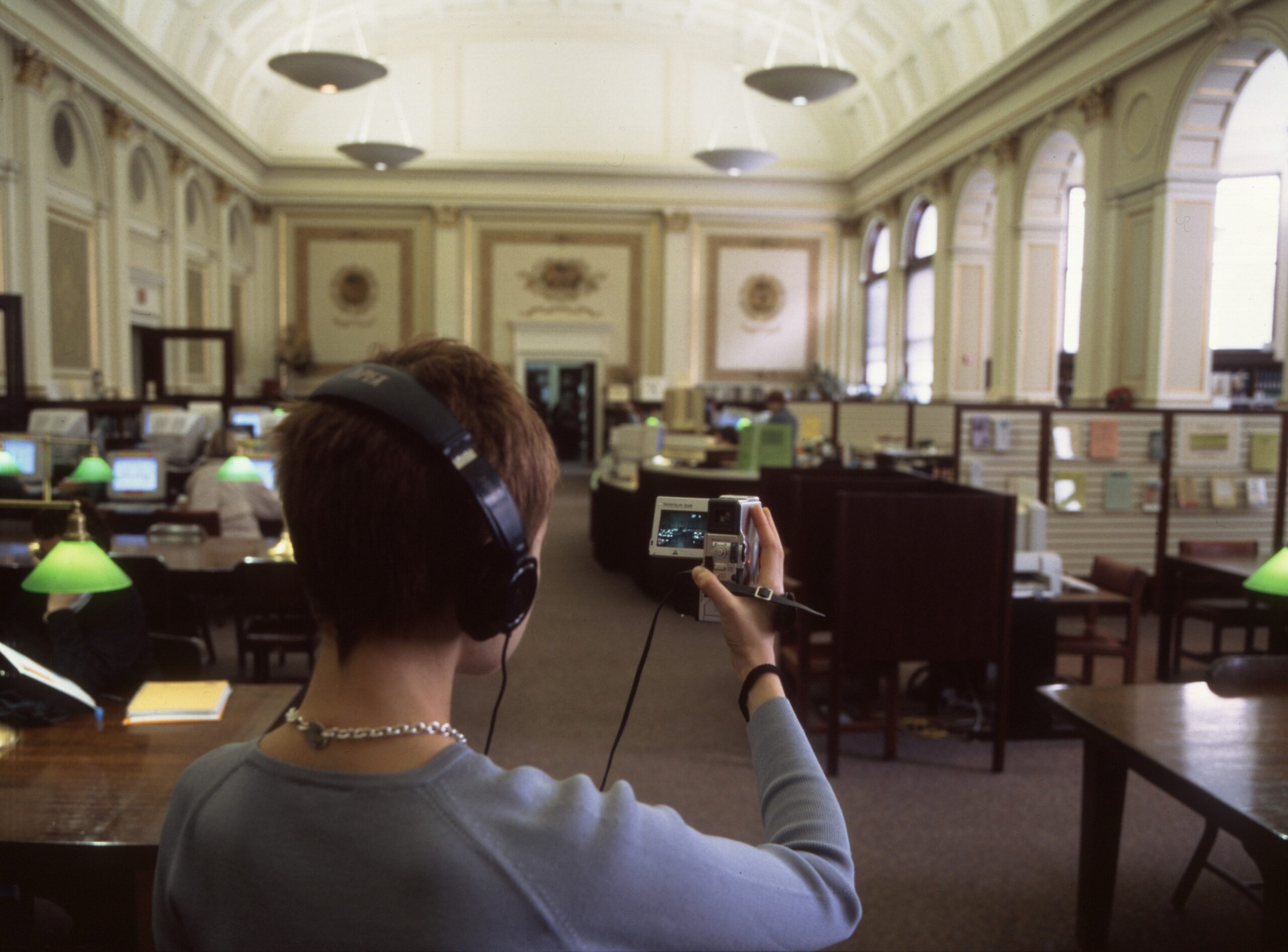

George Bures Miller: Well, first, for someone who has never done a Walk, they started in the old days. It was a Walkman, a cassette recorder, and a pair of headphones. You’ve been given them, then you’re told to follow the instructions that Janet’s going to give you. You might be walking in a museum, you might be walking in the streets of a city like Münster in Germany, and you just give yourself up to this strange woman telling you where to go and what to do. Then strange sound effects happen.

What’s really interesting about the Walks is they’re recorded using a technique called binaural audio. So, played back on headphones, they give you a hyper-realistic effect. You’re not sure that what you’re hearing isn’t actually real, especially when they’re recorded in the same location. So, you’re walking through the streets of Münster, and you hear the chapel bell going off, but the chapel bell could be on the headphones or it could be real. You can’t really differentiate it. So, there is a whole confusion of the senses that takes place right away with one of the Walks.

Janet Cardiff: I’ll tell you how it started. I was doing a residency at the Banff Center in Banff, Alberta. I was recording what I was seeing in front of me, then I pushed the wrong button and replayed it and heard my voice describing what was in front of me. That simple thing just created this serendipitous situation where I went: “This is interesting. I do not know why it is interesting, but it’s interesting.”

I learned later, after years of doing Walks and doing some research, that people see more when you describe what they are seeing. I think partially, the Walks are like that. But also, like George was saying, you’re in a virtual world but also a physical one. I think there were other artists that had been working in “walks”, but I think what we contributed was this idea of physical cinema. They were always script-based and narrative-based. Then we’d play out and we’d have all sorts of people making sound effects for us — people running by, people screaming, bombs going off. The London Walk had sound effects from the Second World War and it had all sorts of things. But then, at the same time, it changes over time. We were there producing it in Brick Lane, in London, and there was a guy bombing different places. One day, I was out recording and a bomb went off on the same street I was recording on, ten minutes after I walked past the store. So those sorts of things come back, and if they’re replayed on the same site, they are unique for every different person.

People also have a different focus. They have a different attention span, and they also have a different way of listening, and because they’ve been changed by smartphones and by listening to music and AirPods and everything like that. It’s very interesting how technology in our society changes how people experience art.

George Bures Miller: There is also the video Walks. We started with Janet’s audio Walks, then one day, Janet was sitting on the couch with a video camera that we had just purchased, and was shooting me, filming me. Then I left the room, and she did the same thing: She replayed the video back, then she realized, “Oh, I’m looking at George on the couch, but the couch is empty. This is really interesting.” It’s another one of those aha moments.

We had been working on these pieces called Robotic Telescopes that actually had a recording inside of them and they would move. It was like, “Oh, the person, the audience, could become the robot and follow the motion of the camera.” Then we started doing these things called Video Walks. They were quite expensive at first, so we had to have curators willing to spend a lot of money because the little video cameras cost a thousand bucks each, and if you wanted to have 18 or 20 of them…. I think the first one [In Real Time, 1999] was for the 53rd Carnegie International.

In Real Time, 1999

Video walk

Duration: 18 minutes

Commissioner: Curated by Madeleine Grynsztejn for the 53rd Carnegie International at Carnegie Library.

© Janet Cardiff; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

Janet Cardiff: The 53rd Carnegie International was curated by Madeleine Grynsztejn.

George Bures Miller: Exactly. What was weird about that was then, all of a sudden, we realized how strong our sense of vision is because even though the screen is only two and a half inches, people were just drawn right into that screen and they didn’t look around anymore. Even though we still recorded binaural audio, they barely noticed the audio. With an audio walk, your senses are opened up. It felt like people would come out of it and go like, “Oh, I’m seeing everything and everything’s big and beautiful.” In a video walk, people would come out, and they’d be like, “I feel like I was just on some kind of acid trip.” It’s like you close down in a way.

Janet Cardiff: So, after doing several video walks, we work with the structure, so that we turn off the video sometimes, so people all of a sudden are in the aural world.

Barbara London: Let’s move on to Museum Tinguely and what interests you about him. I find that Jean Tinguely was a fascinating artist, and not everybody fully understands his take on technology.

George Bures Miller: Well, I first saw Tinguely’s work in a magazine called Horizon. It was a hardcover magazine that, I’m not sure why my parents even subscribed to. I lived in a small town in the middle of Western Canada, and they had this magazine. I saw his work in it when I was nine years old and I just was completely fascinated. I loved the playfulness of it, but also the darkness of it. You could see, even though these were stills of moving pieces, though the photographer shot them so they had blurs and everything. You could see that it was moving, and it was just amazing to me. I don’t know. When I went to art school, interest fell by the wayside because Tinguely went out of fashion for quite a while.

Janet Cardiff: I think also it is through the movement. That’s the key issue, and we’ve used that a lot in our art, because as soon as you make something move, you’re of course bringing it to life. It’s like as a kid, you’re playing with little animals. You move them around, and you try to animate them. Also, time has always been a big issue. Because of the nature of audio, of course, time comes through. But it’s always curious to work with movement in that sort of way; what do you expect next? It’s going to move here, but then this is going to move, and then this is going to move.

George Bures Miller: Tinguely’s pieces became performative, right?

Janet Cardiff: Yeah, totally.

George Bures Miller: I mean, they were performative even to the point of his Homage to New York [1960] becoming this incredible performance, where he burned up or blew up his machines.

Janet Cardiff: That’s a great piece I love.

George Bures Miller: That’s an amazing piece.

Janet Cardiff: Also, he was always working with found objects. We really appreciated that. For example, there was some factory that went out of business, and he got all the wheels for the work. Ironically, one of our main assistants was Carlo Crovato. Because of his experience in Basel, where they saw how he could fix things and whatever, they invited him to be an assistant technician to set up a new Tinguely show that’s on right now somewhere.

George Bures Miller: He spent a month in Italy setting up Tinguely’s work every day.

Janet Cardiff: Also, we found people to work for us that had abilities to work with motors, and make things move.

George Bures Miller: Because of our interest in his work, it was such an honor to be asked to show in The Tinguely Museum, even though I am probably sure he would be peeved off, but it was very amazing. What I really liked about doing the show was that every morning and evening, we could walk through the galleries of where his work was permanently installed. I got to see so much stuff that I’d never realized he’d done, like the experiments and different things. He created a gamut of work that we don’t really know about.

Usually, you get your art history with a couple of different types of machines, but he did so many different things. He was so prolific, making so much work. I love the radio pieces where he had these motors tuning the radios in and out.

Janet Cardiff: Yeah, that’s fantastic.

George Bures Miller: Three or four of them, just making the sound work out of the airwaves. Incredible stuff.

The Forty Part Motet (A reworking of “Spem in Alium” by Thomas Tallis 1556), 2001

Installation view Johanniterkirche, Feldkirch, 2005

Duration: 14 min. loop with 11 min. of music and 3 min. of intermission

© Janet Cardiff; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York. Photo: Markus Tretter

Sung by Salisbury Cathedral Choir

Recording and Postproduction by SoundMoves

Edited by George Bures Miller

Produced by Field Art Projects

The Forty Part Motet by Janet Cardiff was originally produced by Field Art Projects with the Arts Council of England, Canada House, the Salisbury Festival and Salisbury Cathedral Choir, BALTIC Gateshead, The New Art Gallery Walsall, and the NOW Festival Nottingham.

Barbara London: Let’s move on to a work of yours that was part of that retrospective, and that’s your Forty Part Motet from 2001. I’ll give the little backstory. Then you can say a lot. The installation is based upon Spem in Alium. Spem in Alium is a choral work from around 1570 by Thomas Tallis; his work was composed for eight choirs of five voices each. So, upon entering Forty Part Motet, the visitor encounters forty loudspeakers, each about the size of a human head. The speakers are mounted on an individual metal stand, and arranged in a large oval.

Each speaker portrays an individual singer, and the whole circle simulates a virtual choir where the movement of the voices around the space creates an almost physical sculptural experience. The visitor might stand in the middle of the oval and listen, or walk up to a speaker and connect with that voice of someone singing a part from the composition. So, visitors individually deconstruct or reconstruct the composition by their movement around the room. The work is fourteen minutes, and it is really quite magical, and even quite healing. The work is in MoMA’s collection; every time it was on view, people were just stuck to the room. What led you to create Forty Part Motet?

Janet Cardiff: I was working on an audio walk in London commissioned by British Airways. I was hiring this singer, who is an opera singer, and had her move around. Because I’m recording with the binaural audio, she recognized that I really love the three-dimensional, sculptural aspect of music. So, the next day, she brought me a CD that had Spem in Alium on it by Thomas Tallis. Thomas Tallis is a very famous British composer. He’s written so many brilliant pieces of music, but this particular one is one of the most famous and most complex pieces of choral music ever written, having forty different harmonies.

So, when I brought the CD home to a little town in Alberta, and eventually put it on the CD player, immediately I went, “Oh, I just want to get inside this music. I want to hear it.” I could see it in my mind coming from all over the place, and just imagining what it would be like. So, George and I were sitting in our living room and listening, and I said, “George, we have to do this piece. It’ll be easy. We just have forty CD players, and record forty singers.” Then George laughed and went, “No way. This is incredible. This is a lot of work. There’s no way we can do it with a technology that exists at this time.”

George Bures Miller: I was the big skeptic. I had all these concerns, “Well, it’s going to cost this much to do this.” Also, we’d just been asked to do the Canadian Pavilion for Venice Biennale as a team.

So, we were already working on our project for that, and that was the big project. Janet was like, “No, we got to do this for something else.” I was like, “Well, you’re going to have to find a system like a forty-track playback system that we can afford to put in a gallery.” There were no computers at that time that could do that. Then I was like, “Even to record it, we’re going to have to hire a truck with a huge studio inside of it, and then we’re going to have to find a choir.” So, I was all negative about everything. Then Janet was like, “Yeah, but it’s going to be great.”

Janet Cardiff: It was a producer in England, Teresa Byrne, that approached me. She basically produced it; she found the singers, and found I wanted to work with children, because I love the children’s voices for sopranos. We had to spend $100,000 on it. When we heard it that first time in Ottawa, it wasn’t quite working like I wanted. Because after you see the score, you see how the music moves. I wanted the installation to have movement around the room. Speaking of Tinguely, it’s the same kind of thing. It’s this idea of movement and how then that triggers people to move, as well.

After that George edited some more, so that took out crosstalk and different things, and finally got it working, I felt it worked. When it works in a space, you just feel tingles. I think partially that is because the frequencies of sound go right into our body. The whole world exists on frequencies, frequencies we can’t hear, because they’re too low or too high, but we’re still affected by it. Now, they’re working a lot in sound therapy, and on how much sound can affect the body, and can affect our whole sympathetic system so that it can create tension, or it can create relief.

George Bures Miller: That’s why the piece is healing.

Janet Cardiff: I think Thomas Tallis naturally knew this. It is composed for probably a chapel with high ceilings, referencing this idea of angels singing. It starts with choir one, and it moves around the space. But a really unique thing about the piece, too, was that on bar forty, there’s forty singers, they’re all singing at once. So, it’s this crescendo of voices that just gets right into your body, all this beautiful sound hitting you from all over the place. Then it goes backwards in the choir. So, then it goes from choir eight down to seven, six, and then all this, and then back and forth.

I always feel like it’s water. It is back and forth like water, moving like water. I think I was so thrilled to be able to work with this piece of music. But over the years we’ve discovered that it doesn’t work in every space. First of all, we always have to tune it for the space. I think at the Cloisters [in upper Manhattan in 2013] it was really, really good, because of the textures of the walls, and it was a religious setting. But at the same time, we’ve had it in warehouses where it really sounds great. We’ve learned how to work with it, and which spaces work and which don’t.

George Bures Miller: We actually recorded Forty Part Motet in Salisbury, England with the Salisbury Cathedral Choir. We didn’t record in the cathedral, though. We talked a lot about what we wanted it to have when it was shown. The idea was that the voices would be very dead. There would be no reverb on them, because we wanted the reverb to come from the space that the work shows in. So, the producer found a space, a wooden space, still quite big, because it had to hold sixty people. We had sixty singers at the recording.

Janet Cardiff: Because the children’s voices had to do soprano, and their voices are weaker than men, so we added two or three children.

George Bures Miller: We covered the whole place with shipping blankets, which wasn’t the best solution as we know now. We have a lot better solutions that we could have done, but for a three-hour recording, it was the best we could do. Then we had each individual singer mic’d with small lavalier mics, and they had these little gooseneck things that came out and held the mic about six inches in front of them. We tried to space them a meter apart, so they were relatively spaced. But the problem that we ran into when we first showed it in Ottawa was the crosstalk.

We were working with these very rudimentary playback Tascam machines that had just been released. That’s actually what made the piece possible though, those twenty-track Tascams.

Janet Cardiff: Yeah, Tascam.

George Bures Miller: So, you had a small tiny LCD screen to edit anything on. You couldn’t see waveforms. It was like to edit all the crosstalk, we had to go through that in Ottawa on this little screen and with the score, because we had to figure out where we were. Twenty years later, someone wrote us and said, “You know, bar 25, whatever, of the sopranos in choir, six is missing. Why is that? Did you intentionally do that?” We’re like, “Oops.”

Janet Cardiff: But just a note on technology there. We quite often are on the edge of or making pieces that are making the computers chug along on the edge of working to their abilities. Even when we produced The Murder of Crows [2008], it has ninety-eight speakers. It was still difficult in 2008. Now, I mean, you could have, what, 1,000 speakers running on probably a MacBook or something. It is so easy now.

The Murder of Crows, 2008

Installation view Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany, 2009

Dimensions variable

Commissioned by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna for the 2008 Biennale of Sydney.

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York. Photo by Roman Maerz.

George Bures Miller: Well, we’ll see. Hopefully someone will ask us to do that piece, the thousand-speaker piece.

Barbara London: You have talked about Forty Part Motet having basically to be tuned to the acoustics of the gallery space. I know when you did it at MoMA and then at PS1, the angle of the walls was very important. I want to know something about how you work with what you call your “tonmeister.” Could you explain what he does when he situates and tunes the piece? I think that is indeed vital.

Janet Cardiff: Our tonmeister is Berlin-based Titus Maderlechner, who we’ve been working with for, oh my god, twenty-five years, I think. He is classically trained, so he can work with a symphony and say, “Okay, the sopranos are off on this bar.” But he’s also a musician and also a sound engineer. (He went through, I think, an eight year long program.) He can go into a space and just with his ears figure out, “Okay, the treble in this space is really harsh, whatever.” He basically takes his computer, gets the piece all wired up, and sits in front of the piece.

If I’m there with him, sometimes I help out, but basically, he can say, “Okay, take down the trebles.” He has a mixing board, and he’s able to tune the piece. So, a lot of times, we see our pieces as almost like instruments. Then quite often, a piece has to be tuned for the space, because the floors make a difference. The worst situation, I think, for a sound work is polished cement floors and hard drywalls, with, say, a nine-foot ceiling.

George Bures Miller: Glass on the ceiling is worse.

Janet Cardiff: Glass on the ceiling is even worse. Some of the modernist buildings are the worst for sound.

George Bures Miller: Every space also has a resonant frequency, and they all respond differently. Titus basically listens to the space, and he works with changing the bass. Some spaces just absorb all the bass voices, and you can’t hear them, and so you have to turn them up. Basically, we did that at first, before Titus. We discovered it ourselves. We had no way of tuning a work at first, and so we’d just go turn up the basses on the amplifiers. We had individual knobs on the amplifiers for each channel, and that was the only way…

So, we’d have one person in the back, and we’d be yelling out, “More soprano or less soprano.” We met Titus and worked with him on a couple of projects in Berlin. Then we were just asking him, “We have this choir piece. Do you know anybody who could actually tune a choir?” He was like, “Well, I could do that.”

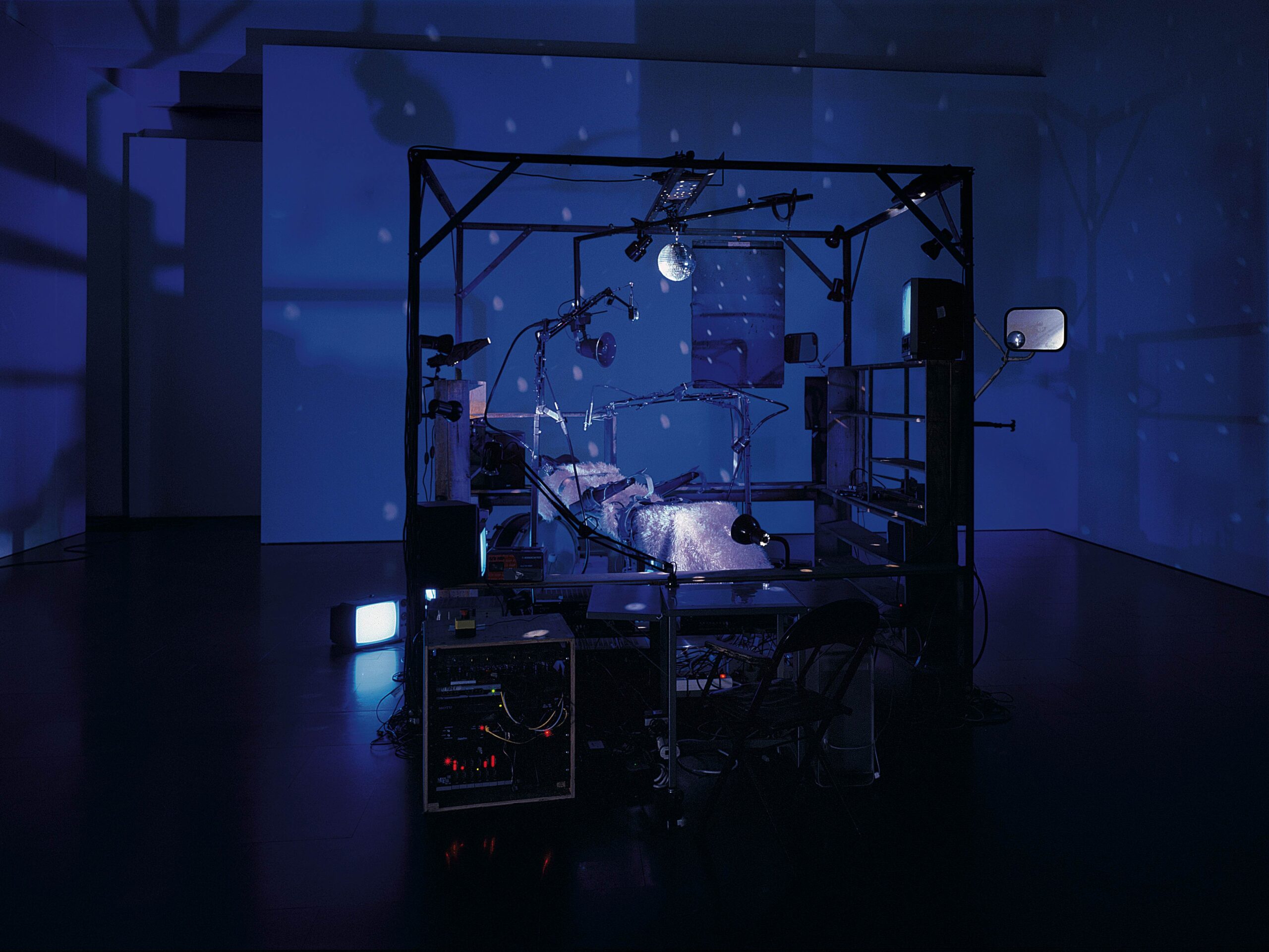

Barbara London: We’re moving along. I want to talk about two more works. As we’ve already discussed in regard to Tinguely, there’s a dark side to some of your work. The Killing Machine from 2007 is described as an automated ballet of robotics, props, light, and sound. The Killing Machine operates on an unseen imagined victim. The visitor is invited to activate the work by pushing a red button labeled “press here.” The work features two robot arms, which then perform a very grim dance macabre that entails needling an imaginary victim trapped in a dentist chair.

Pneumatics, robotics, electromagnetic beaters, dentist chair, electric guitar, CRT monitors, computer, various control systems, lights, and sound (approx. 5 min.)

Dimensions: 9′ 10″ x 13′ 1″ x 8′ 2″ (118 x 157 x 98 cm)

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York.

Photo: Seber Ugarte & Lorena López.

I think you’re alluding to part two of Franz Kafka’s 1919 short story In the Penal Colony, about an elaborate execution apparatus. The Killing Machine ironically contrasts the sinister activity with the rudimentary mechanics of a music box, and with playful embellishments like faux fur and a disco ball. As part of your continued exploration of theatrical tropes and immersive environments, this work brings to life a haunting spectacle that in its utility doubles as a critique of, maybe we could say, the sanctioned use of torture. I wonder how that work came about, and also the darkness.

George Bures Miller: Well, we were living in Berlin, so there’s that. I mean, in the winter time, Berlin is a dark grim place sometimes. I mean, I love it, but it was still dark. Janet had read the In the Penal Colony, and she gave it to me to read, which made me even happier. It was during the… The Afghanistan War and the Iraqi War were on, so the news was full of grim and horrible things like Abu Ghraib, the torturing, car bombs going off and killing troops on the side of the road.

Then to make matters worse, it was right when Errol Morris released a movie called Mr. Death (1999). It was all about someone who was trying to perfect the electric chair. It was a very dark, scary time that we were going through. So, we were talking about the Kafka story a lot, and then we were like, “Well, we can make our own killing machine.”

Janet Cardiff: Then we happened to be in London right after that. We went to [the Clink Prison Museum], the torture museum there, and we were looking at all sorts of things, which is typical of the way we have worked. Originally, we thought we would have eight of these robotic machines, and then it ended up as two, which was very nice, because they became characters that were almost like lovers at the end. They are choreographing and dancing with each other. But I wanted to say something about the Franz Kafka story and how potent it is.

No matter what decade we are in, it’s really, really sad that it’s super relevant right now, this idea of sanctioned bureaucratic violence, having this excuse for killing people, killing women and children, and slaughtering people. It just goes on and on. It never stops. It’s like Francisco Goya’s Los Caprichos [1797–1798 print series].

George Bures Miller: War is a war though, actually.

Janet Cardiff: Also, George Orwell’s novel 1984. As you can probably figure from our works, literature has a big influence on us. It is sad how an artwork or a story is still relevant. Our piece called The Murder of Crows was a reference to the war in Iraq or Afghanistan, and a requiem for the age then, and that was 2008. Now, it’s the same thing. I have to say that we have a lot of fun when we work in the studio. Even if we have a serious, almost black comedy that we work with, we also like to work with the viewer’s emotions. So that you can say something really heavy duty, but then you have a fun fur on it, or you have this disco ball that at the end is projecting images around, and becomes almost like a negative sun on the wall.

Then you have the disco stuff around. So, we try this sense of lightening up and comedic as well. Sometimes we use comedic opera in pieces that are very serious pieces, but it’s like the filmmakers the Coen Brothers. You reference how it’s pretty heavy-duty stuff, but at the same time have a sense of humor. We do laugh a lot when we are together, and working.

Barbara London: I remember very clearly being at documenta 13 in Kassel, Germany in 2012. Documenta is always a challenge, because there’s artwork all over the city. I remember dashing off and going into a wood to find and experience your work FOREST (for a thousand years…), situated outdoors. So, I’d love to know… You work in a lot of different situations, as you were just talking about. Could you tell me what you were doing there, and how you handled sound in an outdoor environment? I remember searching and getting near, headed for the sound, thinking, “Oh, I can tell where it is.”

22–channel outdoor audio Installation,

Duration: 28 minute loop

Commissioner: Curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev for dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel, Germany.

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York.

George Bures Miller: I was trying to think the other day, “Well, how do we decide to do a forest piece?” Did the curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev actually ask us to do something in the forest?

Janet Cardiff: Yes, I think so. Quite often, we’re given a site. Or we’ll go visit sites, and then find a location that seems to resonate.

George Bures Miller: But Carolyn just wanted to put a lot of work in the Karlsaue Park, right? So, then we toured the park for ages before we found the site that we thought was appropriate.

Janet Cardiff: We’ve always loved forests and all that. But then we started thinking about Kassel and the history of Kassel. What is this forest? So then it became its own narrative, and we didn’t have to add any language to the piece. We had this wealth of sound effects that went from all different eras of time, and nature sounds, and things like that, and people in the forest. It’s basically kind of a collage.

George Bures Miller: We’d been working with this technique that was invented in the 1970s by an English mathematician, called Ambisonic Audio. Michael Gerzon [1945–1996] is the inventor, if any nerds are out there. But anyways, it uses one microphone, and from that microphone you can decode any number of loudspeakers. We recorded sound effects with this ambisonic microphone. We went all over the place, to people blowing up things. We hired someone to blow up stuff. So, we set up a sphere of loudspeakers in this forest of twenty-four speakers, something like that. They’re up in the trees and around you, and they’re quite small, but very powerful loudspeakers.

Janet Cardiff: Then when we were mixing it, if you record in a forest, you have to really replay it in the forest to see how it sounds. So, we share a place out in the West Coast of Canada on Hornby Island. It has a forest, so we went there for three months, and set up an array of speakers in the forest. Our neighbors would hear these crazy sounds coming from it. Basically, we edited it there, because we had to edit it outside on site, because sound doesn’t transfer. You can’t mix this in your studio, where you can do a really rough mix.

Then we think, “Oh, this part’s going to be great. It’s going to be great outside.” Then we take it outside, and it just falls flat. So, I think everything we do is always teaching us about ideas of sound, and making us more sensitive to the complexities of it.

Barbara London: But I wonder if out in the forest, you’ve got the birds and the bees and the wind, so, it’s not controlled. You’re controlling, but it’s uncontrolled out there.

George Bures Miller: Well, we worked with that in the piece because we have a storm come in. You hear the rain, the leaves moving. It might be a beautiful sunny day, but I’ve seen people get their umbrellas out waiting, because they hear the rain coming down. It’s like, “Well, it’s not coming down.” So, we used that, and we used a lot of bird noises coming and going. It was interesting, because in Kassel, we had these birds from Hornby Island on the west coast of Canada, these ravens. The crows would come to the forest in Kassel, and they’d be sitting there listening to these ravens going, “What? What is this?”

Janet Cardiff: It was like, “I don’t understand their language. What do they say?”

George Bures Miller: It’s amazing how intelligent crows are. They were so puzzled by this foreign bird sounds in their forest.

Janet Cardiff: But then we did a talk at a local university, and there was a forest next to it. So, part of the agreement was that we could use some of the students out in the forest making sounds. So, we had people screaming, people running, and then we did a reference to a Philip Glass piece where there’s the knocking on wood. Then we had students all take a piece of wood, and knock on each tree, and make this composition. It’s very similar to the Walks in how you record in the same location, and then if you replay it in the same location, you really don’t know what’s real and what’s not.

George Bures Miller: That’s what we were trying to go with, and that’s why we researched this ambisonic audio. It is now getting more and more popular, interestingly enough, because it can be used inside of virtual environments. But when we got into it twenty years ago, it was 2005 when we did Berlin Files. That’s when we first bought our first Ambisonic mic, and it was such a rare thing. Now, the software and everything is so great. It’s just amazing what you can do with it.

Mixed media installation; Wooden panels, video projection with 12 channel surround sound audio, looped

Duration: 13 min.

Dimensions: 9 x 7.5 x 3.5 meters

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York.

Janet Cardiff: But one of the things I remember seeing was a dog. We have video footage of a dog sitting there with its owner sitting and listening to the piece. The dog is just looking all around going, “What the heck’s going on?” Kids do that as well, because kids don’t have the same filters. Once you get older, you’re able to understand the difference between reality and fiction. Well, sometimes we are. We don’t know about the news.

George Bures Miller: Not anymore.

Janet Cardiff: Children will just look around, and try to find where the sound’s coming from.

George Bures Miller: Children really react to binaural audio, too.

Janet Cardiff: They really do, because children love to play.

Barbara London: So, here’s one of my last questions. Today it seems that the boundaries between mediums is broken down, and you could say interdisciplinarity is the norm. I know you work with many different things. What would you say your medium is?

Janet Cardiff: It’s very funny about ideas around medium. I did my masters in printmaking, and then I’d get invited into printmaking shows. I just hated it because I don’t identify per medium, because it’s about the ideas, or it’s about what it’s doing to you. I don’t think we’ve even been in shows called sound shows…

George Bures Miller: We must’ve been in some sound shows.

Janet Cardiff: I don’t think so. But anyways, I think we’re hybrid artists. We work in theater tropes. We work in filmic tropes. We use techniques from music and narrative literature. So, I think it was just natural for us, because when we were first meeting, on our first date practically, we started collaborating together and just having fun making videos. George was actually going to be a filmmaker, and we did produce one sixty-minute Super-8 film. It’s about a detective and had a car chase and everything.

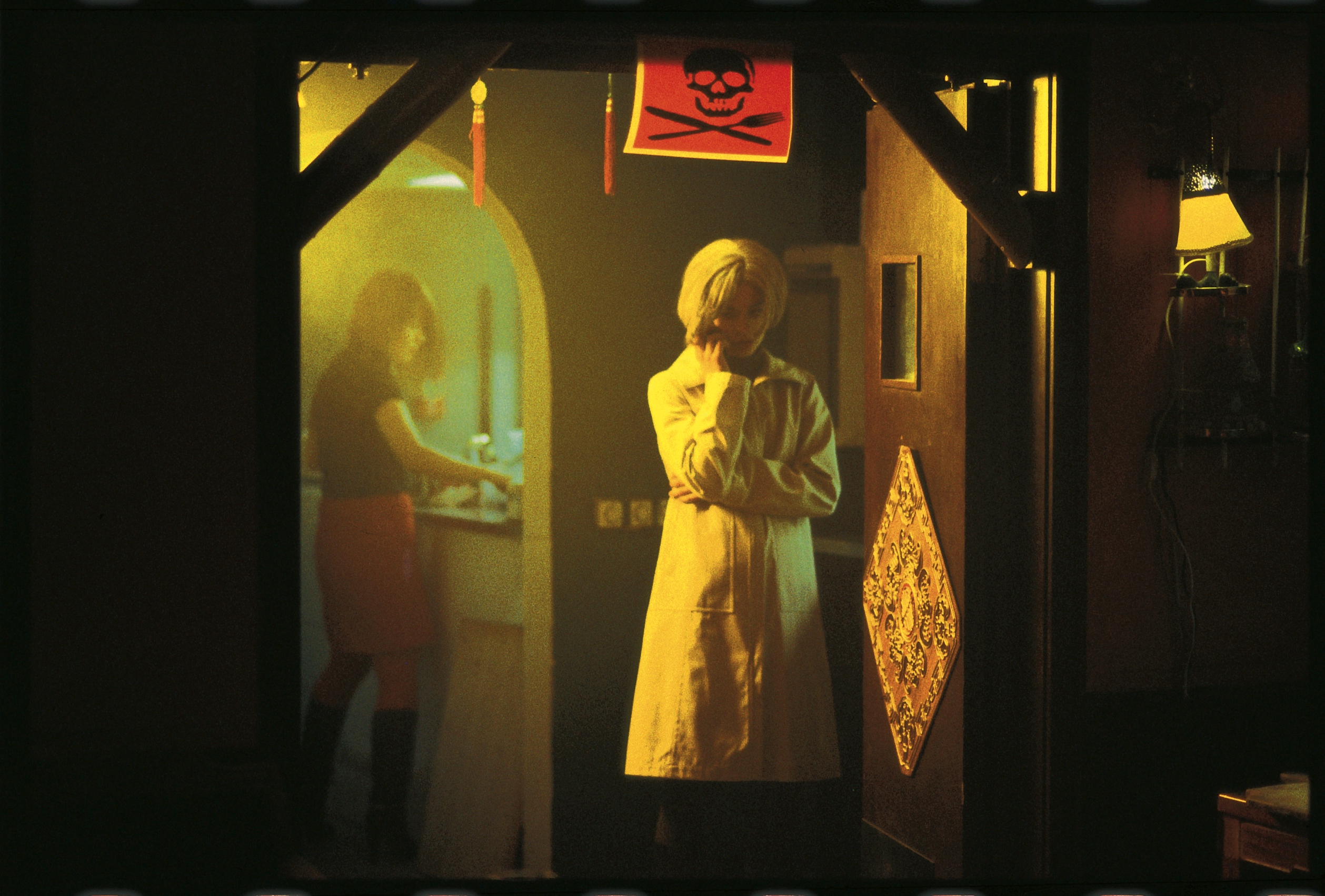

Then we realized that we don’t really like working in such a tight system. So, we realized that the art world is much more interesting, because then you can still reference filmic ideas. You can do things like the Paradise Institute [2001], that’s like compressing a film into a cubist setting. You can play with it, right?

The Paradise Institute, 2001 (video still)

Wood, theater seats, video projection, headphones and mixed media with binaural audio 118 x 698 x 210 inches (5.1 x 11 x 3 meters)

Duration: 13 minutes

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy of the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York.

George Bures Miller: I think though we’re sculptors.

Janet Cardiff: Yeah, that’s true.

George Bures Miller: I mean, even if it’s a purely sound piece, it’s always sculptural sound. Kasper König recognized that with your audio walks. He puts you in Skulptur Projekte Münster saying, “This is sculpture. This walk is a sculpture.” So, I think, purely, a Walkman piece is a sculpture. Well, that’s a weird thing. But I think our interest is really in things that surround us, that are three-dimensional, that we can go around and can explore.

Janet Cardiff: I remember reading a quote from Henry Moore, who talked about walking around a sculpture. Your view has changed. I always liked that idea that it’s through time and different perspective. Then everything’s changed about the sculpture, that you can imagine. So, it’s the same thing translating to audio.

George Bures Miller: It’s interesting that we received the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize [2020] for opening up new perspectives for sculpture.

Janet Cardiff: Yeah.

George Bures Miller: We were like, “Oh, that’s cool.”

Janet Cardiff: That’s true. The sculpture prize, that was very interesting.

Barbara London: This is what I want to ask you in conclusion. The aesthetics of what you are working with is quite complex. Your work involves technology, meaning hardware and software, both of which need upgrading all the time. This is last thing I want to talk with you about, because as you have worked, the art world and technology have changed so much and will continue to change. I want to know, do you worry about the future, and what are you doing about the future?

George Bures Miller: We worry about today, I mean, because basically, we’re living in the future right now, because a lot of our pieces are twenty years old. So, we are having to upgrade them, or figure out how to migrate, as we call it.

Janet Cardiff: Quite often, we can’t migrate them.

George Bures Miller: Exactly.

Janet Cardiff: Because the software that worked in 2008 on the old Mac doesn’t work on the new Macs, so that our pieces won’t work without that. It’s really, really difficult actually. We’re buying retro computers.

George Bures Miller: Yeah, we have a stockpile of old Macintoshes from fifteen years ago, the desktop Macintoshes that most of our old pieces run on. But I mean, there are ways. We’re still… I’ve got some ideas.

Janet Cardiff: Okay, I’ll let you go.

George Bures Miller: I mean, I’ve got some ideas. I’m not telling that…

Janet Cardiff: Oh, good. Good. Good. You’re sharing with me.

George Bures Miller: We’re going to figure it out how we can upgrade.

Janet Cardiff: We have stacks of hard drives just all over our studios.

George Bures Miller: Oh my God. The people who do, they take the time, and they are doing a lot of hard work on trying to figure it out, as well. I think any museum that collects media work like film or video, film maybe not so much because you can actually put it in a can, and it’s going to be okay in sixty years. But video, especially from the ’70s… So now, you have this digital thing, and you’ve got hard drives that you have to deal with. It’s a weird… Everybody’s having to deal with it, but I think we rely so much on control systems like motion and moving things and lighting changes now, that I’m hoping that there’s going to be theater software that we’ll be getting.

I mean, it’s almost the most appropriate thing for us to use now. We used to cobble together a lot of stuff, and just make it work. Now, everything changes so quickly. It’s weird, isn’t it?

Janet Cardiff: But then it’s like a similar problem of say some of the Rauschenberg paintings or whatever, some of the cardboard things that some of the artists have worked on, and the difference with the old-fashioned oil paintings.

George Bures Miller: Well, even right down to light bulbs, you can’t get the bulbs that we use for Opera for a Small Room [2005] anymore. We’re having to figure out what to do with that, and TVs, cathode ray tube televisions and all these different things.

Opera for a Small Room, 2005

Mixed media installation with sound, record players, records, and synchronized lighting

102 2/5 x 118 x 177 inches (260.1 x 299.72 x 449.58 cm)

Duration: 20 Minute loop

© Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy of the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York.

Photo credits: Markus Tretter

Janet Cardiff: Several artists are in competition for those on eBay.

George Bures Miller: Yeah, we’re all bidding against each other to get the cathode ray TVs. I don’t think we can compete with Nam June Paik’s team.

Janet Cardiff: No, I don’t think so.

Barbara London: There are two things. One you’re lucky, you’re in Western Canada. I’m sure space is still at a premium, but you have a space where I believe you’re keeping your work operating. So, when curators are doing research for a show, they can visit and can actually see work. The second thing is, I talk sometimes with the Getty, which has a strong conservation staff. Because I’m from MoMA, also with a terrific conservation team, I know there’s a lot of effort there going into this. It’s not simple at all.

George Bures Miller: No.

Janet Cardiff: No, it’s not simple. I’ve been at some of those conferences, talking about even the cloud. What happens if all the certain countries where the whole cloud is stored, and in this building or on an island or something, and then all of a sudden there’s the rise of the oceans, or there’s a flood or something like that. Which affects that.

George Bures Miller: It’s just such a challenge, that whole thing, even just storing your work…

Janet Cardiff: I did want to connect to what you said, if we can give a plug about our building in Enderby, BC, where a lot of our work is in storage all the time, because we keep an artist’s proof of most of the works. If it’s in crates, we never get to experience our own work. We learn from our work, and we always make work for ourselves. We make work that we know we would enjoy. If we don’t enjoy it, then it’s not a very successful work for us. So, we found this building in Enderby that is almost 20,000 square feet with almost 20-foot ceilings, and decided to open it to this rural public.

It’s been such a satisfying experience, in a way, because you have people who really will never make it to the MoMA, will never make it to even Vancouver to the Contemporary Art Gallery. They’ll come in, and it’ll be something they’ve never ever experienced before, because they always thought art was landscape painting or a drawing, or a sculpture, a plop sculpture or something like that. We want to do this as an educational thing, but it’s been a really fun experience. I hope, Barbara, one day you’ll be able to come and visit and see it.

Barbara London: I will be there. Don’t worry.

George Bures Miller: Part of what it was for us, I think, is both Janet and I grew up in rural environments, and we both had experiences as young people with cultural groups that came through our towns that changed our lives. So, we thought, “Well, if we can do some small thing like that for some individual, it would be a great thing.” The plus is we get to see our work, and have it up.

Janet Cardiff: Ironically, before what we were talking about the Forty Part Motet, we have an exhibition copy of it in our building. One man told me that he was able to listen to it a couple times the other day. He texted me this, and then he said on the way home, he had to pull over, and he just started weeping. He said it brought out something in him. He didn’t know that there was a problem, but he just brought out all this emotion. We have had all sorts of people telling us things about different pieces, with The Murder of Crows, with the 98 Speakers — just different experiences, and that it’s really affecting them. We just love it. We don’t love that people have problems, but…

George Bures Miller: We love that people are crying on the side of the road. [Laughs]

Barbara London: Well, what you’re doing is fantastic. I think you both are remarkable. I want to thank you so much for talking with me.

Janet Cardiff: Thank you so much for doing a series like this. It’s great.

George Bures Miller: It’s fantastic. Thank you for having us, Barbara.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Ryan Leahey, with audio engineer Amar Ibrahim and production assistant Sharifa Moore.

Support for Barbara London Calling 3.0 is generously provided by the Richard Massey Foundation and by an anonymous donor.

Special thanks to Masayoshi Fujita and Erased Tapes Music for graciously providing our music.

Thanks to Independent Curators International for their help with the series. Be sure to like and subscribe to the podcast so you can keep up to date with new episodes in the series. Follow us on Instagram at @barbara_london_calling.

Web design by Sol Skelton and Vivian Selbo

This conversation was recorded December 13, 2024; it has been edited for length and clarity.