[December 15, 2021 | Season 2, Ep. 4 | Barbara London Calling]

Barbara London: My guest today is Tracey Moffatt, a true innovator and an acclaimed artist who began her career as an experimental filmmaker. Born 1960, Tracey grew up in a suburb of Brisbane, Australia, where she absorbed a rich visual vocabulary by watching local television and movies. Her unflinching artwork is a mix of childhood memories, popular culture, history, film, television, literature and dreams. She uses fiction to comment on her own personal history and on serious issues of the volatile political landscape.

After receiving her BA from the Queensland College of Art in 1982, she photographed the Aboriginal Islander dance theater and became a founding member of the Boomalli Aboriginal artist collective in Sydney. In 1988, she sharpened her skills by working professionally in documentary production for television station SBS TV in Sydney, where she continues to live. Tracey, thank you so much for joining me.

Tracey Moffatt: Hello, Barbara London. I’m thrilled to be in a podcast. My first one.

BL: Well, you deserve this one and many more.

TM: Thank you.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: Tracey, you have such a rich and varied career. I want to start by saying that you’ve been so ahead of the curve from the get-go. I’m really happy to speak with you about your innovative and thought-provoking output. For forty years you’ve raised many questions of great relevance, ones that young artists in their 20s are asking today. I want to turn to how, at age 13, your directorial abilities took off with 8mm home movies and Instamatic photographs, which you made with your many siblings and cousins. Were you always keen on crafting narratives?

TM: Yes, indeed. I always played with camera, always for dress up and storytelling. Of course, I had a cast of characters, which were my huge family and the neighborhood children. I was the director. I was always the boss. I’d come up with all the storylines and would film my cast with a Super 8 camera. Back then, you would send the film away to be developed and it would be posted back to you. It was the same with still photographs; I always played with the little Instamatic camera. It was always the stage setups that I would create, making costumes out of blankets and towels and so forth, whatever I could find.

I say that this childhood play continues now. I’m still finding the cast of characters. Even yesterday, over at a film wardrobe place here in Sydney, I was looking for various costumes for a new shoot. It’s the same thing, but perhaps a little more sophisticated these days; I don’t use an Instamatic camera. I’ve never been one for realism. My interest has always been fiction and make believe—let’s use that.

I am able to use technologies, such as photography and film, to play with narrative. The so-called documentary or documenting or street photography has never been my shtick. That has never been my interest. I’m not about capturing; I’d rather construct. I want to construct it, construct my reality. I don’t want to be capturing reality.

I know my photo history, yet for me I’d rather construct the image than capture it. I want to make it up. I’ll control the lighting. I’ll play with the printing technique later on, and keep printing till it gives me the feeling that I want. I look for originality. I want to play with old printing processes—which I’ve done with photogravure and so forth—but using modern technology. I want the picture to look like it’s a hundred years old, but it came out of a digital printer. So I’m not that purist. I’ll use modern technology to create something that looks like it was made in 1910. I love that. That’s so exciting.

BL: Tracey, you and I met in the early ’90s. I was a young video-media curator. I was so taken by your film—I was taken by your energy and by how your work is so smart. It’s grounded of course in Australia, but also very deeply grounded in film history. So I’d love to know something about your interest in Maya Deren, who lived from 1917 to 1961. She’s the American artist who’s been called the mother of surrealist cinema. Deren’s background was in dance. I gather that her films, like yours, take viewers into the world of black and white dreams. What did you learn from Deren?

TM: Well, I did film studies at art school, where we studied the history of cinema. I’ve always been a big history buff, anyway. At art school in the very early 1980s, we studied surrealist filmmaking, watching such films as [Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel’s 1929] Un Chien Andalou. We studied Maya Deren’s [1943] Meshes of the Afternoon. I liked the imagery, the structure, and the intangible narrative. Her work never really was a straightforward narrative. She played with time past and present. It ticks back and forth, so you don’t know if it’s now or the future. That interests me. She played with structure. She was the real thing, the mother of surrealism.

BL: Your boldness just kept developing. Your dialogue-free film Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1990), a kind of world tragedy, tells the story of an Aboriginal woman forced to care for her aging mother. You were inspired by the 1955 Australian film Jedda, which captures a rare and honest glimpse into the heart of the history of indigenous Australia. What was behind this work?

TM: It’s a strange silent film, which is a mother and daughter story, and a little bit autobiographical, I guess: Indigenous daughter cares for her aging European mother in the middle of nowhere. But it’s shot on a sound stage. It’s very staged and almost technical to look at, shot in 35mm. We created sets for it. It is the “artificial” Outback, with piercing sound effects and so forth.

Was it influenced by Maya Deren? has a surrealist magic realism quality to it, and it doesn’t play with real-time. I remember storyboarding that film, drawing every single frame. I was inspired a lot by Hitchcock, because I had read that he loved to draw his films first. In fact, he found it more exciting. He preferred just to draw it, then he would go, “Oh, now I have to film it.”

BL: That’s terrific. Throughout my career, I’ve always kept my ear to the ground, interested in what artists were doing. It didn’t matter to me where an artist came from. I didn’t care what race, gender or age they were. Bottom line, I was interested in great work. I had heard about you, so when Debra Zimmerman from Women Make Movies called and asked if she and you could come so we could preview your film Night Cries, I thought, well, that’s a great opportunity to see Tracey’s work and meet her. From then on, I was a great fan of your work. I’ve tried to see every show of yours that I could. And that’s how it all began. I was so happy when you lived in New York, because it meant we could connect in person more easily.

TM: I remember that. I had a 35mm print, s0 we needed a 35mm projector. You allowed Debra Zimmerman and I, from Women Make Movies, to come in and use the teeny theaterette at MoMA. Do you remember that little theaterette?

BL: It’s still there.

TM: Yes! It was hard to get a 35mm projector, so you were very generous. When we met, you were quiet and didn’t say much. But then over the next 30 years I would see you here and there. You were at everything; you were always everywhere, Barbara. And you’d always wave hello to me, so that’s been nice.

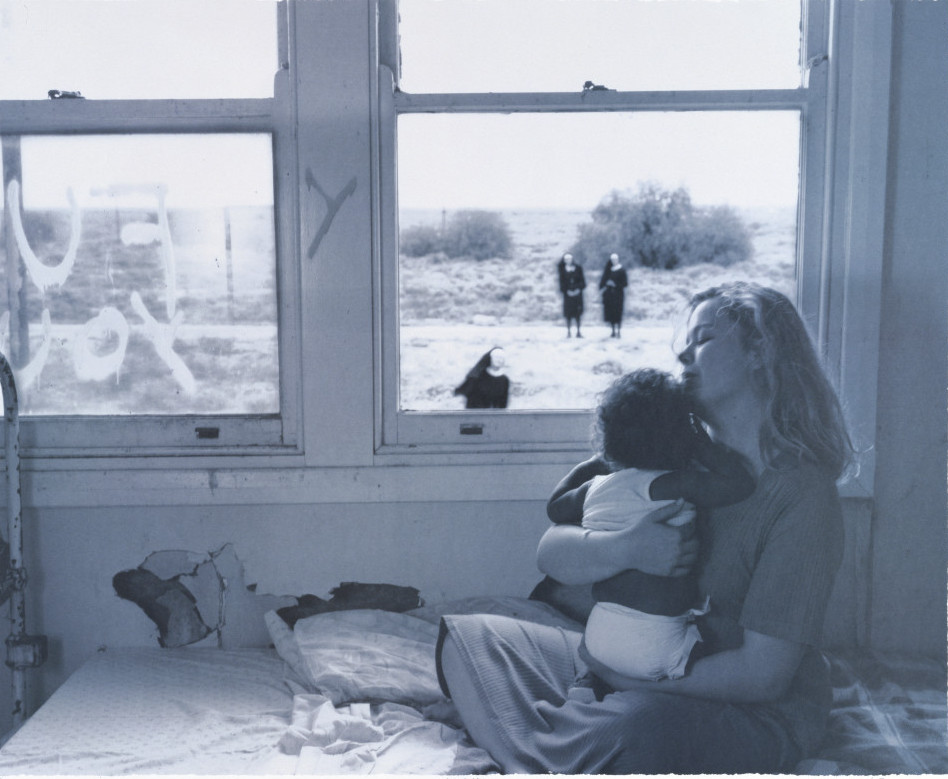

BL: I have always been a sponge for information. I’ve been fascinated by how you create your own version of reality, and by how you work between the mediums of film and photography. Each of your photographic works is visually stunning, and each appears to be a film that, to quote you, was never made. The Something More series (1989) series is composed of six really rich Cibachrome prints, three in color and three black-and-white. Each print borrows from film language. Together they construct what could be described as an enigmatic narrative of a young woman looking for more out of life than the circumstances of her violent rural upbringing. You’ve said that the photograph is a story not quite told. What do you mean by that?

TM: I knew that with the medium of photography, you could go so many places with it. I was always interested in artifice and construction of the image, to make it and to fake it, rather than to capture. I’m creating my own reality. I’m not out there doing street photography. I prefer the stage and heightened color—everything heightened. For example, the saturated colors of the Something More (1989) series came about purely from that. In those days, there was only the 4×5 format. If you wanted your images to be very striking and rich, you went with the 4×5 camera, which now no one can use. It’s all digital.

The format gives that very rich organic look; I was very lucky to have that. I almost tried to animate it. I played with moving the camera at the same time, so it was somewhere between still and moving. But I did study photography formally, and was always interested in breaking the rules. To this day I still can’t use a light meter. I never could do the technical stuff. When I used to shoot this type of work, I would direct it, so I wasn’t physically handling the camera a lot of the time. Sometimes I do, and I shoot myself. When it’s a photo shoot, often I have a camera operator and I work with wardrobe and production people. It’s quite a production.

BL: It’s just like during your childhood?

TM: Exactly, yes.

BL: Let’s now talk about how you’ve always faced head-on very serious topics, many which are still very relevant today. Your work Nice Colored Girls (1987) tells the story of three young Aboriginal women, who “cruise” Sydney’s King Cross entertainment district looking for fun. A group of very drunken white man go after them. How did you handle such a serious topic back in 1987?

TM: I was reflecting the world I saw around me, and again I played with time. I included historical texts in that work, too. Some of the first journals that were written by Captain Cook and his men in Australia [in the 18th century] responding to the dark maidens by the harbor shore. The maidens would basically roll them, rip them off, steal from them and run away. I talk about it—it’s still happening. The same thing is going on, the crafty dark maiden surviving.

Nice Colored Girls was funny as well. That was my first short film. Was it well received? I think so. Some people were offended. Oh, well.

BL: Let’s move on to a very different form of yours, although one still very much grounded in movies. Around the time that movies, transferred to consumer-level VHS cassettes, were inexpensive to rent from video stores, you appear to have obtained a really big library of old Hollywood classics on VHS. Then you made some remarkable archival works.

This particular series of work is serious. And they’re very you, because they have a clever touch of humor. For example, Lip (1999) includes clips of black servants talking back to their bosses in Hollywood films. What were you trying to say about mainstream cinema through them? And how do you think that conversation about television and cinema and different video platforms continues today?

TM: To begin with, I do have an editor that I make the montages with, Gary Hillberg. He’s a genius. And he has a collection of 2,000 films on tape. We put our heads together. I would come up with the scripts. Back then we worked together about 13,000 miles apart—he was in Melbourne and I was in New York. We never were in the same room. We put the works together by going back and forth. He would post me edited versions on VHS and so forth. Lip was the first one we did.

The topics were the dark servant in cinema, the stereotype. I chose clips where the women were powerful. We were subverting the so-called image of the victim and turning them into something powerful. I think the character of Hattie McDaniel as Mammy in Gone with the Wind (1939) rules the roost. Mammy’s the boss; she’s telling Scarlett O’Hara what to do. I claim that the actresses were scene stealers. The dark maid, you never forgot them. In the little moments they had on screen, they made it work. There’s the great scene from Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) with that grumpy maid, who’s telling Katharine Hepburn what to do, and so forth.

On another personal note, my mother worked as a maid for a doctor. She also worked as a cook in fancy private boys’ schools, in colleges, and so on. Again, it resonates in a personal way for me. I explored many themes in those montages. I did one called Other (2010), which is a sexy back and forth gaze between dark and white people just looking at each other. It builds up to this climax with a volcano exploding at the end. It’s really sexy.

TM: Mother (2009) and Revolution (2008) was another one I did, where it was just scenes of revolution depicted in cinema. The buildup of the peasants outside the window and the nervous aristocrats inside the mansion, finally erupting into revolution. I won’t give the plot away. I made eight in all, and they have been fun to put together. The last one we did was in 2015, and has actually been touring around Australia to all of the regional galleries. That series of works of montages is called The Full Cut (1999-2015).

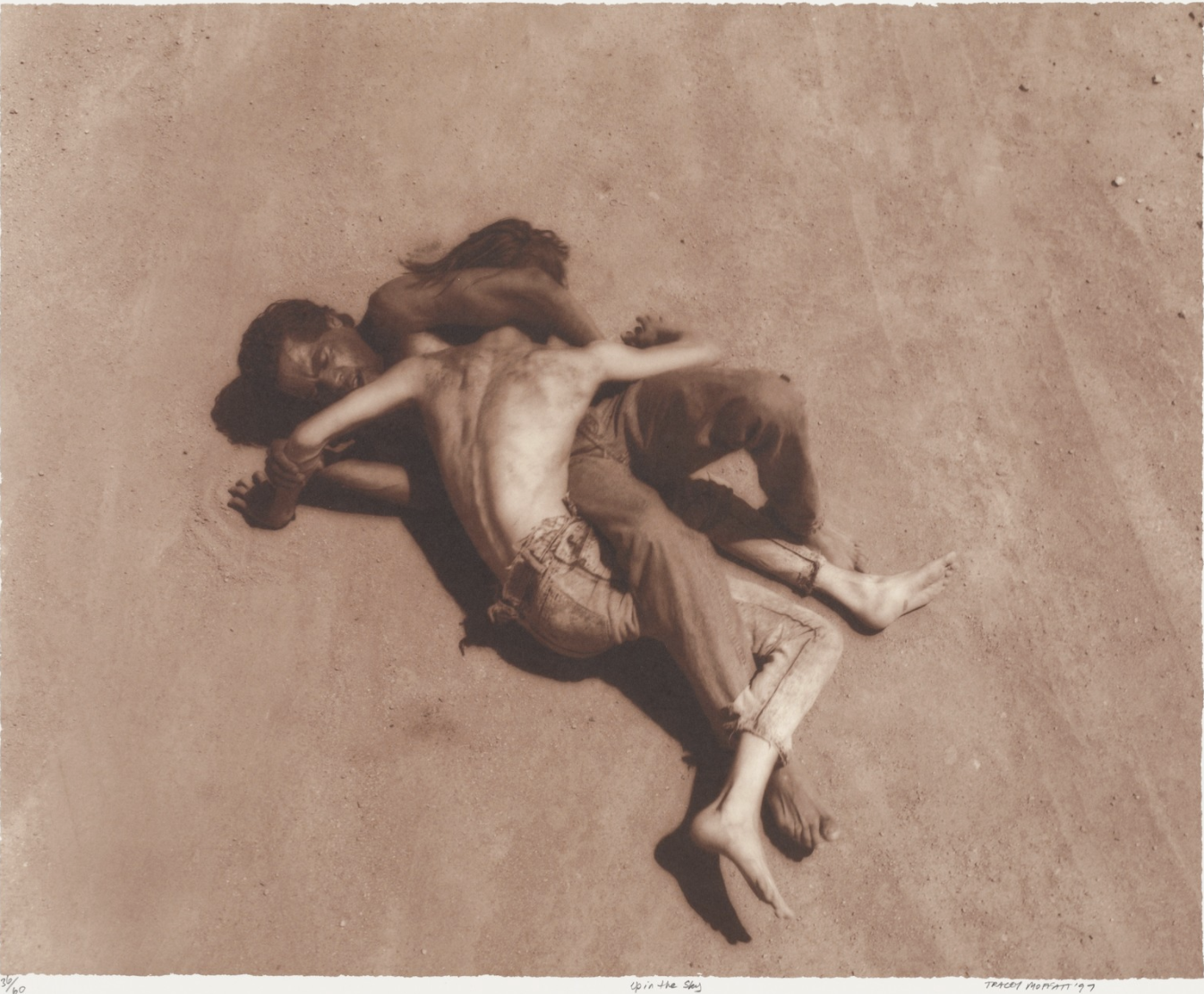

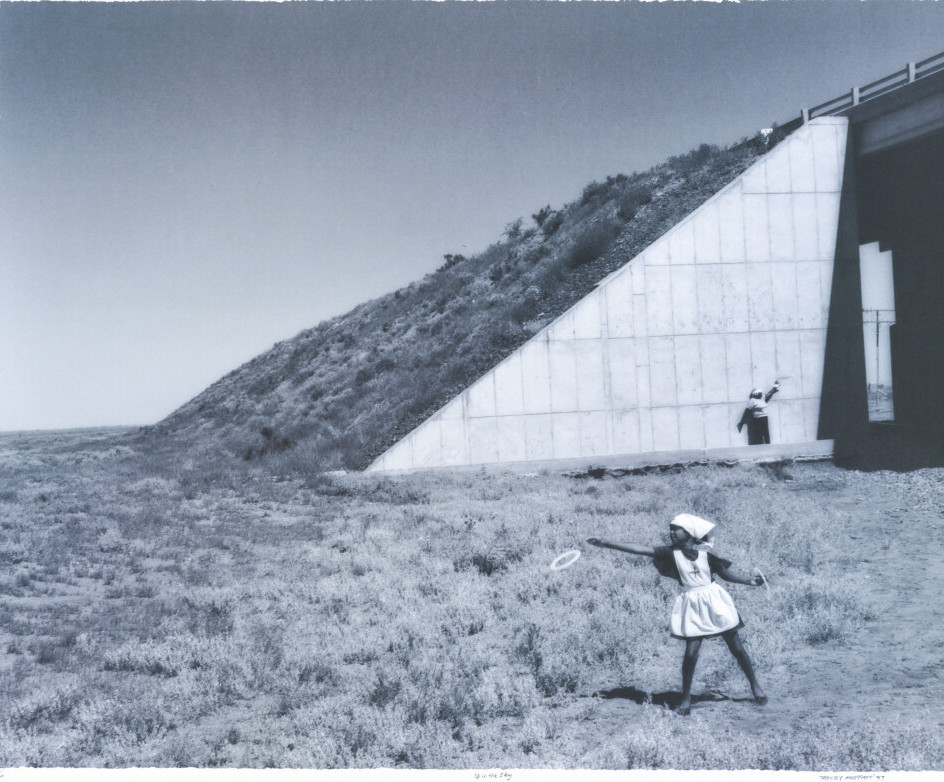

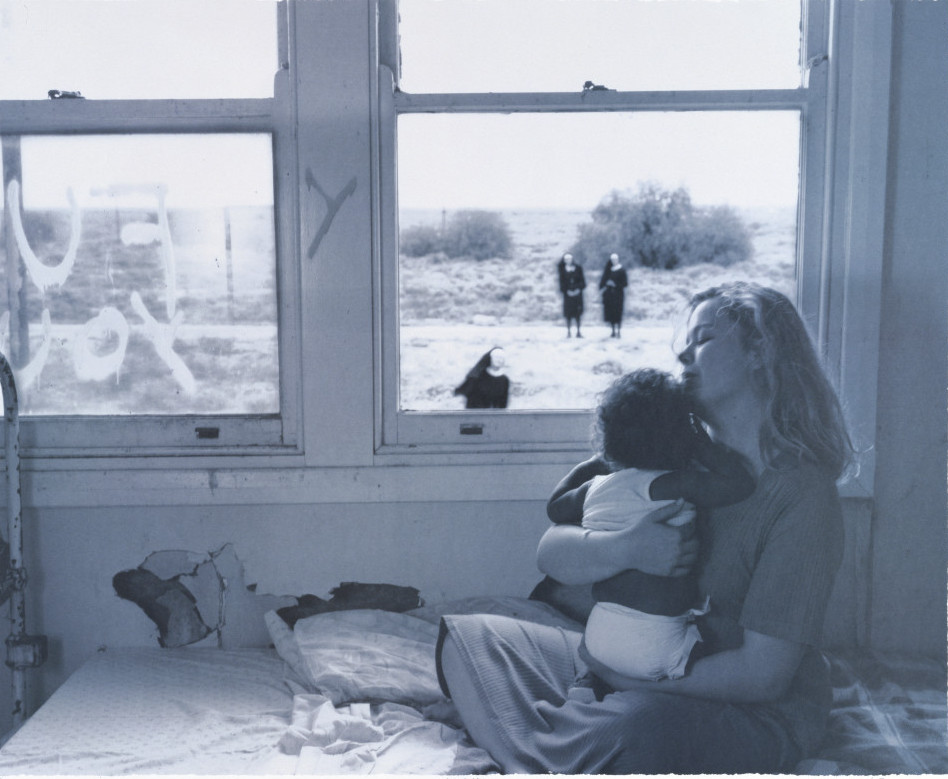

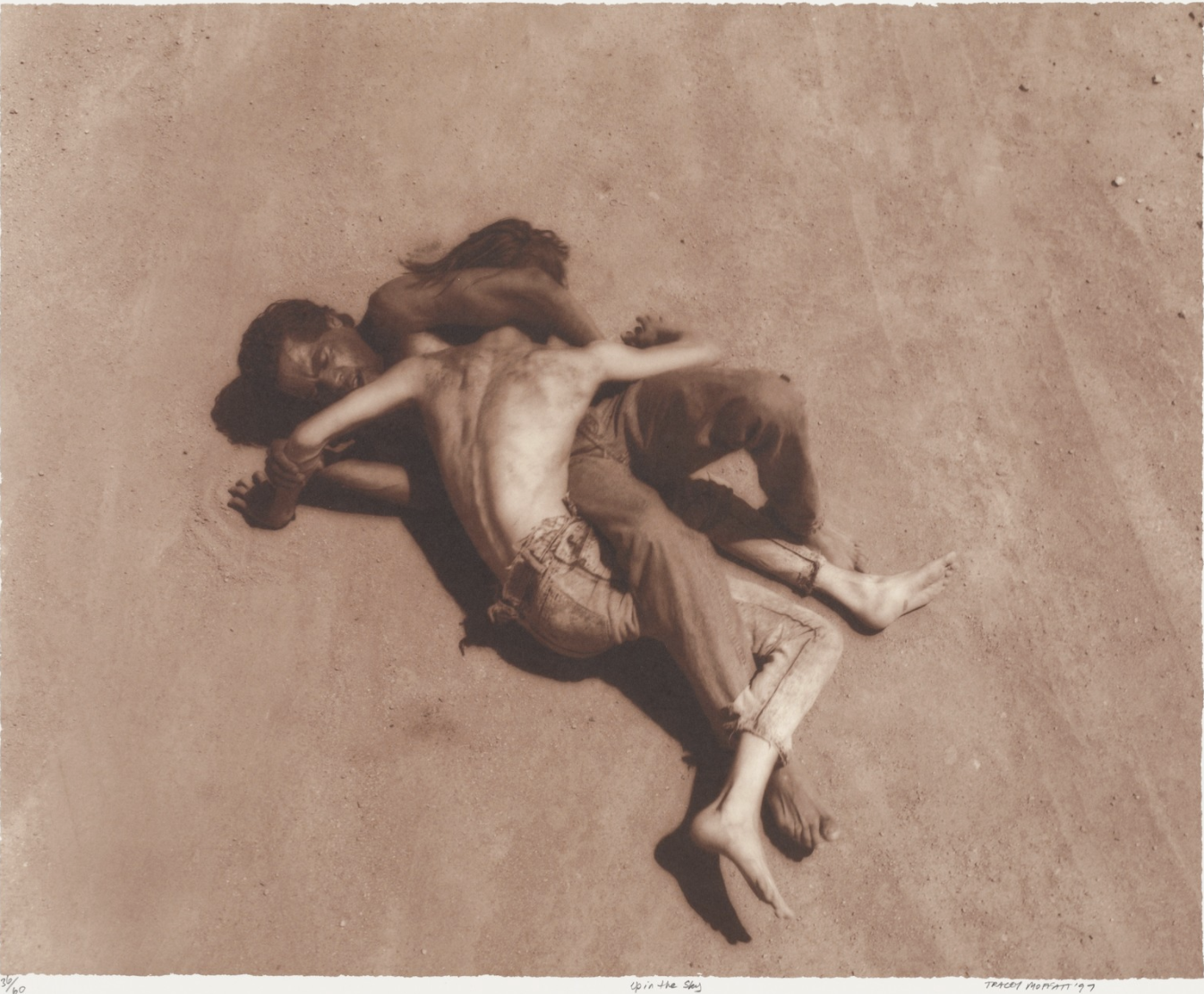

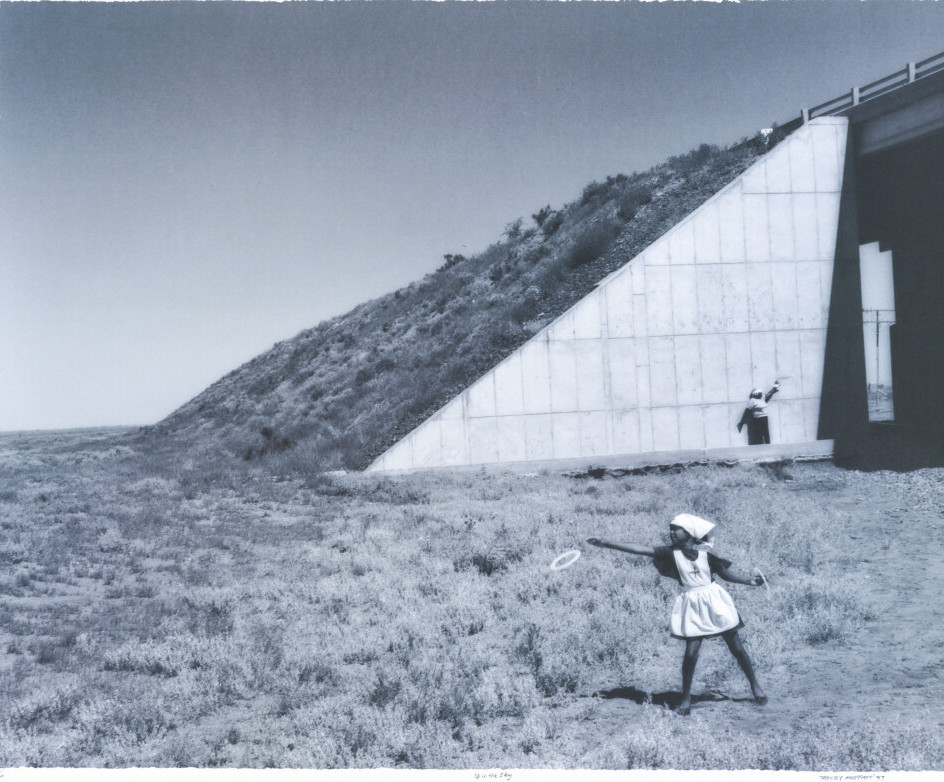

BL: Let’s move on to 1998, when you had an exhibition with the title “Free Falling.” Organized by Lynn Cook at DIA, the show took place right at the moment the art world held staged photography in its clutches. I think the artists Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall, Gregory Crewdson, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia, like you, turned photography into high art. For “Free Falling,” DIA commissioned you to make two new works. You shot a suite of 25 photographs entitled Up in The Sky (1997), near Broken Hill in the Outback. You drew upon images of a landscape that has been central to Australian mythos for a long time.

You were 15 years ahead of other artists, in that you were exploring the narrative boundaries of photography, as well as its relationship to cinema.

DIA also commissioned a video installation, your first in that medium. For the installation, I love how you returned to the subject of the surfer, a figure you had used earlier. The surfer is a figure close to the heart of Australia’s contemporary self-image, given all of the country’s beaches. I want to know: How do you keep a balance as you ride your own wave between Australian and global culture?

TM: I don’t think my work is about Australia. To use a cliche, it has a universal appeal. The images in the Up in The Sky series, commissioned for the big show I had at DIA, were all shot in the Australian Outback. Yet they were read in a different way by Americans. Some thought it was Texas, some Israeli people thought it was Israel. It’s a nowhere sort of space, a wasteland inhabited by a cast of characters.

Of course, one of my biggest influences is Southern literature. I’ve always loved Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote and of course the great Carson McCullers, who I adore and who wrote books and stories. I loved her Ballad of the Sad Café, Clock with No Hands, Reflections in the Golden Eye, all fantastic. I come from the north of Australia, which is considered the deep north—sort of backward. I came out of that. Racism, larger-than-life characters, the tropical heat—really this is where I come from, a tropical upbringing. That’s why the South resonates with me, especially when I read Southern gothic novels.

A little of that probably appears in Up in The Sky, in the compositions, the storylines, the small-town shenanigans, and so forth. When you say, how do I resolve it? I don’t bother with it. I don’t like to close off readings of my work and say, “Oh, this is about Australia.” I often make the work here, but it doesn’t mean that it has to be read that way. You don’t need to know the history of Australia, or have even been here. I think that might explain why my work has traveled. It’s traveled, it’s shown internationally, and it has crossed borders. At the moment Up in the Sky is showing at the Tate Modern in a show [“A Year in Art: Australia 1992”], and I’m delighted. The Tate acquired the work about 20 years ago when I had the DIA show, and finally it’s on their wall.

TM: Then the video Heaven (1997) portrays surfer guys stripping. It was really shot like an ethnographic film, in observing the ritual of guys stripping out of their wetsuits. It’s completely voyeuristic and very funny. I shot some of it myself. But then I paid some young women 200 bucks to walk down along the various beaches in Australia, and film the guys coming out of the surf and stripping out of their wetsuits in the car parks. It’s a very funny video, one of my most famous pieces. People say, “Oh, I was in Japan and I saw that funny video you made with the guys stripping.” It’s the trashiest thing I’ve ever done, and almost the most famous thing. It’s funny.

BL: It’s very funny. You were in New York in 1998 around that time you had the DIA show. You lived in Manhattan for about fifteen years, but in 2010 you moved back to Australia. It was in 2012 that you and I met in Sydney for cocktails at a beautiful restaurant, overlooking Bondi Beach. At the time you were getting very busy with your exhibition, “My Horizon,” which was scheduled to premiere in the Australian pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. I’m so fortunate that I happened to be in Venice for your opening. I have to say that you came up with a really ingenious use of the brand-new building.

To me, the show was so brilliantly you. You imbued the work with Australian culture, cinema history and your personal history. You created four outstanding new works: two videos, The White Ghost Sailed In (2017), rich with history itself, and Vigil (2017); and two series of photographs, Body Remembers (2017) and Passage (2017). It was impressive how you installed your large photographic works unframed, very high up on the walls around the gallery, almost as if an ancient freeze. You also said you wanted those photo works to feel as if they’d come out of the earth and were hit by the sun.

TM: That’s true.

BL: I’m curious when you prepare such a massive show with new work, how do you put it all together? It’s a monumental task.

TM: Over a period of time it comes together. A lot of test-printing those big images. The title of the show for Venice was “My Horizon.” I’ll just read what I wrote:

“‘My Horizon’ can be about wanting to see beyond where one is. It can mean to have vision. It can mean to project out and exist in the realm of one’s imagination. This is what artists do. This is what I do and it is what saves me….”

“My characters possibly dream of escape, or they’re weighed down by their memories or their histories…. ‘My Horizon’ can describe reaching one’s limitation or wanting to go beyond one’s limitations. It can be likened to a dream state, like when one looks out and beyond where one is.”

“The horizon line can represent the far and distant future or the unobtainable. There are times in life when we all can see what is coming over the horizon. And this is when we make a move or we do nothing and just wait for whatever it is to arrive.”

I don’t like to read usually, but I thought might as well read from my book, the catalog from the Venice Biennale. That was a lot of work, the Venice Biennale show.

In terms of the themes in the show, I dealt a lot with with news footage of asylum seekers, wrecked boats and people drowning, interspersed with movie star faces in shock—Elizabeth Taylor going crazy, as if watching these boats sink, that juxtaposition. The idea of seeing beyond the horizon, it’s what those people did before they got on a boat, to look across the sea to another place, to see beyond the horizon, to go somewhere. It took a lot of guts—it takes a lot of guts to leave one’s homeland, to try and see beyond.

There was that series Passage, which was a very high-colored film noir series of images set around the docklands. I had another cast of characters, mainly African-looking. I wanted the work to have an exotic location, like Nairobi or even New Orleans, so I’d take it out of Australia—let it read as somewhere else.

The narrative is set around this young girl. She might be a stowaway about to get onto a boat, leaving her baby. She gives up her baby. I shot it through fog, I had this fog machine, so a lot of the faces of the characters were in shadow or masked in fog, which gave an eerie reading to the work.

Again, that was just staging the works. I shot around a dockland area in Western Australia—but I don’t like to reveal often where I make my works, because then a lot of critics tend to turn my works into a document. “Oh, Tracey Moffatt documented the docks.” No, I found the docks and I made up a story. They were just a backdrop. The images are not about those docks. The images are coming out of my weird brain. That’s where they come from.

BL: I love your weird brain, because you really come out with very strong work.

TM: Barbara, I couldn’t believe you came to Venice. It was so great to see you and Barbara Hoffman at the party in the fancy cloisters. All drinking Bellinis. [Laughs]

BL: Let’s move on now, in closing, to your very new work. You have an installation of light and sound that’s set in an abandoned farmhouse on the flat western plains, a six-hour drive from Sydney. It’s seen largely by truckers driving by. The house will pulse red light and the sound will be heard coming from inside the house and from the surrounding grassy area. You’ve told me that the installation is the type of memorial flame that acknowledges indigenous people, and that you will try to keep this installation active until COVID disappears off the face of the earth. Tell me a little something about this new work.

TM: This piece I’m creating is called A Haunting (2021), which is set in a dark farmhouse by the side of the road, along a highway that’s a six-hour drive from Sydney. The farmer has allowed me to create this piece, where I’m going to be lighting the house up with this eerie red glow. It’s in the middle of nowhere and hardly anyone will see it, except passing truck drivers at night.

It could be read in many ways: It’s a sort of tribute to the indigenous groups of that area. There was quite a dark bloody history from that region, where there was a colonial settlement and then indigenous skirmishes. An ancient stone ax head was found in the grass near the house by the farmer. He allowed me to hold it. It was amazing to hold in my hand—its solidity felt unbroken forever as I grasped it.

I want this house to stay lit like an eternal flame, and have it run hopefully for infinity, if I can keep it going. But also, the work is welcoming like a lighthouse in the middle of this dark, grassy sea—a sort of welcoming, familiar thing that I think we are looking for today in this global pandemic that’s happening, when I think all of us are feeling a little unhinged and looking for reassurance and guidance.

I’m claiming now that I want to keep this alight until COVID disappears. That’s my plan, an eternal flame. People won’t read it that way—that’ll be what’s fascinating. It looks like it could read as an ambulance or a police light or a forensic crime scene, or a photographer inside the house photographing a crime scene. I’ve also said that it could sit like an agitated photo darkroom from a distance, or even a lonesome bordello in the middle of nowhere.

And also, no one will see it. It’s going to be in the middle of nowhere, but that’s the appeal for me. No one’s going to see it, but you’ll know about it. How many of us have seen [Robert Smithson’s 1970 earthwork] Spiral Jetty, on the salt lakes of Utah? I’ve never seen James Turrell’s Roden Crater.

BL: The works you mention are hard to get to. Yours is hard to get to, too!

TM: It’s a six-hour drive; who will go?

BL: I think pilgrims will go to see your work. Curators like me will want to go see it.

TM: I hope so. Nearby, there’s an award-winning country pub that wins awards for gourmet lunches.

BL: This brings us to my last question, which I’m asking each of my guests, and it has to do with the ups and downs of the last 18 months and the struggles we’ve all faced in trying to adapt. How has technology affected you and your practice?

TM: I’ve seen lockdown time as nothing but valuable time to get on with some new work and to put my head around new ideas. The isolation is forced on us—good. It means reading time and, boy, have I been reading. I’ve been reading so much. One of my greatest loves is to read. There’s nothing to complain about. We’ve got all this time in the world. I say, let’s just get busy and stop going insane and put our heads around creative shenanigans.

BL: That’s beautiful. I think you’re fantastic and I can’t wait to see the new work and everything else beyond it. Thank you so much, Tracey.

TM: Thank you, Barbara.

—

Support for Barbara London Calling 2.0 is generously provided by the Kramlich Art Foundation.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

The series is produced by Ryan Leahey, with production assistant Vuk Vuković. Web design by Vivian Selbo. Special thanks to Lee Ranaldo for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded October 1, 2021; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Images & Video