[December 1, 2021 | Season 2, Ep. 2 | Barbara London Calling]

Barbara London: Today my guest is the software-savvy artist Jakob Kudsk Steensen. Born 1987, now based in Berlin, Jakob grew up in Denmark. His mother was an educational sociologist and his father was an engineer. A tinkerer since childhood, Jakob’s interest in technology developed after he hacked a video game called Unreal, using Level Editor to do so. He still works with this same tool, which is now known as Unreal Engine. Jakob, thank you so much for joining me.

Jakob Kudsk Steensen: Thank you, Barbara. It’s always a pleasure to speak with you and hear your thoughts.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: I want to start somewhere near the beginning, because it sounds like you’ve always been something of a geek. As a graduate student in London, at Central St. Martin’s College of Art and Design, you were making observational drawings in nature, but then you became obsessed with the art department’s new high end 3D scanner. I find it wonderful that onto the scanner, you plopped a live crab and developed animated imaging of it. What was your fascination with technology and why did you find yourself transitioning away from traditional visual art?

JKS: When I was growing up, these interactive 3D technologies were becoming quite common. But at the same time, I grew up a bit in Copenhagen, in different countries, but also in the countryside in a town of 500 people by the coast. I’m of a generation that really grew up right in the middle of all these new, massive, more industrialized, very easy to use and approachable tools for making virtual worlds. At the same time, I was going to this Rudolf Steiner school, where you’re outdoors a lot during school. I really grew up in the middle of it all. As a kid, I wanted to be a professional animator, which primarily came from comics. I was really obsessed with drawing. That’s something I’ve been doing since about 4 years old. But then video games came along and it was like a new form of really imaginative animation.

Alongside of this came the tools to make video games, which became open source. So you were no longer just a consumer of what you’re experiencing. You’re a kid sitting in the countryside, and you’re no longer just consuming something and buying it, but you can participate in the creation of it. Then the Internet came along and I began modifying the games. To do so, I used the level editor of the game, which is the world you’re in within these 3D video games. I started being part of communities that were modifying the worlds that you were experiencing, and then was sharing them online with other people and sort of creating forums and things. Actually, some of the people that participated then are professional creators today and are using video game technologies for music videos, for example. It’s been interesting to see this transition from just growing up with these mediums as a kid, and moving towards being a professional using the tools.

At Central Saint Martins, I was primarily focused on these very scientific drawings of specimens in natural history museums, like the Gordon Museum of Pathology in London, where I was doing a lot of drawings. I did these big paintings of chameleons and of stuff in jars. Then one day we were given a tour of the new 3D scanner at Central Saint Martins. It was really expensive to use. I couldn’t really afford to create artwork with it, but I talked to the director of the lab and he was like, “Just come by and we’ll do these experiments with dead animals.” So, one day I biked to the harbor in London at 4:00 a.m. I’d talk to the fishermen to hear what they’d caught. They saved one of these invasive crabs, which are pretty big. Then I biked up in the morning and bought one from them frozen and biked back to Saint Martins before it defrosted.

I went to the working lab and put it in the scanner for seven hours. When I went back, the 3D image was this fascinating object that I felt I could relate to. So you could call me a geek, in a way, but really, I think I’ve just grown up in a generation that feels this rift between the more classic and the new. Playing with the 3D scanner, doing observational drawing at the same time and working with dead animals—it felt like I was exploring this rift of existence with the physical, the virtual and ideas of decay taking new forms. It became my practice since then. I think I’m exploring this rift in existence in a way. I’m born in a generation of artists that work between the more traditional mediums and the new virtual tools. I think if someone were just seven years younger than me, they’re fully growing up with all of these virtual tools. But I really felt the transition from not having access to the tools to having full access to them. That’s why at Saint Martins, I started working with the 3D scanner and scanning dead animals, whereas before I was just drawing them. But at the same time, I was also drawing them, because it felt to me that it’s kind of exploring the reality I am part of. I grew up through this transition, so that somehow makes me feel that I’m exploring what it means to exist in both the digital and physical realm at the same time.

BL: Your early years are fascinating. I know that after you completed your MA and your MFA, you jumped right into VR and video game production. Video games are really complex, multifaceted narratives, which require such specialized expertise. Production relies on teams of artists and engineers, who spend months and months developing each new project. I see you as an easygoing person. It seems to me that you’re very well suited to the teamwork that’s required in a software propelled industry. I’m curious, what was your role in this collaborative environment? I’m also curious, what did you take away and adapt from it to your own work that became very intricate narratives?

JKS: There are two things that I was working with before. For one, someone would get in touch, and they’d have a story, a design and idea, then they’d contact me with it. But sometimes it was as literal as a PDF or a document that said: “This is a one-hour experience, and after five minutes, this feeling and this thing should happen.” They’d write it out in a very linear sense. Then my job would be to think: OK, how can I convert these ideas and stories into emotional, colorful, 3D worlds, where you take a narrative concept, but you transform it into something non-narrative. That was my job then, to build a team around me to create that. This team would often be, especially in virtual reality, in New York. Around 2015, it was really exciting to be there, because suddenly you were working with a stage designer, a composer, with an educator in tech, a game developer, and someone in film.

It really took this moment of creative burst of activity that was very present in New York from 2015 to 2017, when VR really came forward in this second wave of VR that we’ve just been through. It really felt invigorating to collaborate with people from many different fields that way. For me as an artist, I think that fits my personality. I like to enter a wilderness, in a sense of bewilderment, and a sense of chaos navigating through it. That’s something too, working with these digital tools. Once you start working with a lot of people, when you let go of control, you don’t really know what world you’re going to build. It will happen through how you talk to other artists as you collaborate with them. How do they feel as part of the project? How do you foster collaboration?

How do you make an animator work in VR/the virtual, who’s used to making video games, suddenly work with a dancer? How can they work and talk together? That’s like a lot of feeling and transformation at stake. Professionally speaking, I went from producing very structured and logical work. Then I sought to rebuild the sense of collaboration and the scale of the work. For my new work, we are a team between five and ten making a project now. I went from creating teams to create work for someone else, to then just being restarting in a way. In my studio in the basement at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City, it would just be me alone. I had to be alone, because I had to rebuild my portfolio for my practice and navigate a new network, which is more like the art world.

Then slowly I started to add people into the projects again, so that I could start working. I knew how to do it before, commercially, but in a new way, in a more chaotic sense, where I never really know what the final virtual world would be. In the industry, you don’t create anything unless you’re very certain of what you want to make, because it’s so expensive and elaborate. But I know the tools so well now that I can kind of jam. It’s almost like setting up jam sessions and parameters to work with other artists. That’s why I jumped right into it and made it my art practice.

BL: That’s great, you’re a VR jammer. I was very excited in 2018, when I visited you in your hi-tech studio in Jersey City at Mana Contemporary. There you were, surrounded by a lot of plants, and I understood that this natural environment meant a lot to you. I put on the VR goggles and experienced what you were up to. Within a very short time of that meeting, we both traveled to attend a festival in Manizales, Colombia, which happens to be very beautiful, very mountainous. At the festival you presented your installation, Pando Endo (2017)

I was impressed. We were staying at the same hotel, having breakfast and dinner together at the hotel.

Early one morning you weren’t at breakfast, because you and Liz, your wife, associate producer, had gone off to visit a forest at the edge of the Nevado del Ruiz mountain. When you returned, you were very muddy because it had been very rainy and had skidded down the hills. But you were very excited about the sounds of birds and images of plants that you were able to capture. I believe those audiovisual images became part of your next VR work, RE-ANIMATED (2018-2019), the installation featured in the Future Generation Art show during the Venice Biennial in a beautiful Palazzo.

I’d like to know about your methodology, which we haven’t really talked about before. It seems that your methodology is analogous to field recording, what sound artists have done. You go and spend weeks and months outdoors in some of these very remote landscapes. You capture the sense of that space and place by closely observing the tiniest details of what nature is doing, how it unfolds right before your eyes and your ears. You so beautifully use natural sound to reveal how static-seeming situations are just bursting with life. I’d love to know a little bit more about the process of how you use sophisticated software to build upon what you observe in nature. And, what is the larger connection you try to make between reality and virtual reality?

JKS: There are a few different reasons I’m on this journey to create these projects like that. One is just that, in growing up with so much technology, I feel like it’s becoming a world where we think we can control and design everything. But the rules of life and the planet don’t really work that way. That’s why I’m fusing this process of 3D scanning and of field recording. We can now scan small fungi roots under the ground, or record the sound of insect wings fluttering. These technologies can augment your senses as a human, so that you can see hear and experience things that are normally beyond your human sensory system as a naked body. You can augment this, which is one reason I’m doing it. And I think artists have been doing this for a long time.

Artists have been doing field recording with microphones since the sixties or the seventies, and better than I do. There’s a long tradition of that. But what I try to add is this sense of wonderment of the natural world, and point to what life can be, beyond the tools that we are surrounding ourselves with. I like to think that I’m re-wilding, creating kind of wilderness in the virtual, by not knowing what I create before I go to a landscape. I have to follow the rhythm of a season of whatever I encounter over a long period of time in a landscape, or whatever I learn to look at by talking to a field biologist. They might see something that my eye cannot see, due to the way I look at things. But someone who has spent thirty years of their life in one specific landscape, they can conjure a perspective on a place that you and I really can’t.

You have to have been there to read the signs of the world that way. I’m increasingly becoming fascinated by reading these signs and going beneath what I think I know about a place, and then just creating these virtual worlds by doing that, in practice. It means, I don’t know what a work is anymore, until I just go through a landscape. That’s also an emotional reminder for me that life can take any form beyond what you think is possible. We are so structured and rigid today, with calendars, with the way we work and live. It’s like things are so contained, but the planet and evolution is so wild. I like to think of myself as someone who is infusing this very controlled world of technology with something from these environments that is wild and unpredictable, and very slow and very emotional.

I’ve been rethinking why I’m doing all of these things. We used to talk a lot about specific natural history and technology. But increasingly I think it’s more about emotional presence and a psychological response to an environment, where when the exterior world is changing, you’re changing inside of yourself. With new change inside of yourself, you can also change the world. In terms of climate change and transforming landscapes, I think this is what I’m doing. As I’m moving through a landscape, it’s like I’m sensing, feeling, thinking, using technology to create imprints from that place as I move through it. These little imprints are what I collage together and present to people. But they’re also psychological moments or feelings of transformation.

I’m starting to learn as an artist, that’s actually what I’m doing in these works like RE-ANIMATED that was at the Venice Biennial. It’s about an extinct bird. There’s a memory of it, because we can hear a sound recording of this extinct bird’s song. But it’s very emotional; it’s like an experience of transformation. I’m actually rethinking my own language about what I do from natural history and technology, to do something about psychosis or your mental space becoming the landscape you’re moving through. These are very new ideas for me, but is actually how I’m starting to think.

BL: That’s wonderful. As you’ve been talking about you being in the landscape, or you thinking about the change in you and the change to the landscape, I want to go into how you’ve described sound as the animator of the visitor’s physical journey through your work. Do you want to say something about that?

JKS: Animation and animism have been key themes for me. Bringing life to things you think are dead, but you know through science are alive. The soil is alive. When you look, it doesn’t seem alive, but it definitely is. You can animate, make the soil come alive. For many years sound has been a key theme for me, because I grew up with all of these virtual tools. I know how to paint very academically, and I know how to create images. Our digital culture is so defined by images. But sound is very spatial and the virtual is spatial. The virtual is not a surface. This is something we have invented; we invented how the digital is experienced through a flat screen. But the virtual is a coordinate system that can track movement and sound scale and transformation.

That’s what the virtual can do. It’s much more than just a flat surface. Sound has been something that I’ve been trying to push through multiple works to explore the kind of invisible space that’s actually quite tangible, when you work with technology. When you work with sound or are recording an insect moving through space, you’re also working with time. You can slow down the insect’s wings or the way it communicates. You can hear things you normally can’t as a human, but digitally, you can also move things around in space. Virtually, because it’s sound and so physical, you can also present sound as mass, as an invisible experiential mass, where a screen will always remain in front of you. It’s also like light that hits your retina; and light exists through the particles in the air, between you and what you’re looking at.

Sound can really “whoosh” and move around you. So, I’ve been using sound to provoke movement in people. It’s not just the visual that is maybe making people turn around in a virtual reality work or in a video installation. The sound can move around and up and down, and kind of surprise you from different angles. It can occupy a lot of this invisible space that a lot of other means of presenting what the virtual is, cannot. The screen will always been in front of you, but sound is an invisible mass. I’ve been fascinated by making instruments in the virtual space, from sounds from different landscapes.

BL: I just wrote about your work for the catalog for your Berlin show. I really thought about what you were doing, and about how you have the same tenacity and dedication to detail, and to the metaphysical as a few earlier artists have, one being Bill Viola. And I thought about the 19th century artist, Caspar David Friedrich, and how he, Viola and you, have assiduously studied nature’s cycles of life. You have a keen eye on how turmoil, death and rebirth are fused with beauty, and view the landscape with its grandeur. There’s the emotional solitude, too.

Maybe we’ll talk quickly about Liminal Lands, which you presented at Luma in Arles in of 2021.

I’m so sorry I didn’t see it. You designed the work for four people. And you have described Liminal Lands as a transitional zone, where fundamental energies of sun, wind, water and bacteria connect to participants’ bodies in VR. Through interactive multiplayer technology, physical movement, spatial sound and textures synchronize altogether into “a musical composition driven by the immersed participants.” Do you want to just talk a little bit about how you get the viewer to experience content and narrative, rather than all of this gear and software that other people focus on?

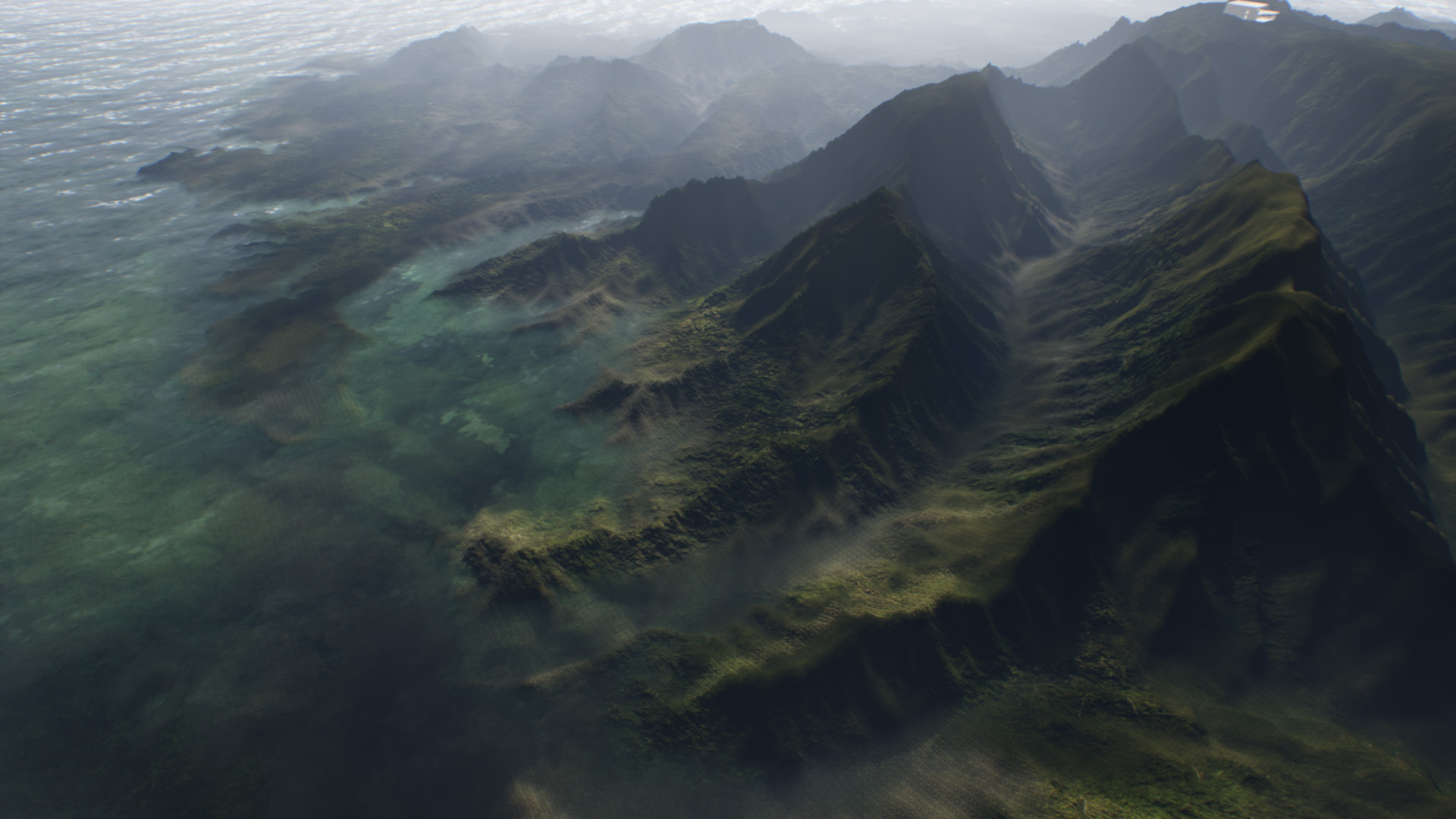

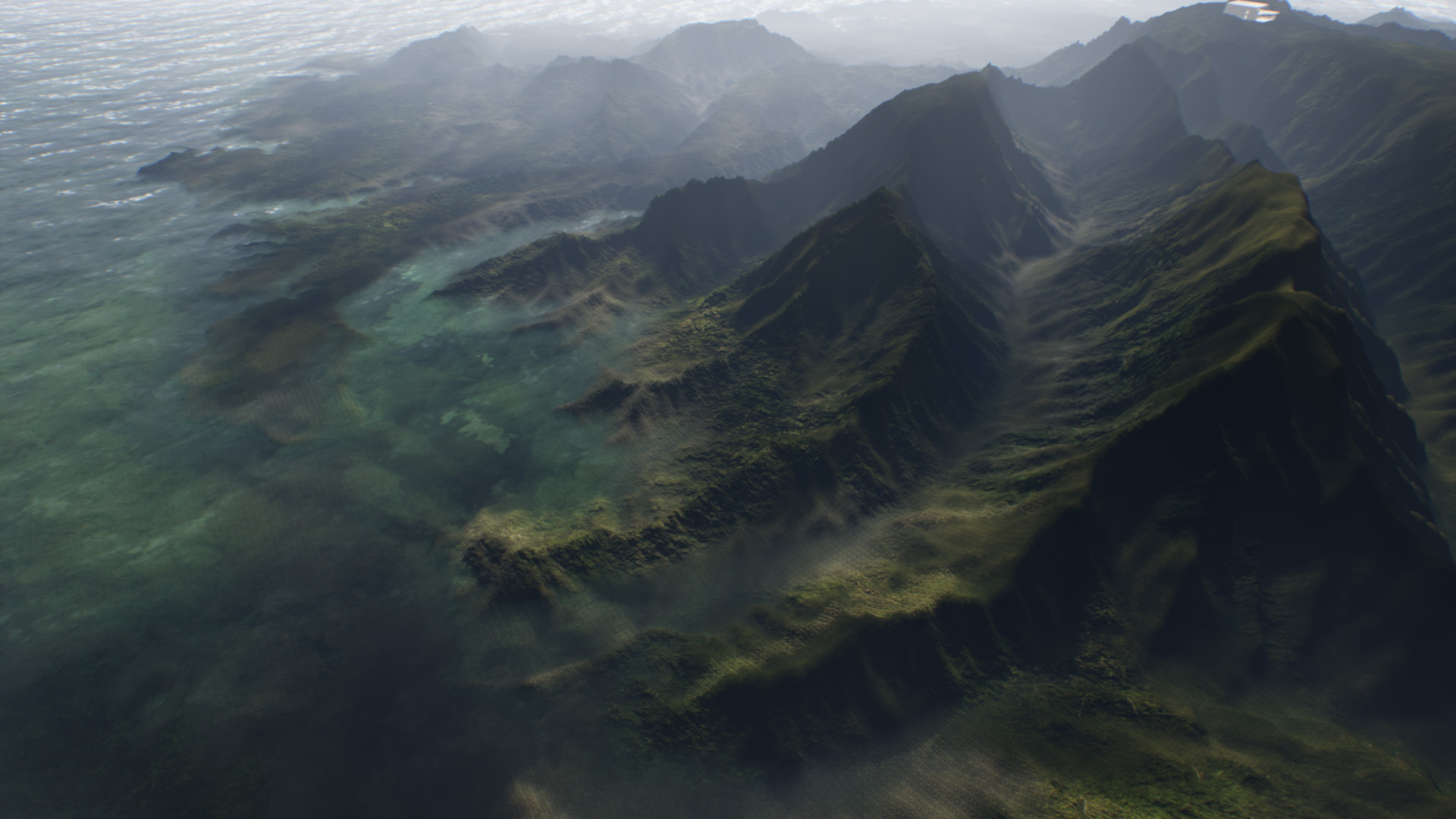

JKS: Liminal Lands [image or image/clip above here] is a new VR work that I opened this past summer at LUMA Arles in France. It’s based on field work that I did in the Camargue wetland, where the LUMA Arles museum is located. Presenting technology and making work about technology has never interested me at all. I know these tools so well that I’m also a little bit bored by them, in a way. It comes very natural and easy to me. So ,to me, it’s like using them in a way to present something that feels very fluid or very cohesive. But for example, when you mentioned Bill Viola and Caspar David Friedrich, it’s like I love what they’re doing with their color scheme. And they’re artists who have like a strong kind of hierarchy, in what they’re doing or what they’re trying to say, very religious imbued or a kind of grandeur kind in their work.

For me, I am drawn to the feeling of being able to create something cohesive that way, that you really feel it kind of like lifted or drawn to. But I like to create it from fractured elements, because I grew up with all this technology, so I feel very fractured in my way of living. I want to create something that feels cohesive, but I’m putting together sounds of something extinct, something that lives. Sounds from an animal, sounds from an insect. These are many different elements and scales that are kind of fractured in reality. But through the virtual, you can meld them together to make it feel as a single unit. I can kind of use the virtual also, not just something that fractures and confuses, but that can actually meld different things together that we normally don’t think relate to one another.

With Liminal Lands, I spent one year at the LUMA foundation and residency. I was looking at the different seasons, taking digital photographs of the light, how it’s changing and how the light changes humidity. When humidity changes in this wetland in the Camargue, the soil can either become liquid and full of little insects and bacteria, or it can completely crystallize and it turns into these rough surfaces. It’s all defined by the sun. Because it can evaporate and everything just goes out of the ground and things just becomes salt, or it is more humid, then it becomes fresh water.

You have a landscape that is changing all the time, from fresh water to salt water. That means, when you look at the landscape, it just looks like a desert, kind of like a gray desert when you look at it at first. But then you look at the detail, and the water one day is blue, then it’s pink, then it’s green. One day you see a branch; the next time, it’s this giant crystal sticking out the ground. You see a bird flying around. When you come back a few months later, the bird has turned into a crystal. I 3D scan this entire bird that’s actually turned into a full crystal, and I present it on this five-meter video wall at LUMA. It’s actually a bird that turned into a full crystal, just frozen in time. Then with these virtual tools, I can connect all of these different elements into something that, as you experience it in VR, feels like a single unified movement. Even though it’s made over an entire year, it feels like an eighteen-minute experience where you move through all of these different environmental conditions, which are completely seamless in their transformation. There’s never a cut, there’s never a change.

There’s no explicit interaction for the audience, where they have to touch or do something. I completely remove this rational approach to technology, where you interact as a direct response. Instead, all of the responses here are more intuitive. You guide people moving through the landscape. As you move through the work, the technology knows the speed at which you’re moving. It knows where you’re moving and it is using this information to change what you’re hearing. If your head is up in the air, you start to hear the sounds of birds and flamingos. Then when you move them into a water pool, the sound slows down and it sounds like ancient dinosaurs, because flamingos are kind of the primordial creature in the wetlands, actually the biggest animal there. When you move down towards the ground, you start hearing insects.

If you move your head into a rock, you hear the rock, and then you can move out of it. All of this movement by the four people is changing the sound, and the sound is changing the visual environment. There’s a kind of a trio going on at all times. You move, things change in the sound, the sound changes how things move, you start moving because things are changing. You’re in this rhythm with the work for the eighteen minutes. The seworks are becoming more like there’s a narrative behind them. But I’m also removing that, so it’s becoming more like this raw sensation of just moving through a landscape.

BL: You’ve carried that forward, quite a bit. These are works you made during COVID, when I was unable to travel and we were all locked down. You were locked in your studio, working and traveling locally. You were in the Camargue, then you were back in Berlin. Currently you live in Berlin, and over the last year you’ve dug really deep into what remains of the very ancient wetlands that used to be all throughout the landscape. Light Art Space in Berlin commissioned your new work, Berl-Berl (2021), which is quite large. Berl-Berl. The title references two words: one is Berl, believed to be a word in the ancient west Slavic and Wendish or Serbian languages, which translates to swamp and served as an early name for Berlin.

The second word in the title is drawn from Berghain, the name of a popular, pulsating techno nightclub that is famous for its very dark, cavernous dance floor situated in the turbine hall of a defunct German heating and power station. That’s where Light Art Space is and where Berl-Berl was shown. When someone entered Berl-Berl, they experienced a virtual version of the primordial swamp. I’m curious, was there something special in your inspiration to conjure the configurations of the living and the bygone amphibians and insects from the wetlands?

JKS: There are multiple narratives around these projects, where one is the technology. But I think with Berl-Berl and my work in general, it’s really not the technology. It’s the feeling for people and kind of reviving a sense of fascination for landscapes that we know and that I think about. For the past two years, I’ve been working on wetlands and Berlin. As you mentioned, Berl is this old Slavic word that was used in the region to describe the area. Also, it means swamp. Modern German adds an “in” on all the old Slavic words. So “Berl” becomes Berlin. It’s one of these Slavic words that is modernized in German.

Also, I was really struck by how, since the 1700, most European cities have removed their wetlands, because they were an antithesis to the modern mind and the way it thinks about space. A landscape in the 1700 had to be good for agriculture, for industry, or for beauty. The wetland and the swamp were none of that for the modern cities. Ironically, the type of landscape that is essential for human survival is a wetland, because it’s what creates fresh water. Any large civilization in the world was actually founded by a wetland, unless it is a Nomadic people, who travel to where the season brings them to different wetlands. We’ve kind of forgotten this and that’s why there’s a water shortage floods, and these kinds of things, because all the wetlands have vanished. I began Berl-Berl in Berlin with the natural history, as well.

I was looking into the forgotten wetlands, and I worked with the natural history museum. But along the way, I began stumbling upon words, songs and mythologies from the wetlands in the past. I started to think, what does it mean to try to revive, not just the fascination with the science or like the specificity of an actual landscape, but also on ways of perceiving a feeling or moving through a place from the past, which is far more abstract. I started to work with this language researcher Sabine Asmus an artist and PhD student in London Dane Sutherland, on creating a whole library of words and stories and songs from the past. We ended up with a hundred pages of material. Then from that, I got it down to about twenty pages. From that I isolated a few different mythologies and songs that became key for the whole project.

So, you enter Berghain and you enter this immersive installation, but you’re also entering a song. It’s this environment that’s singing these vocals that then moves around the building. It’s also an instrument. It’s this virtual swamp-scape that is changing all the time. It’s kind of alive. As things are changing virtually, as when an insect flies by a specific screen or somewhere virtually, it’s also moving through the architecture and sound. It’s really hyper-spacialized sound in this space with what’s actually in the virtual and they talk to each other one on one. You’re entering this strange place that used to be a nightclub. Now it’s an immersive, virtual, colorful environment, but it’s also an instrument and a song, and there’s like a strange navigation going on. It’s a project that became about this navigation through a landscape, very much inspired by old Serbian and Slavic folklores.

There are these songs that were sung at night when people would go out and sing to the nymphs of the swamp; some songs are very ambiguous stories. Again, a lot of the wetland cultures I refer to don’t have the same dialectic way of thinking about a place, which Christianity has, with heaven and hell, our world and the other world. For the ancients, you can go back and forth. One song is about a man that falls in love with a nymph. First, she brings him into the waters. He kind of drowns, but then gets back out. They fall in love. He leaves the village, but the village doesn’t like him for leaving. He moves into a tree in the swamp with the nymph, but then comes back out because the swamp king is kind of mad. It’s very ambiguous about what’s going on.

Many of these songs were used for navigating landscapes. The key thing that I really found interesting was that the wetland cultures of Europe are referred to as singing cultures. Their primary means of sharing information, story, ethos, culture was through singing. Whereas we’re a tech society, back then it was a singing society, and songs always change. There’s no definite version of any one song or story. When I talked to singers in the region, they also noted this. I asked them, how do they feel about my making an artwork inspired by their culture? They said, “Oh, we’ve always been doing this. The songs can always transform.” They adapt to the changing world. I don’t know where I’m going now. It was new for me to work with song more explicitly and a cultural history imbued into the landscape. It has been very new and exciting to me.

BL: That’s great. I know that you had a big team that you worked with, including a specialist from the Natural History Museum in Berlin. Also, you worked again with Matt McCorkle, who’s been your sound designer.

JKS: I worked with Matt McCorkle many times. He normally makes the sound installations for the Museum of Natural History in New York. I have this thing of working with experts from other fields, people who might want to explore their practice in another way. Matt and I do field work together. We sail through the wetlands in canoes and record. Then I send him different stories that I found in my research. Then he creates sounds for them. Then Arca sings different vocals and actual words, like Berl, Birl, Bre, Bro, four different words for ways of saying Berlin in the past, and singing them. Each time she sings a vocal in the installation, the installation shifts and changes. It like shuffles different things that can happen in this virtual swamp. It takes a big team to create something like this.

There’s also super talented network programmer, Wouter, a young guy from Belgium who works now part-time in my studio. There’s an absolutely fantastic sound artist, Lugh O’Neil, from Ireland, who’s based in Berlin, an amazing guy who’s able to fine tune how sound moves around the architecture. But then it’s like, everyone is doing things physically isolated from each other, but they connect to make this strange artwork that no one really knows what it is. Matt records the sound of an animal, and I give that animal sound to Lou. Lou puts it across the building in the architecture, but the sound is moving around together with the multi-player system that Wouter made, which connects to the way I move the virtual camera. When I move the virtual camera, when I change what it’s looking at, the sound will change and shift. Everything is connected, but no one is a “mastermind.” I made a design for the work, with the intention that I can’t fully explain the full pipeline or sequencing of it all. No one really can. And it’s very intentional, because that’s very swampy. If you try and control it too much, then you’re going back again to this modern, rational way of trying to define landscape. And that’s not what the swamp is; it’s supposed to be more undefinable.

BL: Berl-Berl is an incredible artwork and exhibition that just closed in Berlin. Will it go anywhere else? Can it go anywhere else?

JKS: Yes. Berl-Berl is made to be an instrument that can take over an entire building. It’s completely modular and can be set up anywhere. It’s also made for performers. I worked with another artist for the closing, Pan Daijing, who was making an opera inside the work and the work was kind of responding to what she was doing. Berl-Berl is a work that’s made to grow, to change, and to adapt. It’s a virtual world, but it’s also a stage for performance and poetry, at the same time. I’m working on figuring out where it will show next, but I can’t say where they are yet.

BL: As an artist, you’re in demand and you’re always on the go. Sometimes I’m breathless just trying to keep up with you. I know even though you live Berlin, you’re speaking today from Copenhagen. Now that travel is easier, should I book a flight for a new project you’re developing in Denmark?

JKS: Berl-Berl will be shown at ARoS in Denmark next summer.

BL: Okay, I’ll book a flight.

JKS: Also, we are touring my work from LUMA, Liminal Lands, at film festivals. It’s start in London, go to Geneva, and hopefully will be presented in the States at Sundance. Also, I will publish Liminal Lands online. Increasingly, I’m going to start bringing works to people. I want my work to occupy these large immersive spaces, but also film festivals, which are more dynamic formats with one-time setups. For me now, it’s about embracing multiplicity and working with a lot of different artists. I’m building a platform right now that’s growing. I’m no longer fully in control.

BL: That’s very exciting. Now this is my last question, and it’s something I’m asking each artist I’m speaking with in the podcast series. And you’re a good person to ask this. Given the ups and downs of the last eighteen months and the struggles some of us have faced in trying to adapt, how has technology affected you and your practice in the last year and a half?

JKS: A lot. I love collaboration, so it’s been hard spending so much time alone. But I have also built virtual tools that allow me to collaborate quite effectively, even though we’re in different places. Especially for the creation of Berl-Berl, technology has influenced how I’m able to work with different artists through virtual reality and enter the artwork together. We can discuss the project and give feedback to each other, even though we are in different locations. I build the landscape, then I invite people to become part of that landscape. They can do that physically—that means space and performance at work in our studio—or remotely. Everything kind of connects now.

BL: That’s wonderful. I can’t wait to see more of your work and hope to see you soon in the virtual and in the physical.

JKS: Yes, I hope to see you soon, Barbara.

BL: Thank you so much for joining.

JKS: It’s been nice.

BL: Thank you.

—

Support for Barbara London Calling 2.0 is generously provided by the Kramlich Art Foundation.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

The series is produced by Ryan Leahey, with production assistant Vuk Vuković. Web design by Vivian Selbo. Special thanks to Lee Ranaldo for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded August 2021; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Images & Video