[January 26, 2022 | Season 2, Ep. 6 | Barbara London Calling]

Barbara London: Today I’m speaking with Nalini Malani, a versatile artist who easily moves between the mediums of painting and video, and between the cultures of Bombay, as she still prefers to call it, and Amsterdam. Born 1946 in Karachi, British India, her Sikh agnostic parents and family fled during Partition, in 1947, to Bombay before settling in Calcutta. After a job transfer of her father to Bombay, Malani studied at the conservative British style Sir J.J. School of Art, where in 1969, she received her diploma in painting.

During her studies she already had a studio in the multidisciplinary Bhulabhai Memorial Institute, Bombay. There, she interacted with actors, musicians, poets, and dancers, and saw how theater reaches an audience rarely found in the elitist gallery spaces. That summer, in 1969, she was selected to be part of the renowned Vision Exchange Workshop, VIEW. As the only female participant, she became its most productive member, creating a large series of camera-less photographs, experimental 8mm color stop-motion animation and a series of short black-and-white 16mm films. From this, she developed a filmic view that would dominate the rest of her artistic life in all the different media she used. Nalini, thank you so much for joining me.

Nalini Malani: Hello, Barbara, it’s lovely to see you and it’s lovely to talk with you this afternoon. We’ve known each other for a long time, but it’s lovely to meet across oceans at this moment. At least that’s possible.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: Let’s begin with your early interest in the moving image. Growing up, you were inspired by the documentary work of local filmmakers and photographers. I’d love to know if you and your friends engaged in heated dialogues about movies, and if you assisted each other with your very early efforts at filmmaking?

NM: When I was in the Sir J.J. School of Art, we already had cine clubs in Bombay. The good thing was that we were able to see a lot of European and East European cinema, as well as, of course, Asian cinema, Japanese and what was coming out of China, to some extent. But also, some of the alternative cinema that we had in India as well, which didn’t ever get shown in the big cinema houses. The movie houses largely showed American, Hollywood films.

Of course, there was much heated discussion about this new kind of cinema, new for us, that is, French nouvelle vague and also the neorealism from the Italian filmmakers. But when I started to make my own films, I’m afraid to say that I had no support from other colleagues at VIEW. It was all by myself that I made these films [Dream Houses, Still Life, Onanism, Taboo, Utopia].

This is how it was. What was very interesting is that there were a lot of documentary films, which again, didn’t get distributed in the cinema houses, but we did get to see them at these cine clubs.

BL: I gather you were determined to maintain a hands on, in other words, a tactile practice. You became an accomplished draftsman. For the newspaper, The Times of India, you created illustrations that accompanied short stories written in Hindi by very young writers. Their newspaper stories drew on such epics as the Mahabharata and Ramayana, but the young writers who recast the familiar characters in a contemporary context. I’m curious, how did the writing of these young writers fuel your interest in literature?

NM: From the age of eighteen to the age of twenty-three, I was at the art school. The Times of India gave me the chance to make these illustrations for the short stories that the new young writers were bringing out. The interesting thing for me was the connection of the short story writers and the playwrights, who also were working with Hindu mythology and using it in a contemporary way. This was connected to the kind of work I was doing at the Bhulabhai with the theater directors, who I was assisting backstage, et cetera, when the theater projects were on. And so, there was a connect there between the writers who were being published at The Times of India and the playwrights whose work was performed at the Bhulabhai. This also led me to understand how mythology can be, let’s say, given new avatars in the contemporary world. This again triggered my need to get into narrative and storytelling in my own way, which has lasted up to today.

BL: Wonderful. It was in 1970 that you received a scholarship to study in Paris, and it was there where the Ecole nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts was closed. You were able, still, to develop your own program of study. This resulted in working at the Atelier Friedlaender with an emphasis on printmaking. With the spare time that you had left, you extended your studies by attending lectures at the Sorbonne. The luminaries you heard were Noam Chomsky, Claude Levi-Strauss, Charles Bettelheim, and you attended screening and discussions at the Cinémathèque Française, with Jean Luc Goddard and Chris Marker. And you joined the political activities of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. This must have been a truly extraordinary time. So, looking at my question from another angle, how did this dynamic time in Paris affect your understanding of India?

NM: Often it’s when you are out of your own country that you get another lens in which to look at your own country. And this was a very good time for that. Also, I always consider being in Paris the university of my life, because it really taught me a lot, especially because it was soon after ’68, soon after the Student Revolution, and this was a whole new way of living, let’s say. The most important thing that happened during the time, apart from the scintillating lectures at the Sorbonne. It was the first time I was listening to Noam Chomsky, and for me it was just a real prise de conscience, let’s say, and also Claude Lévi-Strauss with his new ideas on structuralism, which I think was a very dynamic theory. I also came to read an extremely detailed work called Homo Hierarchicus by a socio-anthropologist Louis Dumont, who had done enormous work on the caste system of India.

I had no clue at that time, how the caste system really functioned in the earlier years of this nation, and how it was still operative, and the aggression in it. Hierarchies of class we do know about, and hierarchies of class are also extremely aggressive within each other. But caste gave a whole other kind of idea of what can happen when ideas get so fragmented. The other thing is so fragmented that you keep making enemies within, let’s say. The other very important thing, which again connected to other things, was working with the Atelier Friedlander. Friedlaender, himself, was an enormously talented engraver and printmaker, but he had also been in the resistance. I had seen films about the Second World War and about what had happened with the Holocaust, et cetera, but here was somebody who had been there. He used to ask me to come with him with his plates. I used to follow him with these large plates, copper plates, to the print makers. He would walk ahead of me in his white laboratory coat, and just go on a monologue about the war. It was like a whole world opened up about exactly how it was. And this connected to what other than really is even still today in large parts of the world, but in India, especially, so.

BL: I think there’s another artist that had an impact on you. I want to ask you, how was the Mexican painter and muralist Diego Rivera an inspiration to you back then?

NM: Well, what Diego Rivera became was a model, in one sense, because, first of all, he went back to Mexico, just like I went back home. When I went back to India, India was a new country and there was much to be done. There was much to look forward to in terms of image making and art making. I think Diego, in that sense, was a model. Plus, he was also a revolutionary, and the kind of work he did in painting was really a kind of painting of the people. In that sense, in many ways I see a kind of a relationship between Mexico and India. But next to that was Godard who also provided a similar kind of model, because I remember going to lectures at the Cité. He said, “I’m now going to stop with filmmaking in Europe. I have a Portapack, and I’ll go to Palestine and I’m just going to record that history.” This was a whole other way of working it out. Both of these characters, Diego in his own way and Godard in his way were great inspirations.

BL: After this amazing period in Paris, you returned to Bombay in 1972, and you set up your studio in an area known as the Wholesale Market, Lohar Chawl. You didn’t pick up a brush again, but you started a documentary set in a Muslim slum. It was a kind of consciousness raising project that unfortunately you had to abort, due to the unexpected overnight demolition of the slum. In 1973, you made a silent black-and-white film called Taboo, while assisting the director Mani Kaul with a film set in a village in Rajasthan. I would love to know the backstory of your very beautiful short film Taboo.

NM: With Taboo, I was filming a woman who was working with her husband. They were weavers, and the weaving community is a certain caste. Their caste means that they cannot mingle with the caste that is higher to them, and certain things are taboo, especially for women. Within the family itself, there is a bifurcation. She was allowed to spin the cotton and wind up the thread, but she was not allowed to touch the loom. The loom and the creative part were only handled by the man. I felt that this division seems so unfair and unjust, because, as we know very well, the creativity of women is enormous. And then, whenever she was in front of her husband and I was shooting them, she would always completely cover her head, the face, as if I should not see her exposed face in front of her husband.

All of these aspects are finally what made up the film called Taboo; because talking about caste, woman is a separate caste in India. And shall I say that taboo against women is enormous, even till today, as you might have already heard about the rapes that are taking place. Also, that it’s finally, the extreme orthodoxy is orthodoxy that is imposed on women, and it’s they who have to wear the accoutrements of the religion, as we now see in Afghanistan. This has been, let’s say, a way of bringing forth these subjects, which remain quite hidden, in some sense. I’m really very keen to use such a subject for talking about. And also, it’s the subaltern that has to speak, and these are subalterns.

BL: The title is perfect, Taboo. Let’s move on. Filmmaking is not cheap; you record on film; you have to send it out to be developed. There were certain financial constraints and that led you back to make paintings. And that led to a contract that you got with the Pundole Art Gallery. In the 1970s and 1980s, this resulted in different series of paintings, that you say were all based upon a filmic view. You consciously use different filmic perspective as if the paintings were made with a close-up, a mid-shot, or a long-shot lens. It was in the 1990s that, for the second time, you broke out of the painting frame, as you did in 1969. You started to make large scale wall drawings, theater projects, and for the first time in India, multichannel video projections. I’d love to know what that transition was like for you?

NM: Yes, it’s true; I had to start to make paintings because how else to live? Except of course, I could take a job as an art teacher in an art school, but such jobs were scarce. So, I started to make paintings, but my obsession with the moving image was enormous because in India, if you show a video or film, people are very attracted. My endeavor has always been to show in places where people can come and watch. It’s always the moving image and the sound that attracts, but it was not possible at that time. My obsession with the moving image was actually the reason for using the film view, and many times in a series it was like a storyboard. There was a series called His Life about a man in Lohar Chawl, his life as constructed in a fictionalized form.

But when I started to work backstage with the theater projects, when I was a student and had a studio at the Bhulabhai Memorial Institute, let’s say, the main pivot at that point was what I wanted to do with memory. And memory in theater is very important, because you finish seeing a play, and it is in your memory. You talk about it, what you remember. And similarly, when I started to make wall drawings and video plays, this was one of the main things that I wanted very much to emphasize. The reason is that you must go away with your memory of the event, and it starts to work in your own system, in your own psyche, and that’s how you remember it. Memory as the main idea of theater, wall drawing, and also the video plays is the crux of what I wanted to do.

Coming out of the painting frame was also one of the reasons why I wanted to go more into a public space to show the works. This is what I did in the very first video play I made called Remembering Toba Tek Singh. It was in what is now the former Prince of Wales Museum, where 5,000 people visit every day. It’s a natural history museum plus a sculpture museum, with sculpture as in ancient sculpture. There are school kids who come, and there are many people who come from small towns, as well. This was the ideal setting for showing such a work.

BL: This takes us right to another work. The actor Alaknanda Samarth introduced you to the work of Heiner Mueller, who’s considered one of the great dramatists of death. He saw history as an unending slaughter, the work as a scene of devastation. That led to the collaborative work, your Medeamaterial [1993] supported by the Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan Mumbai. You made a series of artworks that included wall drawings, which are now in the collection of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. The mediums of that work include a neon sculpture, reverse Mylar paintings, videos, slide projection, and I think a few more. In the evening, the full-fledged installation in the exhibition would become the site for the performance by Samarth. Afterwards, you directed a 56-minute single channel piece with the same name, Medeamaterial. How did this work mark a turning point in your career?

NM: I love collaborations, and working with somebody so dynamic as Alak (we call Alaknanda “Alak” for short) was an amazing experience. I always feel a collaboration leads to something else, something outside of her and me. So, a third thing happens; we are like catalysts who bring a third aspect out, and this was what actually happened. I actually started to make these installations while she was in London, where she lived. Before she arrived for the rehearsals, I’d already started to make the wall drawings and all the other aspects that I wanted as the exhibition. She came, and she interacted with them. I think “in painting,” and it’s painting that extends into other ideas. So, the crux of an idea is in painting and drawing, and then painting extends into things, like Mylar painting, Mylar cylinders, wall drawings, et cetera. It led me to really work within the text. Ever since then, I have incorporated Mueller’s texts in many other video plays.

And also, I think that the way he captures the idea of the twentieth century aggression of our civilizations, which I think some that’s still ongoing. We still have to talk about it, and Mueller does this extremely well. He combines Brecht with Artaud. In the script, you see the classic language of say, even Shakespeare in Hamletmachine, but you also see the scratch of graffiti. This combination was very inspiring, that you could have the high and the so-called low, and make it into something else, which would make that graffiti level of language acceptable within the whole. Mueller taught both Alak and me a lot. We have worked on Mueller in a number of other works, including Unity in Diversity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5BNgrKjPLbc

BL: I like the reference you make, going from Heiner Mueller, to Brecht and Artaud; it’s nice. I want to now turn to when we’ve first met, which was in 2002. You had come to New York for your solo exhibition at the New Museum, where the central piece was the four-channel video play Hamletmachine of 2000. You had adopted fragments of Mueller’s play from 1997, when Germany was divided into East and West. A few days before your exhibitions opening, you invited me over, and I watched you assemble a pure white bed of salt, which was to become the screen for the fourth projection. This portrayed the bloody violence that grows out of myths of victimization and redemption, causing disenfranchised groups to turn against one another with really horrific results. Violence is a persistent subject in your work, both its unforeseen presence, and its universality. Can you tell me what draws you to violence as a subject, and why the choice to make work in a medium that you call, “video plays?”

NM: Well, I love theater. But it’s not possible to do theater in India, because you just don’t have state support, or any other kind of support. After we finished working on Medeamaterial, I did one more collaboration on a Brecht story called The Job [1997]. After that, we couldn’t travel the play. I mean, we just had a few performances in Bombay and then in Delhi, and that was it. Of course, we couldn’t sustain actors; how to pay them, et cetera. So, it was out of a poverty of means, or a poverty of what was not possible that I decided to have an actor work for me in a video play. This would be totally possible, for a one-time performance. Remuneration would be only for that period; carrying a few video files was the ideal way of showing video plays.

That’s why the one that you saw, Hamletmachine, had the Butoh dancer from Fukuoka, and he performed for me in Hamletmachine. It was my love for theater that I extended into video plays. Then the plays themselves, I could put in painting, and I could put in animations. I could do a lot. Video really expanded my idea of theater in a huge way.

In terms of violence, there’s a beautiful poem by Wislawa Szymborska called, Everything Is Political. The water you drink is political. The leaves that you see on a tree are political. You walk down street, it’s political; the water that you get in your pipes, and everything that society can give you has come from a political action. Politics means also the underside, the underbelly, which is violence, because it’s often out of just as much as we, as women, had to fight for our rights for voting, we had to fight for our rights to abort if we didn’t want children. All of that needed a protest. And sometimes, the protest would become violent, not because we were violent; because the persons who did not want change were perpetuating violence upon us.

These are things where violence can be nuanced in several ways. It’s not so much as if one wants violence in a society, but one wants to have a peaceful society. The very fact that even today, we have such a lot of aggression around us. In one sense it is sad, because here we are talking to each other because of beautiful technology. We are speaking to each other over oceans; we have phones that can connect us to anywhere in the world. But when it comes to the human psyche, being abreast with the technology that science has given us, we have failed. We still have a mentality, which is primitive.

BL: The concept of primitive is very interesting. I want to move onto how women from Indian and Greek mythology often appear in your work. This includes your Sita/Medea paintings, which you began making in 2004, and your 2012 video work In Search of Vanished Blood, which refers to the mythical seer [from Greek mythology], Cassandra. I’d love to know what distinctions you see between painting and video?

NM: I always say that I draw, I paint, therefore I am. For me, drawing and painting are like keyboards. And from then on, I can start to compose the videos, and choreograph the videos as the video shadow plays. The second question you have is about the characters, Cassandra or Medea. There are instances, examples of the Greek myths in Indian mythology, as well. I think people tend to forget that the army of Alexander stayed on, along the borders along Afghanistan. In fact, the Bamiyan Buddhist sculptures were in the Hellenic style, the ones that were destroyed [by the Taliban]. We actually have a school of sculpture, the Indo-Hellenic style. There are lots of references in one and the other. So, if there is Sita, Sita is very much like the character Medea. And as Cassandra is a seer, so also in Indian mythology we have a seer, Sahadeva. He was a male. He could see into the future, but you had to ask him the right question. Otherwise, he could not answer you. So, it was very similar.

There are many of that kind of connections. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, people are turned into different animals, or monsters, or whatever. In Indian mythology we have similar resonances. So, there’s a lot of parallel things happening between Greek and Hindu myths. I must cite a dear friend of mine, Thomas McEvilley, who has written an absolutely fantastic book on this comparison of Greek and Hindu myths. [The Shape of Ancient Thought]

The other thing I wanted to say was, apart from Cassandra and Medea, I’m very interested in visualizations of other artists who have worked with the idea of violence, like Goya. In fact, in In Search for Vanished Blood [six channel video/shadow play, first shown at dOCUMENTA(13) 2012] the animations quote Goya’s Disasters of War, and also Rembrandt. Rembrandt’s drawings, particularly the peeing man, and there are two or three other characters that appear in the animations as quotes. It’s also to bring forth what artists have done before me. And again, trying to understand. Look, this happened two centuries ago, and this is happening now.

In Search of Vanished Blood. 2012. Video (color, sound), 11 min. Image, courtesy the artist.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uK9iRoPds8&t=91s

BL: Your interest in history, the past and the present, strikingly came together in 2003 at the Istanbul Biennial. It was there, that I saw the first iteration of your work Gamepieces from 2003/2009. The installation was incredible. It occupied a magical spot: the underground Basilica Cistern, which still collects rainwater 1000 years after it was built in the Roman era. Gamepieces appeared to represent a sort of detente between fractious religions, centering on the healing powers of myth. To describe it, the installation consisted of rotating Mylar drums, each six feet high. On the interior surfaces of the six transparent cylinders, you had painted a chaotic battle scene with all kinds of creatures: Byzantine angels, boxers ready to fight, monsters, war planes, guns, human skulls. These familiar symbols of war came from different cultures and periods, and all function as metaphors for an embattled world. I’m very happy that a few years later, the work entered MoMA’s collection. Your ideology reminds me of another artist, and that’s Nancy Spero. Born 1926, she sadly passed in 2009. She looked at aggression and victimization with quite unflinching eyes. Did Nancy Spero have an impact on your practice?

NM: I met Nancy in 1979 on Wooster Street in the A.I.R. Gallery. This, for me, was a momentous occasion. I walked into the gallery with my friend Judy Bloom, and she said, “I want you to meet Nancy Spero, Ana Mendieta and May Stevens.” So, you can imagine, that is so vividly etched in my mind. The talk we had was very inspiring—and the fact that there was a women’s gallery. And yes, Nancy Spero has been a great model for me, and also her husband, Leon Golub. Both were people of the left, constantly speaking about the aggression of society and the impact on the disfranchised. Also, what A.I.R. gave me, what these women artists said: “We have no platform, so we made our own platform,” which was the A.I.R. Gallery. I think it’s about time somebody wrote about this in detail, even as a PhD thesis. It’s about time.”

I came back home and I said, “Well, we have to do something like that too,” because we also in India have a similar problem. Women artists are not treated on par with the male artists, and we don’t get chances, and most times we are just ignored, as it also happened to me, when I was working at VIEW. I tried to gather together a group of women artists. I had about fifteen names, and I tried to get funding for it; but it was totally impossible. So finally, an artist a little senior than I am said to me: “There are four of us, and we’re the about the same age. Let’s just do it together.” And that’s what we did as a group of four artists. We had five shows together, traveling second class on the trains throughout India, carrying our babies on our hips. Absolutely, Nancy, Ana Mendieta, May Stevens, all of them had a great impact on me because of A.I.R Gallery. But Nancy’s own work, I adore her work, which is absolutely superb. The last work that I saw of hers was in the Venice Biennale when Robert Storr was curator and featured her installation, the Maypole (2007). Unfortunately, she was too ill to travel. But it was great to see her work there. Hats off to Nancy; she’s really special.

BL: Well, you’re very special, too. In 2010, I was very happy to see your exhibition at the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne. I attended the closing performance of your exhibition, “Splitting the Other.” [Title comes from the 14 panel painting installation which Storr showed in Venice 2007.] I’d never been to such an event. We joined altogether in a room, where four of your mutant paintings from the 1990s were combined with large charcoal wall drawings. It was a surprise that we, the audience, were asked by the Director of the museum to be the performers of an erasure performance. We all were given an eraser and a stamp on our hands that spelled in capital letters, “D.E.M.O.C.R.A.C.Y.” We all proceeded very carefully to obliterate your drawings, as a classical Indian music composition was played. It took a while. Do you want to tell me about this concept of wall drawing/erasure performance, which you started in 1992?

NM: The wall drawings started with two ideas. One was the idea of memory, as I had it in theater. The first wall drawing I did was in Bombay, in a gallery where hardly anybody from the street comes in. I worked for ten days in the gallery. By word of mouth, people started to say, “Something is happening there.” Even the person who sells peanuts around the corner came to visit me, which was great. And the people came, and sat, and they talked to me, and they said, “Why you are not doing this right?” They criticized me. And they said, “You don’t have this hand right. You have to do it like this.” It was a great interaction when I actually made the drawings. Then they would come to visit, when it was all done. But after fifteen days, I erased it, and they wept. They said, “Oh, but why can’t it be here permanently?” For me, it was a wonderful time when I say that people who can’t afford to buy art, people who are just off the street, people who are just vendors on the street, they are interacting with this. It was a very heartening moment for me.

But the other thing was that, in India, the auction houses came, and the value of art was all people were talking about, value as in prices. And the newspaper critics had stopped writing. Newspapers had stopped commissioning critics and reviewers; none of that was happening. There was one superb poet, Nissim Ezekiel, who would write the most exquisite column reviewing art, but all of that was gone. And I felt that the India and the Bombay I knew, the vibrant city with all this culture and zeitgeist, was slowly fading away because of commerce. And then the fact that artists stopped talking to each other; they stopped meeting at each other’s studios. That’s what commerce did.

So, in one sense in order to combat that, I started the wall drawings where you had art for free. No artist price list! So that was my idea, and I continue to do that even until today. Interestingly at the Centre Pompidou [The Rebellion of the Dead, retrospective, 2017], the curators and everybody who worked in the galleries would watch me drawing every day, for ten days or so. Then, when it came to erasing, I asked the director, Bernard Blistène, the curator Sophie Duplaix, and some other people [who worked on the exhibition] to erase with a bunch of red roses that had died. The color came on the wall, and they were crying as they were removing the drawings. So, it’s been a very good way of working. When you’re up very close to a drawing, then you see it in another detail.

Also, I always say, when erasures take place, don’t worry, you are not destroying, you’re also creating. That’s because the eraser makes a white line, so you erase and also draw simultaneously. So, it’s not considered obliterating. The other thing is democracy. I’m obsessed with democracy, and even have addressed it in In Search of Vanished Blood, by using American Sign Language. American Sign Language is the most efficient sign language, because it’s a one hand language. European and Indian Sign Language is with two hands; you’re using both your hands to speak. So, I felt that. Especially, if you remember In Search of Vanished Blood, towards the end, the hand moves so fast, it’s almost like hysteria. The hand is portraying hysteria. This is what I do: Everywhere I create possibility; there is a way out. Let’s look at democracy.

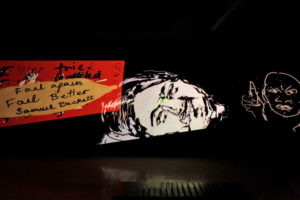

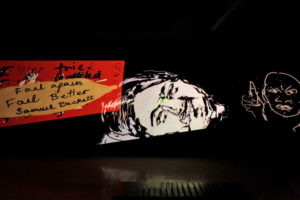

BL: That’s fantastic. Thinking about democracy, my thoughts turn to the tools that we all have and are all so engaged with, especially now because of COVID, when I wasn’t able to travel. I know you recently had a solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. You created a nine-channel installation with eighty-eight hand drawn iPad animations, an installation format that you call an “animation chamber.” I understand it was a highly successful format. The young British poet, Jay Bernard, reacted to your work with these words in The Guardian. He said, “It was this amazing room full of glitchy graphics. I looked the artist up and she was born in 1946. She talks about what it means to be engaging with the world, and certain kinds of liberatory politics. There’s something beautiful and powerful about the fact that she’s in her seventies, and is making this extremely fun, almost comic graphic art.” So Nalini I have to ask, what prompted this new step, which you also show on your Instagram feed?

NM: Well, you know, there was so much happening around me, especially politics. I had to express things. I’m obsessed with the moving image and I found a simple app that’s for twelve-year-olds. Using this app, I started to make animations. I also started to quote people like Noam Chomsky, Maya Angelou, and many artists and writers who I am very fond of and keep reading. I’ve carried their books around everywhere. So, my daughter who’s really savvy at these things, said, “Yeah, this is perfect for Instagram. Why don’t we open an account?” I’m not good at it, but she did it for me. Every now and again, if anything that happened, like if there was a horrific rape, I had to make a drawing and animate it. So that’s what I started to do, and eventually it became very huge. The numbers became huge.

One day my partner Johan said, “Let’s project this and see if it is robust enough.” I answered, “Well, yes, it does look pretty robust.” I then thought about the animation chamber, and got a chance to show the work in Bombay at the Goethe Institute as an animation chamber. At that time, I had sixty-six animations. I also composed the music for it, which was great. It was like I was a one-person show, and a one-person production company, which worked very well. The Goethe Institute had a lot of young people who came in and commented about the work. The students became very engaged with what I was talking about, engaged through the poetry. So, they were interested enough to checkup on, who is Maya Angelou? Who’s Toni Morrison? It got younger people like teenagers interested.

Then I said, “I’ve done what I think is important for young people,” and I continued. By the time COVID came and with it the lockdown, I made more animations and finally, it added up to eighty-eight. When the Whitechapel said, we’ll give you a commission for the old bibliotheca in the library. I said, “Yes, I’ll do it.” The library is a very interesting space, which I think was built about two centuries ago by a philanthropic couple who wanted to provide a free library for the Jewish immigrants, who came maybe from Poland because they had problems there. The people there were coming and settling into that area in the East End of London. Because people worked the full day, the library was open to 10:00 at night.

The curator asked me to make a work for such a space. She said, “Oh, it’s brick walls. Do you want us to clad the brick walls?” I said, “No, no. Let’s try projecting on the brick walls directly, because there’s history there.” There’s a long history, because today there are other migrants, Bangladeshi migrants living in the East End. The building is no longer a library, but still people do come. So, I kept the whole space intact, and we just projected on the brick walls, which really worked well. It had the feeling of graffiti, moving graffiti in an alley. And again, it connected to me to Heiner Mueller’s language, the language of graffiti. It was a good experience. And now I’ve started to make more animation chambers.

Image, courtesy the artist. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-1iK-IQNFfw&t=78s

BL: That’s terrific. It all relates to a line from a quote I love of yours, which I want to go a little deeper into. And that is, “The compendium of all culture is a lexicon for all artists.”

NM: Yes. Especially now more than any other time. Because of the internet, every artist in the world has all of the cultures right in front of her. There were days when we were combating the way Western artists were usurping African and Asian motives, and claiming them as their own. Whereas if the Eastern artist, the Asian artist, or the African artist did the same with the Western artist, it was considered to be, in a way, stealing. Today, one can’t say that, because Goya belongs to me as much as anybody else.

BL: Now, one little last question and it relates to something I’m asking each of my guests. You’ve already mentioned the ups and downs of the past eighteen months. My question is, how has technology affected you and your practice over the last year and a half?

NM: Well, I think that Zoom and Skype have been great portals for installing, and I think this is because we couldn’t travel anywhere. And the good thing was that at the other end, there were people listening very carefully, not only the curators, but the technical teams. As you know very well, video looks deceptively simple, but it’s not. It’s really not. It’s really like theater. You have to get everything right. You have to have your cues right, your colors right. That was well understood at the Whitechapel with a super team, and the same at the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, which now has a terrific director, Philippe Vergne, and in Malaga as well. In each and every place, we’ve connected through Skype and Zoom, with this great team at the other end, and us [myself and my partner Johan] looking through these lenses. So that’s one thing. Plus, the iPad animations continue. I create the simple drawings on the kitchen table, which I’ve been doing ever since we landed [due to COVID] in Amsterdam, where we have a small apartment. Johan has his own little workspace. I’ve just been working away, more to understand what’s happening around in the world.

BL: Thank you very, very much for your wonderful contribution to this conversation. You’re an amazing artist, and I have to say, you’re also a fantastic friend. Thank you.

NM: Thank you, Barbara. It’s been wonderful to speak with you.

—

Support for Barbara London Calling 2.0 is generously provided by the Kramlich Art Foundation.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

The series is produced by Ryan Leahey, with production assistant Vuk Vuković. Web design by Vivian Selbo. Special thanks to Lee Ranaldo for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded September 24, 2021; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Images

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uK9iRoPds8&t=91s

Image, courtesy the artist. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-1iK-IQNFfw&t=78s