[December 1, 2021 | Season 2, Ep. 1 | Barbara London Calling]

Barbara London: Welcome to Barbara London Calling 2.0. I’m your host, Barbara London. In 1974, I founded the Video Media Program at the Museum of Modern Art, where I was a curator for 40 years. Last year, I published Video Art: The First 50 Years, the first in-depth history of video art.

Today, with technology as ubiquitous and as fluid as water, I’m interested in how artists adopt technology to their own artistic language and vision. In Season 2 of Barbara London Calling, I’m speaking with 12 artists from all over the world, each challenging the entrenched definitions of what art is and what it can be. These 12 artists and I will explore the role of technology in contemporary art today and where it might take us tomorrow.

Today, I’m speaking with Auriea Harvey, a boundary-breaking artist born 1971 in Indianapolis, Indiana. In 1989, Auriea moved to New York to study at the Parsons School of Design, where she received her BFA in sculpture. Before long, she began creating Internet art, video games, work in extended reality, and recently she moved on to NFTs. Auriea is now based in Rome, where she is calling from today. Auriea, welcome to Barbara London Calling 2.0.

Auriea Harvey: Hello, Barbara. Great to be here.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: Auriea, you’re known as a true pioneer in net art and new technologies. I’m curious, how did you make that leap from sculpture to net art?

AH: The move from sculpture to net art was pretty easy because I had been using computers a lot in my artwork, even though in the early ’90s it was quite early. It was a time where there was nothing to really base your use of computers on artistically. I was thinking about how I might use computers and was experimenting with very early versions of software, like Photoshop and some sort of programmatic 3D programs that were around on IBM PCs. I worked in desktop publishing, using computers to help art directors who were then still doing paste up. I was translating their designs into computer programs—in other words, into layout programs.

I was already thinking along the lines of, How can I use computers to create my artwork?

Basically, I was a sculptor living in New York City, but I had no space to sculpt. The computer had already become this thing that I thought of as a way of saving space, you might say. Then when I saw the internet, realized I could have my entire artistic practice on the web, creating artwork that people all over the world could see very easily if they had a computer, as I did. Then it felt very natural actually to start creating net art.

BL: Around 1999, you became a member of what to me is—or was, back then—an intrepid net art collective: hell.com.

AH: Actually, it was 1997 or 1998 when I joined. I can’t remember which, but it was quite early. I was a member of the collective for a while before I actually met my husband, Michaël Samyn, and moved to Europe, which is ultimately what that culminated in. After that, we were working in hell.com together.

BL: What was it like? You were in New York, your husband-to-be, Michaël, was in Belgium, while other artists were from all over the world. I believe the generative artist LIA was from Austria. Others were in the U.S. and Europe.

AH: LIA was in Austria. We later found out that the duo JODI was in Amsterdam. There was Antiorp (aka Netoschka Nezvanova), who was from wherever Antiorp was from. Joshua Davis, from the United States, other people from a lot of different places—there were quite a few people who are still in digital art circles. Much of that history has unfortunately been forgotten now. It was a fun and really interesting early example of a collective art experiment online, based around a server.

BL: Rather than gathering around a fireplace, you gathered around the server.

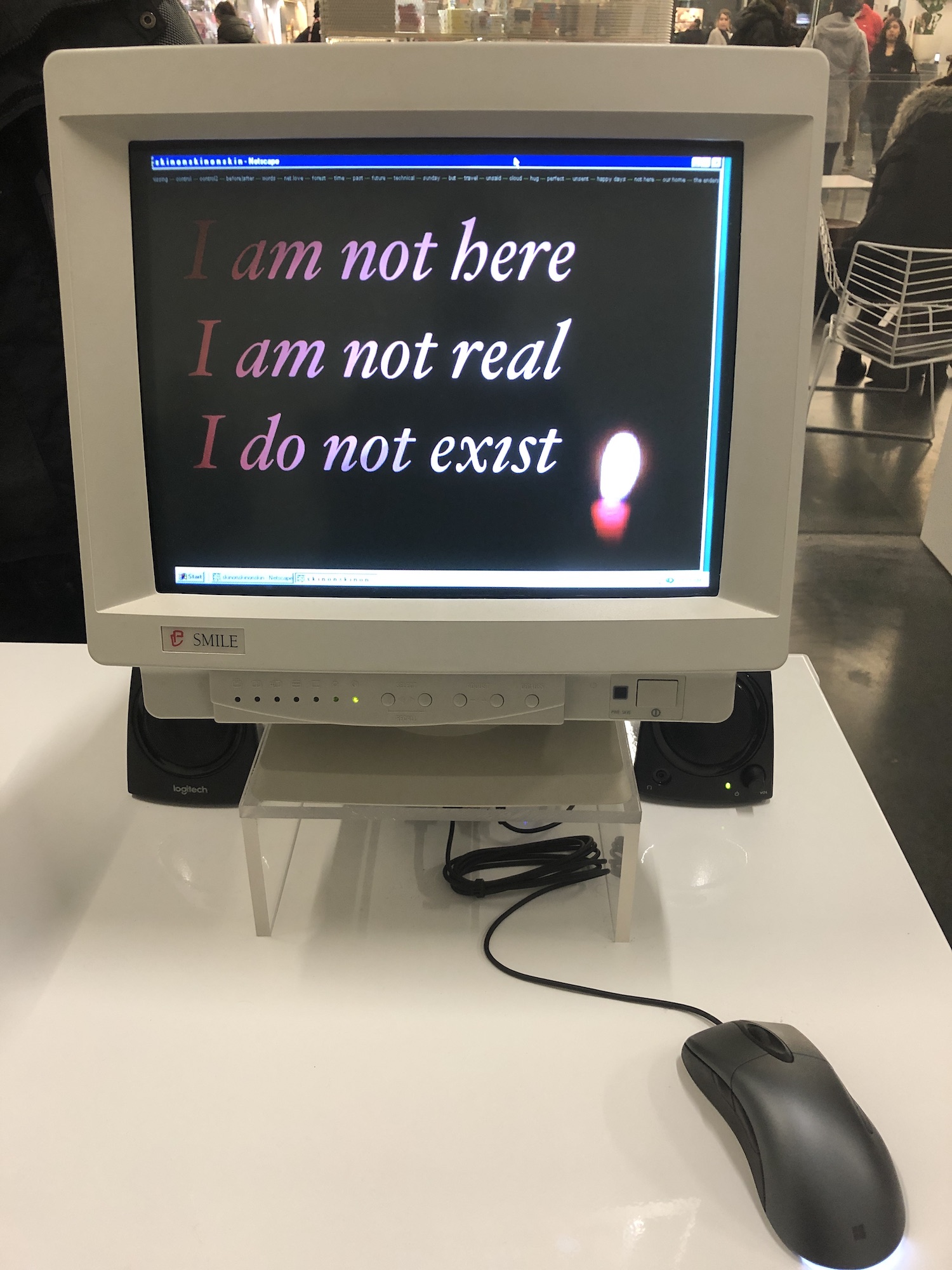

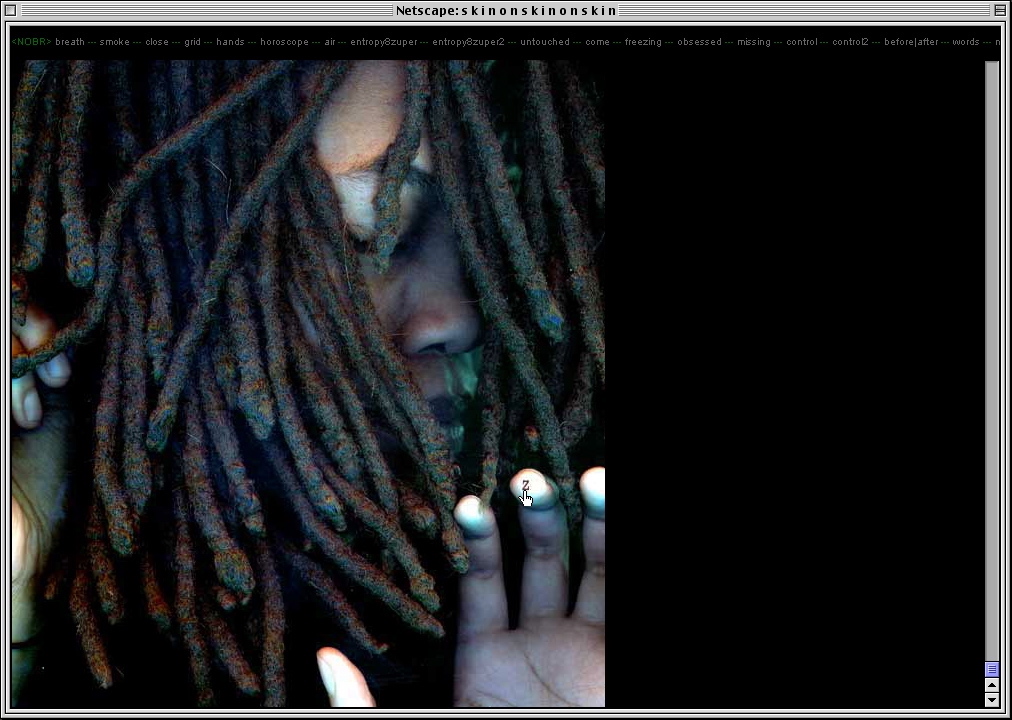

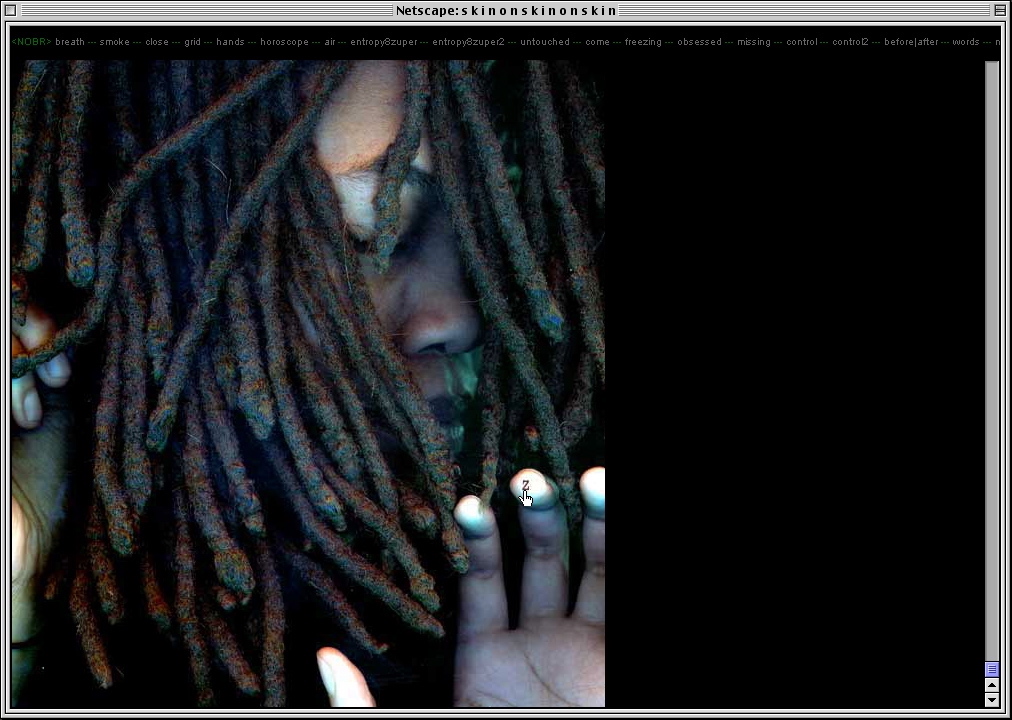

AH: Exactly. It was at a time when you shared a server with people, and you trusted each other with seeing directories and files. When Michaël and I made our first project together, skinonskinonskin, it was on the hell.com server and we didn’t hide anything. Eventually the project was found by other people who were like, “What’s this? You guys have been working on something!? Are you going to release it?” Our answer was, “No, no, not yet.” So, we kept it sort of semi-private for quite a while, before we actually turned it into pay-per-view, which was another early experiment. Would people pay to see art content, so to speak. But we were doing that mainly to protect it. Again, we felt like we wanted only people who really wanted to see it to be able to see this piece of ours.

BL: Was it pay-per-view for a couple dollars?

AH: I think we actually charged $10 to get in. When people paid, it was not like we became rich or anything. Afterwards, we always gathered their thoughts. People who came to see the site were trying to figure out whether they wanted it or not, so they could read people’s reactions, which were often quite emotional. It was really good.

BL: I imagine you had mostly positive reactions.

AH: Mostly. But that was the other thing: We didn’t want people to take their experience for granted. At the time, people were really into looking at net art sites very carefully and thoughtfully.

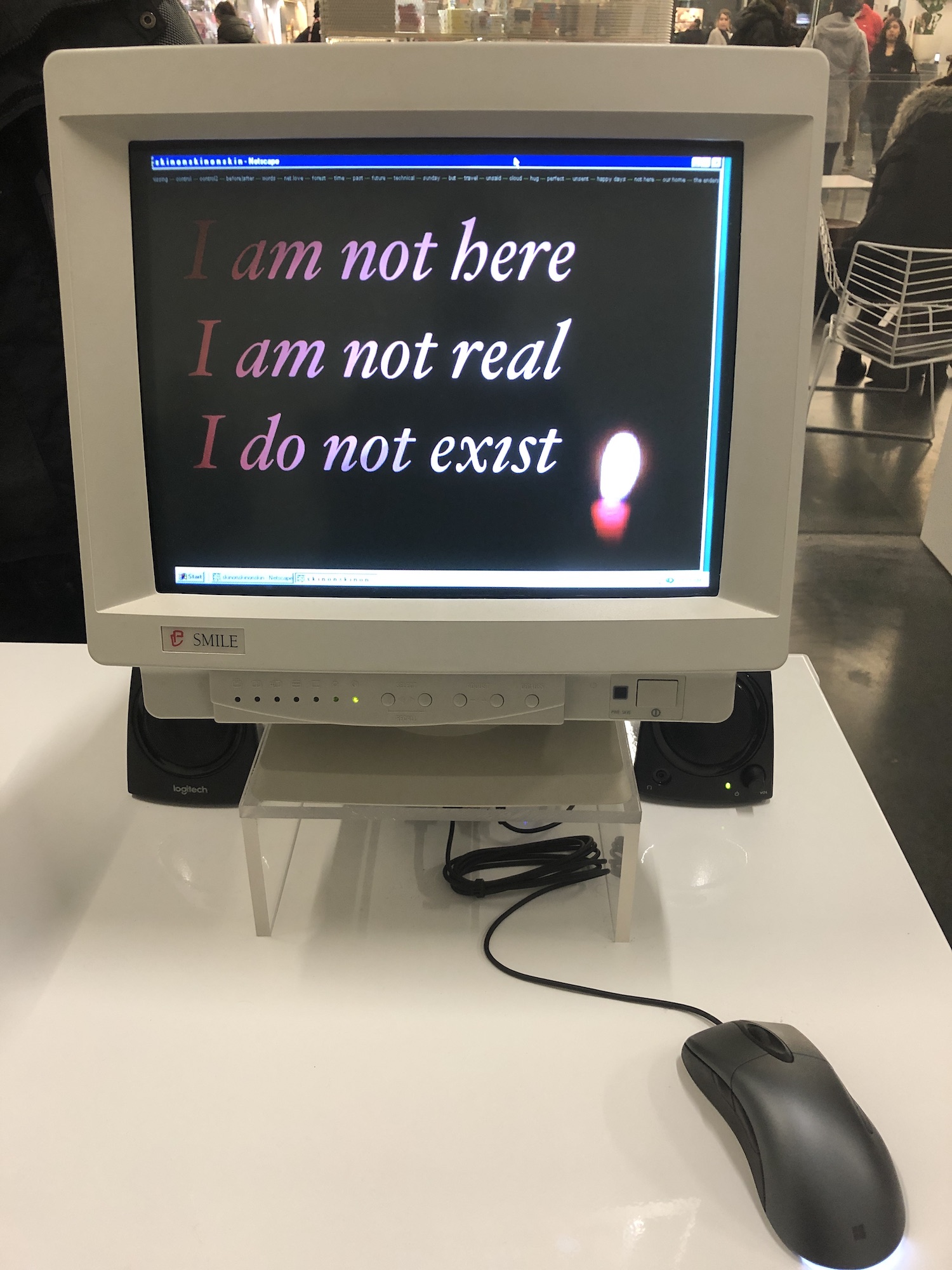

BL: This brings me to perhaps the first video work you ever made: Webcam Movies.

Auriea Harvey, Webcam Movies. 1999. Webcam Movies, 1999. Video (color, sound), CRT monitor, media player.

AH: Well, yes, the webcams… Actually, it was not a video work, as such. It was live camera, and I happened to have saved a few of the clips of myself from that time. It’s kind of a miracle that anything survives of it, because it was a real-time thing. It was something that was just the camera on my desk. But I was very much aware that the camera was there. I was aware that people were connecting to my website to look at me sitting at my desk. It was a strange thing for someone to have at that point; when a person got to the website, it was me full screen in the browser at a time when there wasn’t a lot of bandwidth for these sorts of things. But I had worked out how to do it, in that I had a high-speed internet connection in 1998, 1997. This black-and-white camera was on me for a couple years, before I left New York City. I had a T1 line, and I’d found some software. It was actually a primitive form of streaming.

Actually, the software pushed an image every so many seconds. It looked like a real-time video, but the software was simply sending still images, one after the other. The black-and-white images were actually quite small, but I blew them up. They had this look of sophistication, like an art film almost. I could see everyone who was connected to the camera—who was connected to the site, rather—because I was hosting the site out of my apartment. It was this way of me communicating, I guess, with whoever would come to the website. They would email me and we would have discussions. It was rather cool, at a time when this was very difficult to do.

BL: It was difficult, but quite exciting, I would think.

AH: Yes, it was very exciting. I met a lot of people through this. Now it might be a strange thing to do, or not so strange. I don’t know if it would be stranger now or not, or more common. But it was definitely a special thing to do in 1998, 1999.

BL: It was in 1999 that you moved to Belgium to be with Michaël Samyn? I gather it was that year you founded what you call Entropy8Zuper!

AH: Entropy8 was actually my website starting from 1995. And that’s the moniker that I did work under while I was living in New York City. Michaël had Zuper.com, which was his alias. So, when we met, we just decided to combine our two sites in a very plain way. “Two coms make an org,” so that’s how we had a merger. We were joking about it being a merger, Entropy8Zuper.org. in 1999, after I moved to Belgium.

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, entropy8Zuper.org. Website.

BL: Was this merger for both of your art practices?

AH: Absolutely. When we met we wanted to just do design together, because we were both doing exactly the same thing in two different places. We were both doing net art, but we also both did, for lack of a better word, commercial web design. But that was a very different thing back then. It was much more custom. It wasn’t like we had to be a business. It was like people asking us, “Will you make our website?” So we did that.

I had my clients in New York City, some pretty interesting ones. I was working with Virgin Records on websites for rock stars like Janet Jackson and Lenny Kravitz. Michaël was working with organizations in Amsterdam, for different festivals and things like that. To make a long story short, we were just trying to have a business together. Then we started doing lots of other work and fell in love, and the rest is history.

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, The Godlove Museum. 2000-2007. Website, custom software (color, sound). 20 min 11 sec, loop.

BL: I’m fascinated by the connection to music that I sense in your work. I have always been interested in the important role sound plays in the moving image, the connection between video and sound. I read or you told me that your mother was a jazz singer.

AH: Yes, yes. When she was younger, my mother was a singer and she had a band and was quite well known in certain circles. But she stopped singing when she had children, then worked most of her life as a paralegal. But she never really stopped. She would still go places, and people would remember her and ask her to sit in if there was a jazz in the park or something like that. She took it up again later in life very seriously.

That is to say that I grew up listening to all of the great jazz standards and understanding this notion of what it means to do a jazz interpretation and improvisation. I think, on a certain level, I took that to heart. Music is a big part of my work, but not in the sense that I’m a composer or whatever, because I don’t make music. And I am shy about using music in my work. I don’t really want to trivialize what music is or can be. But at the same time, I think this theme, this notion of jazz standards, of songs that are meaningful and that are sung and re-sung and have meaning in culture and become new again, when interpreted and reinterpreted—this is something that comes in my work. Not in an obvious way, perhaps, but it’s definitely in there. And I’m very much a singer, myself, without really being good at it. I’ve got this bug for singing, even though it’s not my art form. In other words, I sound awful.

BL: Later we’ll get to this, the way you work with myth and history.

AH: The singing does very much relate to this. I was just thinking that the videos you might be thinking of are the ones where I’m looking through my sketchbooks and I have some musical accompaniment. It’s just songs and me singing along, while flipping through the pages of the sketchbooks. I think in that sense, in that series of videos, which were very simple things, they’re made as a way for me to look again at my early sketchbooks. All of my sketchbooks are very precious to me, as any artist who keeps them. I’ve kept sketchbooks since I was a child, 12 or 13 years old. I still have all of them. It’s a whole lifetime of drawing and sketching.

These videos were made to re-look again into these books and to think about who I was when I made them. At the same time, the videos have soundtracks of songs that were meaningful to me at the moment that I made the videos. I’m singing along, and I’m moving the pages along to the music. It was just an activity. I don’t know that I thought about it too much when I did it, but now when I look at them the music takes on another dimension, and in a sense adds another layer of time. There’s the time in which the book was made, the time in which I made the video, and that time of me now recently looking at those videos. It’s kind of an interesting layering.

BL: The sketchbooks are quite beautiful and the process of you reviewing them is very special. I loved the way Sketchbook Movies was shown in your recent exhibition at bitforms gallery, where it was simply presented on a flat screen in the manner of a rare book. The video is so visceral, because the pages with photos or drawings or texts pasted in become stuck at times.

AH: On some pages, there’s a pop-up. A whole pop-up heart comes up, and I’m pulling it apart. The sketchbooks have a certain sense of being a container. When I want to keep something, I’ll put it between the pages, so the books have that quality.

Auriea Harvey “Sketchbook Movies,” 1990–2012 – Excerpt.

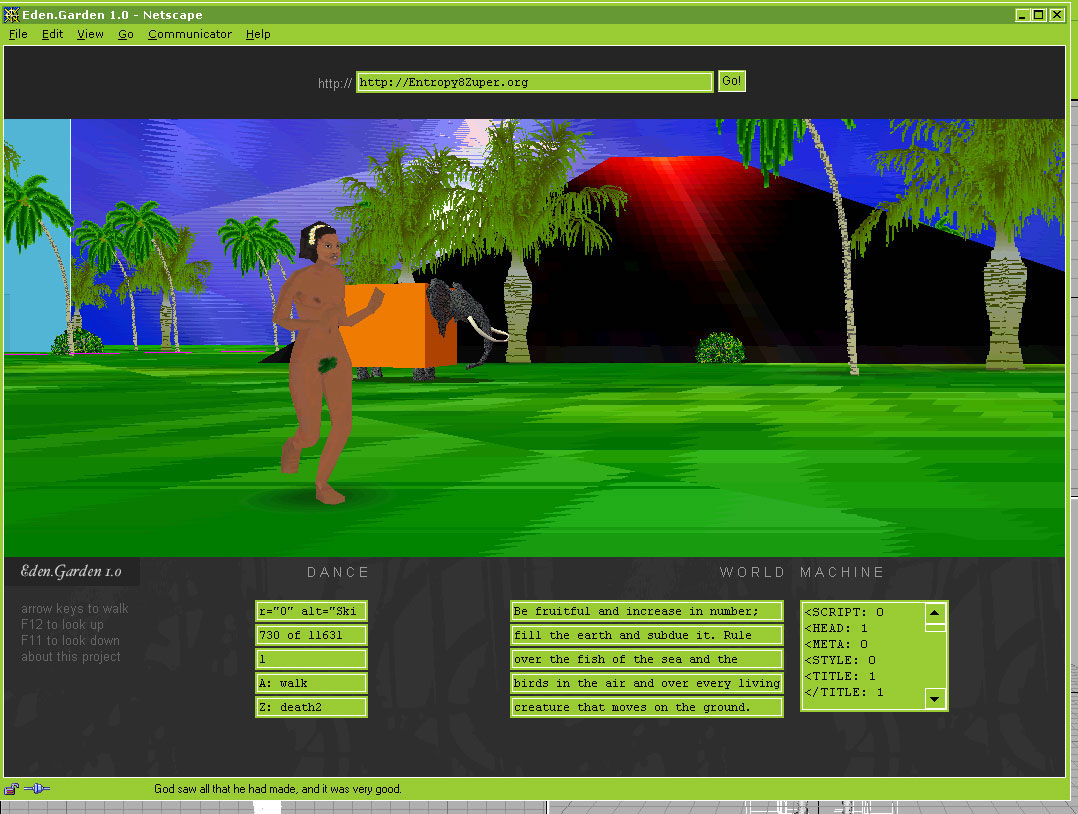

BL: Let’s turn to 2001, when the prescient curator Benjamin Weil at SFMOMA commissioned you and Michaël to make a new work for the exhibition “010101: Art in Technological Times.” As artists, you and Michaël perfectly fit the bill for Benjamin. What you made was considered interactive 3D, a technology you had known very little about until then. Tell me a bit about the inception of that piece and your investigation in the medium of interactive 3D.

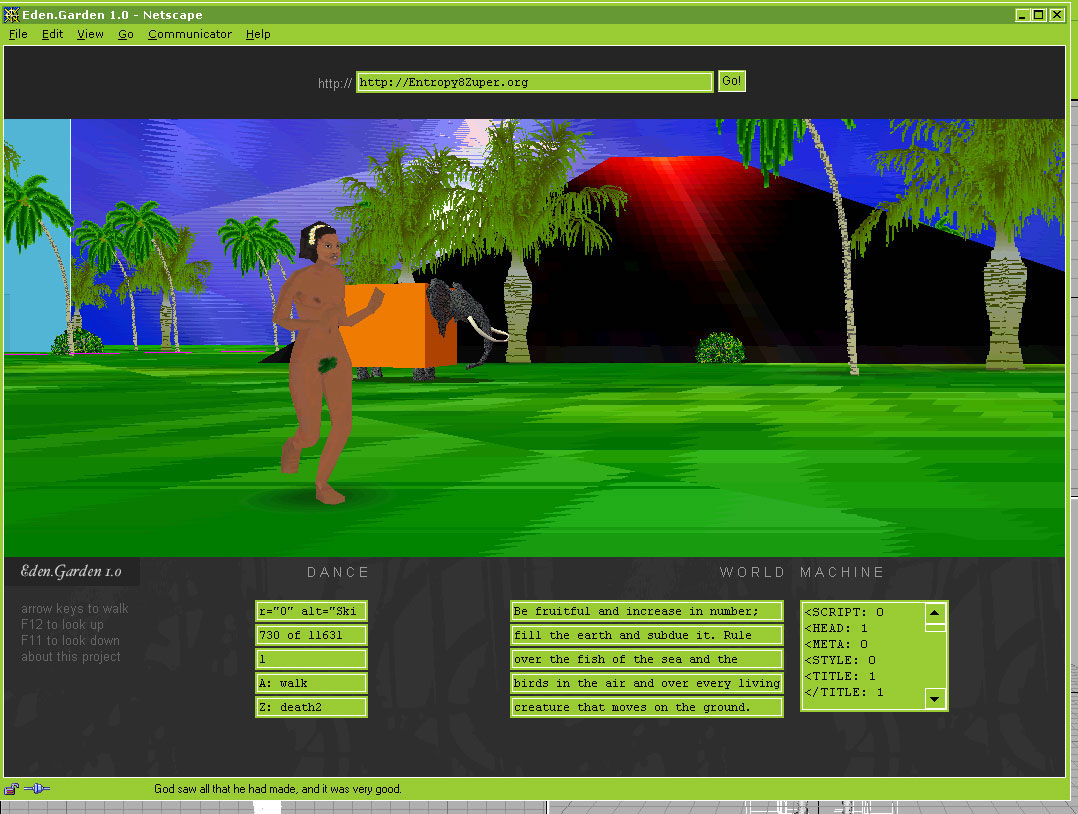

AH: Michaël and I had been doing a couple of small experiments in 3D on the web. As you may remember, back then you had to have a plug-in in order to view just about anything extra that wasn’t text or image. You had to have a plug-in for your browser. We had experimented with Blender 3D, which had a plug-in at the time, and we created a couple of pieces with that. But then when we were invited to do a project for “010101,” we decided to go all out. We found a company that had created a real-time 3D plug-in that really worked. We created an alternative browser that was like a browser within a web browser.

What ours did was, if you typed in a URL, it went out and it parsed the HTML of that file and then translated all of the HTML tags that it found into a 3D object that we had predestined. So, if it found font tags, for example, it would create rabbits. If it found a table tag, it would start to create a forest. Different colors of the sky had to do with background tags, things like this. Ultimately, what we were trying to create was a garden of eden. So the project was called Eden.Garden. It revealed this kind of paradise that was behind every single webpage. That’s how we put it, because that’s what we felt the web was at that time and a little bit before.

It was a paradise we didn’t want to lose. We wanted people to see that every single page could turn into something beautiful that you could explore. Ultimately, after it generated this garden, your own Eden.Garden, you were able to walk around inside of it, where you would find Michaël and me there as Adam and Eve dancing around in the garden. There was a twist, where if you clicked around you could start to follow and make one of us your avatar. Then you would see that the camera you had been guiding around this whole time was actually the snake in the garden. It was quite a funny project.

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, The Endless Forest. 2005/2021-ongoing. Online game.

BL: So, Eden.Garden was full of history and myth.

AH: Our transforming of what is pure data, or what is just a regular webpage, into something that was more fantastical and explorable, is a recurring theme.

BL: I gather, it was just a year after that you went on to become a game design researcher at the Jan Van Eyck Academie in Maastricht.

AH: It was research in design. The way the Jan Van Eyck Academie works is that you get a stipend and you become a researcher there. In effect, you design what it is you’re trying to research. We decided we were researching video games, because we wanted to make video games after that experience with Eden.Garden. We thought, Why don’t we just stop thinking that we’re only going to make net art. Let’s make actual video games, because we had been so admiring of the fact that this interactive art medium seemed very underexplored. I wanted to continue with 3D very much, and we both felt like this was a very futuristic endeavor.

But at that time there was very little information available about how video games were made. It’s not like today, when there are lots of sites where you can go get a tutorial. It was much more involved back then. So, we took that two-year opportunity at the Jan Van Eyck Academie to attend game developer’s conferences, to ask other game developers who were making the games that we were playing how they did it. During the course of this, the independent game scene kind of took off, and we became a part of that.

BL: How did you become a part of the independent game scene? I know you made a very successful and very beautiful game called The Endless Forest in which you have deer that have human faces.

AH: The Endless Forest was our first release in 2005. Of course, we made other games during that research period. We made a game called Eight, which was never released for all kinds of reasons that are probably beyond the scope of this conversation. But suffice it to say, we made The Endless Forest with the help of the Mudam Luxembourg, which at the time didn’t have a building yet. They are a contemporary art museum, but without a building then, all of their initiatives were online. They asked us to create a work of net art for their online gallery. Instead, we said, “Can we take this commission and make a video game?” And that became The Endless Forest.

The first versions of that multiplayer networked game, the networked prototype was served from Mudam’s server. They distributed it for us. They had this notion of patronage at that time; they believed it was worthwhile to support artists in that kind of way. We went on to release that game. Actually you can still play The Endless Forest; it’s still available. In fact, we’re remaking it now because so many people were still playing this multiplayer game. We wanted a world that would just always exist out there in cyberspace. Even if we couldn’t be there, we would know this world is there. And it does exist. It’s there, populated by all kinds of animals and deer. As you say, it’s not a normal deer. It’s a human-faced deer. And it’s not just a regular forest: It’s a magical forest.

BL: You have a wonderful interest in the magical, in myth, which means The Endless Forest has a history.

AH: I think every single technology that I’ve been attracted to, I’m only attracted as long as it feels like magic. There’s always a sense of magic in a multiplayer world. There’s always this feeling of, oh, that’s another person that I’m meeting, but they’re sort of inside of another body. Right now, they have turned themselves into this other creature. People really do try to embody those creatures that we’ve allowed them to take on as avatars, and that’s kind of a magical thing.

BL: You have pursued and you continue to pursue all things digital. But it seems that in 2013, you made a U-turn back to what we would call traditional art forms. I know that you’ve always drawn, and when you’re at a museum you always go to the drawing department first. As a medium, drawing is important to you. Several years ago, you studied drawing at the Studio Escalier at the Louvre in Paris. Then you studied clay modeling at the Studio della Statua in Florence.

AH: These are workshops that were very formative. Over the years, I’ve taken a few different workshops in traditional art, which have really saved my sanity quite a few times, and have given me a grounded feeling. Throughout my life, I think I’ve always gone back and forth between being purely digital and then having to back up and get my hands back into something more foundational. I don’t really know why that is. This pivot back into sculpture, has actually turned into a pivot back into the digital. I can never work with just one medium. There’s always a combination. Taking these workshops—like I did in Paris at Studio Escalier, where I was every day in the Louvre drawing from life, from the model in their studio—these kinds of things always take me back into what is fundamental.

One can forget that when using technology, things can be mastered. With technology, you’re constantly searching. You’re constantly learning. You’re constantly relearning and forgetting and trying again. You might get really good at a certain digital tool, and then suddenly that company will get bought or it will fold. For example, with our Eden.Garden, we created this whole world based around the fact that we could use this plugin. Well, that plugin company who made that plugin quickly went out of business. That piece cannot be seen anymore. It’s now just a memory, which is wonderful. On one level, the digital can be more like a performance than like a marble statue. But sometimes I need the marble statue. Sometimes I need to get rid of the electricity and just use the charcoal and understand that there can be something that I can see progress in, and the tool doesn’t change. The charcoal itself is just a burnt stick that isn’t going to change on me.

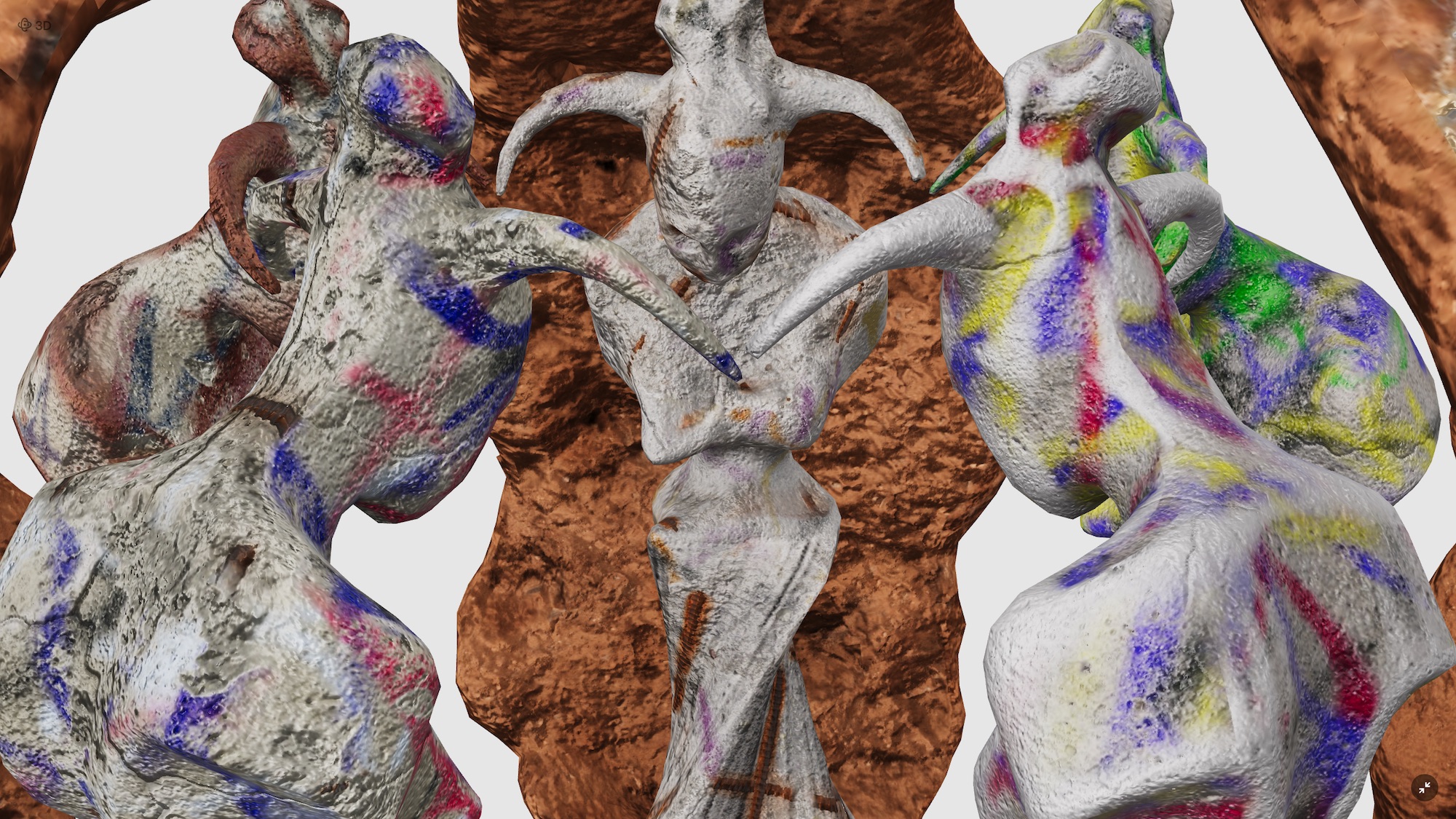

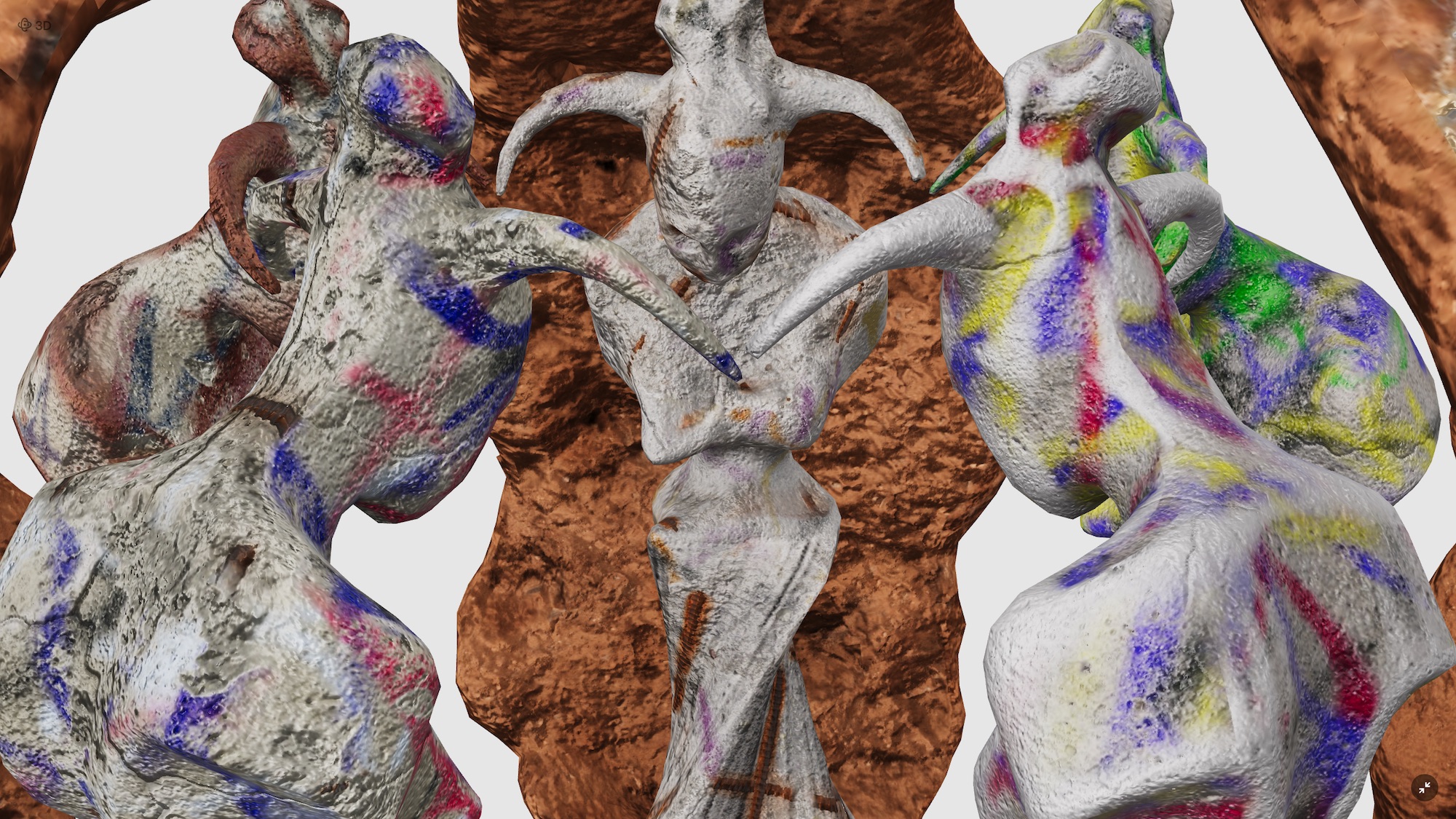

Now I was trying to get back into pure sculpture. Albeit my sculptures are 3D printed, and they’re a combination. It’s like this combination of the technological and me collaborating with a machine to 3D print the sculpture. But at the same time, when the work goes out into the world, I have to take it one step further. I always have to hand finish the work. It ends up being sort of an amalgamation of part machine made from the digital sculpture that’s in my computer, but then partially made from clay. And so, the work ends up as this strange hybrid of synthetic and organic, you might say. That’s what my work is looking like today.

BL: Before we go on to NFTs, which you’re also involved in, I believe you acquired your first 3D printer back in 2016. Was that early?

AH: It wasn’t as early as it might have been, but it’s when the quality of 3D printing became such that I felt it had that magical quality. It wasn’t so much about the machine as it was about the thing that I had created in the computer, in the first place. The digital sculptures that I make are, in and of themselves, these kinds of amalgamations of 3D scans that I’ve taken myself or of myself or of a model. I’ll find an object in the world that I think would make a good addition to the form, or I’ll just sculpt something from scratch. Usually, the subject matter lends itself to all kinds of different shapes and ideas. I’ll try to refine this until I feel like I’ve told the story through the form of the sculpture. These are our output via 3D printing in different materials, and that’s one thing that I enjoy exploring.

That’s one thing that I enjoy exploring is the material narrative of the sculpture. That’s one of the joys of sculpture, this material narrative that you can have with the sculpture. I’ll try to use certain types of materials that aren’t just plastic, but they’re plastic and metal, or there’s wood-based filament materials, or I’ll use resin in various colors that I’ll color myself or hand dye. I try to make people question what the material actually is; there’ll also be clay involved or paint, or something. I’m not about this purity of material, ever. For me, it’s about illusion and storytelling.

BL: I was taken by a very beautiful, tiny sculpture that you made, based on your head. It’s like a young faun.

AH: Yes, it’s called Fauna.

BL: It’s beautiful, just gorgeous in its look and in its texture. A few weeks ago when I went to bitforms gallery to see your popup show, Fauna was there in her full glory, physically and also in an NFT. I’d love to know what fascinates you about NFTs. At the moment, are they a kind of a hot trend, or is the NFT a new form?

AH: That’s a good question. I can’t tell you exactly what NFTs are, or what they will be. But for me it’s an interesting format for digital art, something that people can understand right now. When I had my solo show, “Year Zero” at bitforms gallery, it was the same time that NFTs started to become something that was part of the normal parlance. I couldn’t ignore it. I also had digital work. It’s like I was having a show of my physical sculpture, but it felt like, “Wow, okay. I can show my digital work on the same level as this.” Which was a first. In all my years of making digital artwork, the digital never lived on the same level as the physical, to the point where you almost had to convince people that it was art at all. That was always frustrating, very frustrating for digital artists and new media artists.

I looked to NFTs as a way of showing people the work that I had been making all along. I mean, as digital artists we’ve been here, we’ve been making this stuff. It’s like, “Okay, so now I can show you this in this other way, and talk to you about it in another way, and be taken seriously about the fact that I’m showing you a digital work of art.” The thing that I had come up with towards sculpture was that, each of my physical sculptures has a digital double. However, the digital is actually the primal object. It’s the real sculpture in a lot of ways, because it is the digital form from which the physical is derived actually. During that show I was presenting these as AR models, as digital AR sculptures, augmented reality sculptures, as a way of making people feel that they were as real as they were for me.

I see this digital work as being very physical in a way, very real. Here’s a way you can see it that way, as well. Then all of a sudden, it became something, a way for me to show people this sculpture anywhere they happen to be. In in some ways, it felt like a very internet 1.0 gesture. It’s like, look, you can be anywhere and see my sculptures. This is interesting. Then that sort of melded perfectly with what NFTs were or have become. And so, I’ve continued this practice.

To me, the digital sculptures don’t have to be NFTs. But I think this format allows for a type of discussion to go on that didn’t happen before. That’s actually what I’m interested in, that discussion between the physical and the digital, between the real materials that I’m using and the digital materials, which become a whole other story. Another interpretation of this sculpture, in that those digital materials can be anything, fantastical or illusionistic. And that’s really fun, I don’t know, fun. It’s a different way of telling the story.

It’s very exciting to be able to tell the story of the creatures that I’m creating, the characters that I’m creating, and the worlds that I’m making in different ways. These different interpretations of the same sculpture are, I don’t know, I find this extremely interesting, as it starts to blur this line between the virtual and the real. This is what I’m in it for.

BL: That’s a beautiful explanation. This takes us to my very last question. Over the last year and a half, we’ve all been home, where we’ve been gathering news online and communicating. I’m curious, and would love to know how you feel. In the last year, how has technology affected your how you work?

AH: That’s a very good question. The funny thing is that my art career as a sculptor, which I only got back into in this last year, actually has all happened under lockdown. I achieved my first solo show remotely with bitforms. I stayed in Italy the entire time. We installed the work; I did live virtual tours of the show on tablets for people who could come to the show. Of course, the gallery had to limit the number of people who came to see the show at different times. That’s been interesting. I would say that it’s felt very natural, since I am from the internet, so to speak. It’s felt very natural to work in this way, to do installations virtually, and to work with virtual sculpture by extension of that.

BL: Basically, you made the work in your studio in Rome; for the installation you had a lot of back-and-forth communication with the great team at bitforms and you pulled off a terrific show.

AH: I created simulations of what I wanted the installation to look like. I continue to do this for other shows that I’ve had. It’s been really interesting to discover how it’s possible to do all of these shows, and some online. The art of the online show has thrived in this time of pandemic, which has been a blessing of the pandemic, in some way, if there has to be a silver lining, it’s that there’s been a lot more thought into what an online exhibition can be, and how people can participate in exhibitions online, or virtually. What is a virtual space, what is the metaverse, this sort of thing coming back?

I think it is actually quite wonderful for artists to have this as an option, or for everyone to have this as an option. It’s not like you have to travel with your body, in order to go and see the artwork. The artwork can come where you are.

BL: But also, the artist could come.

AH: The artist can come to where you are. And I think this is important.

BL: You did these walkthroughs, so the viewer in the gallery walked through with the iPad or something.

AH: Yes. Exactly. This was one of the ways. And so, it was like a combination of people coming online, and meeting in Zoom with me, and then there were other people who were physically in the gallery space, but we all looked at the same work, and people who were purely digital could also view the AR as same as the people in the gallery, and it was just this notion of what an online show can be. It’s more than just JPEGs on a screen. It can be this real-time togetherness, real-time viewing of the work. Of course, the work has to lend itself to that, I think, but that’s what I do. So, it was perfect in some ways.

Barbara London: This was really a wonderful way to conclude. I think you are a master of your tools, and you’re just making great work.

AH: Thank you so much, Barbara. It means a lot.

BL: Thank you for sharing.

AH: My pleasure.

—

Support for Barbara London Calling 2.0 is generously provided by the Kramlich Art Foundation.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

The series is produced by Ryan Leahey, with production assistant Vuk Vuković. Web design by Vivian Selbo. Special thanks to Lee Ranaldo for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded August 2021; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Images & Video

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, entropy8Zuper.org. Website.

Auriea Harvey, Webcam Movies. 1999. Webcam Movies, 1999. Video (color, sound), CRT monitor, media player.

Auriea Harvey “Sketchbook Movies,” 1990–2012 – Excerpt.

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, The Godlove Museum. 2000-2007. Website, custom software (color, sound). 20 min 11 sec, loop.

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, The Endless Forest. 2005/2021-ongoing. Online game.